A.C. Leighton: Teaching at the Tech

A.C. Leighton’s life changed again in the very late 1929. When the head of the art department at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (now SAIT), Lars Haukaness, died suddenly on a solo painting trip near Lake Louise, Superintendent of the Tech, Dr. W.G. Carpenter, was tasked to find a replacement. He specifically sought the advice of artist, Reginald Llewellyn Harvey. A.C. had met R.L. Harvey during one of his previous trips to Canada and the two artists had enjoyed numerous sketching trips together, so Harvey suggested A.C. Leighton.

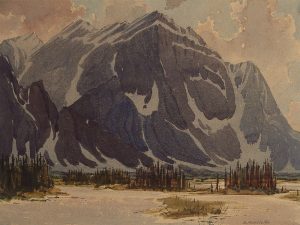

Upon the recommendation of Harvey, Dr. Carpenter wired A.C. in Montreal. At the time, A.C. was travelling with his exhibition of windmills and mountain paintings at T. Eaton Co. department stores across Canada. When Dr. Carpenter offered him the position as head of the Art Department at the Tech, A.C. resigned from the CPR and, rather than returning to England as he had planned, he headed to Calgary to take up his new position.

When he announced the appointment Dr. Carpenter said, “With Mr. Leighton at the head of its art department, the Institute of Technology and Art believes that it can contribute in a large way towards reducing the lack of appreciation for fine arts that is apparent among the greater mass of people in the west.”

A.C.’s first day of work was December 2, 1929. He was successful enough that A.C. returned to teach at the Tech permanently the next fall. The Albertan lauded the decision: “Mr. Leighton’s appointment points directly to the fact that a serious endeavor [sic] is being made to establish Calgary as a centre for the study of art in the northwest […] It marks the beginning and forms the nucleus for a standard of art found all too seldom in our centres of learning.”

It proved to be a wise appointment; A.C. began his role with five students and by 1931 there were 90 students in the art department. Obviously, he was instrumental in creating the art program at the Tech. His students Bernard Middleton and Margaret Staples (née Young), were the first to receive Fine Art Certificates there.

A.C. was an incredibly devoted and accomplished art teacher who kept himself busy with a full-time teaching schedule, offering day and evening classes at the Tech plus summer programs. He was so devoted to his student’s work that he would also become intertwined with their personal lives. If a student were struggling outside of school, A.C. would do everything he could to help them out. He gave his time and occasionally his own money to provide students every opportunity he could. Nights would find him at the Tech working with keen students. If they had the desire to stay in the studio, A.C. would most often remain. He also strived to procure outside funding for his students.

He was known to lecture on Art Appreciation to the Canadian Club to raise funds, and he would approach companies like T. Eaton Co. and the Hudson’s Bay Co. to secure scholarships for his students. “He bullied them into it,” said Bernard Middleton, one of A.C.’s most promising students, who received the T. Eaton Scholarship.

His teaching style was so effective, A.C. had a hand in developing and mentoring some of Alberta’s most celebrated artists. He taught with Henry G. Glyde and Nicholas de Grandmaison and mentored the next generation of Alberta artists, notably Marion Nicoll, Bernard Middleton, Margaret Shelton and Barbara Harvey, whom he would eventually marry.

Yet, this couldn’t last. Over time, A.C. began to feel the burden of teaching full time while trying to maintain his art career. Because of his workload, his health began to fail. Then, A.C. took a lengthy sabbatical in 1936 only to resign from his position at the Tech in 1938. Unfortunately, he never taught again.

“His success I suppose and his failure at, as a teacher is that he demanded the same dedication that he had for himself from everybody.”

—Barbara Leighton