Why Buy Electric? (1900-1912)

The marketing for 1904 Pope-Waverley runabouts is early electric vehicle advertising in a nutshell; the car is “noiseless, clean, simple and safe,” exactly what its woman driver was assumed to want.

Looking back, it can often be hard to imagine why electric vehicles succeeded so well in the early automotive market. Not only were they expensive, slow, and short-ranging, but their batteries required constant maintenance. In 1900 steam cars dominated the North American motor vehicle market; electrics took second place with 38 per cent of the market share; and gasoline cars were a distant third. There are a few important reasons why.

Fashion

Simply put, electricity was fashionable in the early days of the 20th century. The world had been swept by the Second Industrial Revolution, as industry and commerce alike adopted the new technologies of electric lighting, telephones, radio, and the phonograph. Many major cities had well-established electric streetcar networks; electric cars were seen as the next logical step from the streetcar. Indeed, many early North American electrics were built around streetcar motors and batteries. Electricity was modern. Electricity was stylish.

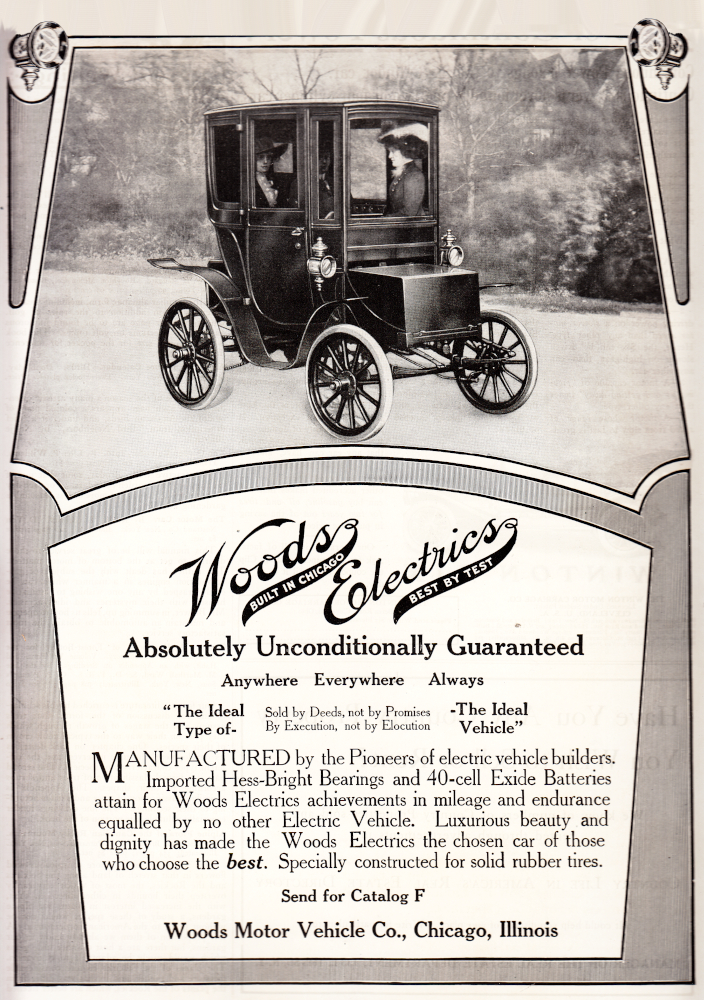

Woods Electrics, like this 1910 model built in Chicago, were advertised for their “luxurious beauty and dignity.” Electrics were not just vehicles; they were fashion items.

Hygiene

As large cities linked by horse-drawn carriages and steam-powered trains grew, so too did issues with cleanliness. City air had its soot, and city streets had their slush of wastewater and horse manure that could be knee deep on bad days. Unlike gasoline cars, which leaked oil and spewed smoke, or the slightly cleaner steam cars, electrics had no obvious emissions. Most still drew their power from coal power plants, but in an era before urban sprawl and environmentalism, this pollution was out of sight, and out of mind.

The vehicles of Columbia Electrics were aimed squarely at the ultra-rich, and the company’s ads, like this one from 1903, assumed that customers would need “the necessity of a separate driver,” or chauffeur.

Maintenance, sort of

Electrics had relatively few moving parts, a huge advantage for consumers who were still learning how to take care of their cars. There was no gearbox or transmission to keep oiled, no sparkplugs to change, nothing to become sooty or muddy. Battery maintenance was a great deal of work, and it was often compared to ministering to a sick patient rather than fixing a broken machine. In an era before home garages, most electric car owners paid to have their cars maintained and charged at large central garages.

Fuel and Charging

Before the invention of what we would now call the gas station (Canada’s first opened in 1907 in Vancouver), gasoline could only be purchased from drug stores (it was a common glass-cleaning chemical). Without any certainty that they would be able to find any gasoline on their trips here and there, drivers often had to lug around huge drums of spare gas. Although electrics suffered from much shorter ranges, they were usually being used in cities, where electrical sources were plentiful and garage charging stations easily accessible. Plus, current electricity was substantially less expensive than gasoline.

An inventive electrical eel / Built himself an automobile; / He needs no gasolene / compressed air, or steam, / He attaches his tail to the wheel.

-Charles Welsh, Automobilia, 1905

Starting

One of the great flaws of most early automobile designs was the starting process. Only electrics could be quickly started up and driven off; the process usually consisted of flipping a switch and stepping on a pedal or pulling a hand throttle. The competition, by contrast, was not quite so easy. Starting up a steam car was time-consuming; pressure had to build in the boiler, and could be difficult to achieve in bad weather. Starting gasoline cars was dangerous; they had to be cranked by hand, and an unaware driver starting a gas car improperly risked bruises, broken limbs – sometimes nicknamed “Ford fractures” – or worse.

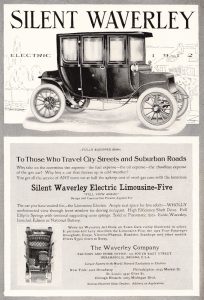

The comfort and luxury of a 1911 Waverley limousine came with a steep price tag; $3,500 U.S., roughly the cost of five contemporary Ford Model Ts.

Comfort

Everyone likes to drive in style and comfort, and electrics offered the most comfortable ride around. They were quiet – early New York cabs were nicknamed “Hummingbirds” because of their soft sound, with none of the hissing valves or rattling, roaring engines of steam or gas cars. On the move, electrics delivered power directly to their wheels, with no need to shift gears, so there was never any risk of stalling or being jostled by a novice driver in an electric.

All of these factors led to the popularity of the electric auto in the big cities. Private and business customers alike, eager to appear forward-thinking and get in on the ground floor of the next big thing, flocked to the electric vehicle, leading to a sudden growth in Canadian electric car companies.