The Gasoline Years, Part 1 (1920-1947)

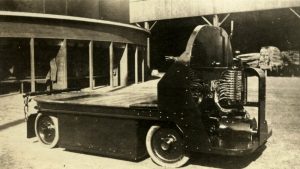

The new face of the electric vehicle in the 1930s: the industrial platform truck, or its close cousin, the electric forklift.

The dominance of the gasoline car did not mean an immediate end to the electric vehicle as a concept, and electrics would endure in some form or other for the next half-century, though never at the forefront of motoring. In North America, Detroit Electric was the last major dedicated electric vehicle manufacturer to cease production of passenger cars, selling refurbished older-model electrics with new bodies well into 1942.

Industrial vehicles – such as forklifts, mine trucks, and short-range delivery wagons – made up the vast majority of electrics still in use during this half-century of gasoline dominance. England would begin developing a huge fleet of electric “milk floats” for milk deliveries, for instance, but these were never intended as passenger vehicles. Electrics did find a home in several situations: when vehicles were needed to run without combustion, or to tow extremely heavy loads, or to operate inside factories where they could be constantly recharged. The few passenger electric vehicles developed in this period are true standouts, though none are of Canadian origin.

Rationing Revives the Electric

Peugeot’s compact VLV electric was unveiled in a surprise announcement in May 1941, and production and sales continued despite the German occupation of France.

Rising tensions and the subsequent outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 led to a small resurgence of the electric vehicle market around the world. Rationing of gasoline and the destruction of supply lines for engine parts and tires meant that small, short-ranged electrics suddenly had a practical use again.

David electric taxicabs being driven and recharged in Barcelona, Spain, circa 1939. (Captions available in both English and French). View this video with an English transcript.

Spain’s economy was left devastated by the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939. With oil imports heavily restricted, several car companies, including David of Barcelona, converted imported Opel and Citroën cars into electric taxicabs for many years. In occupied France, restrictions on gasoline car ownership prompted Peugeot to build 377 two-seater VLV electric cars between 1942 and 1945, although German forces prevented continued production of the vehicle.

Although slow and short-ranged, the inexpensive 1947 Tama worked as a truck, passenger car, or taxi, and was just what Japan’s recovering economy needed.

Japan saw its own postwar electric car boom, as the newly reformed Japanese government encouraged local manufacturers to build inexpensive electrics in response to heavily rationed gasoline and engine parts. One of the most prominent was the Tokyo Electric Automobile Co. Tama, built in 1947 by what would eventually become Nissan.

Germany’s Wartime “Hybrids”

Germany led the field in the realm of hybrid vehicles, though in an unexpected way. Ferdinand Porsche continued his work on hybrid gas-electric propulsion, culminating in the production of 91 of the Sd.Kfz. 184 Elefant, a 65-tonne self-propelled anti-tank gun most famously used at the Battle of Kursk in 1944. He would use a similar hybrid drive train in the two prototypes of the 190-tonne Maus, the heaviest tank ever built.

The end of rationing and the return of normal global trade after the end of the Second World War led to the full return of gasoline cars, with the electric consigned to obscurity. The concept did not totally die; in the 1950s and 1960s the technological developments of the Space Race would create a new interest in electric transport.