A Waterway, a Way to Meet

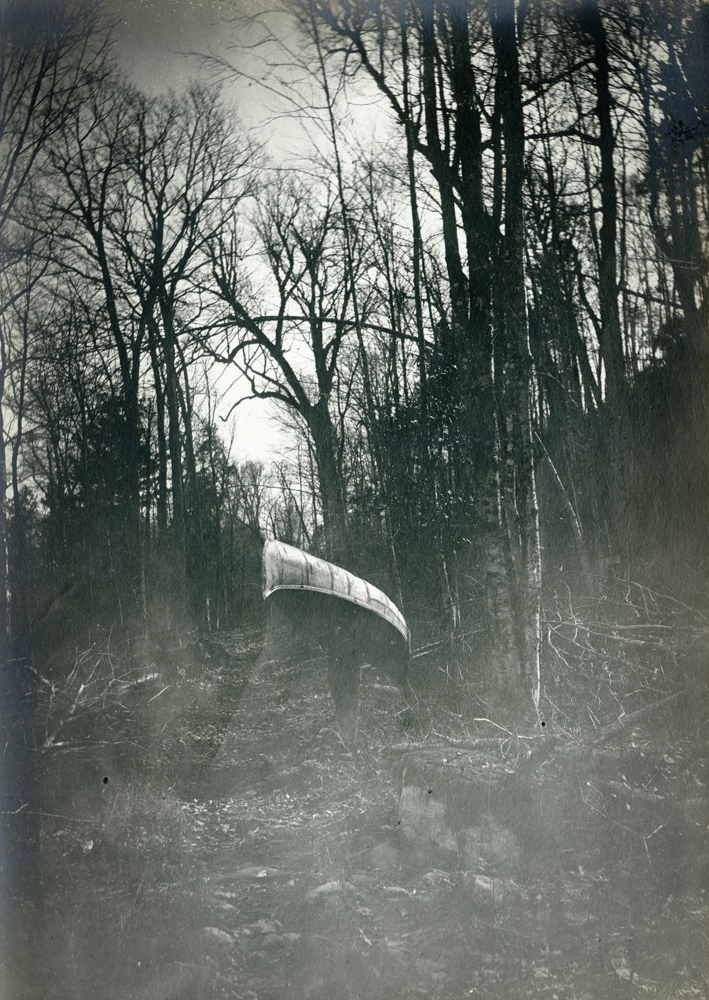

The loneliness of the portage,

A practice repeated for thousands of years,

An exhausting patience that has carved the bodies and souls of men,

With my spine broken by the canoe, I walk in the footsteps of unknown travellers,

Whose tracks will be lost in the wild grass over time, But the river will always remember.

Stéphane Rostin-Magnin

[Loose translation]

Like the first Atikamekw, let’s board our canoes and follow the ancestral transportation route that is the Saint-Maurice. By taking this water highway, long before the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century, we can come into contact and trade with the Anishinabeg (Algonquin) to the west, the Cree and Innu to the north, or the Iroquois, Huron-Wendat and Abenaki to the south.

Several sites along the river were used for trade between these Indigenous nations, including Metaperotin (Trois-Rivières), Wemotaci, Kokac (flooded when the Blanc Reservoir was created, upstream of the Rapide-Blanc rapids) and Oskisketak. The Atikamekw offered fish, meat and pelts in exchange for copper and corn.

They used the various resources of the Tapiskwan Sipi (Saint-Maurice River) to meet their own needs and for trading purposes. By procuring ash, which grew in areas further south, they were able to build stronger, more durable frames for their birchbark rabaskas.

The river strategically brought together the various Indigenous peoples who were allies in the war against the Iroquois in the 17th century. To avoid Iroquois war parties, the First Nations peoples of the Ottawa River watershed and the Great Lakes took this route down the Saint-Maurice to reach the St. Lawrence.

First Contacts

As we travel a little further ahead in time, we’ll see that it was on the river that the first Europeans began to cross paths with Indigenous people. The first written account of contact between Europeans and Atikamekw dates from 1636, when the Jesuit Paul Le Jeune reported seeing them north of Trois-Rivières.

In the second half of the 17th century, fearful of the diseases brought by the colonists, the Atikamekw abandoned the southern part of the Tapiskwan Sipi.

Adventurers occasionally followed them northward, but the first written record of a European in the Haute-Mauricie is the account of a journey made by the Jesuit superior of the Trois-Rivières mission, Jacques Buteux, in 1651. During his three-month stay, he noted that the Atikamekw already had rifles, swords, rosaries and flour, which showed that trade was not uncommon.

Adventurers, Travellers and Tourists

Our journey on the Saint-Maurice River has its share of dangers, with its many rapids and falls, which were challenges for fur traders, soldiers and travellers alike. Ironically, these same rapids and falls attracted many curious visitors from Canada, England and the United States in the 19th century. Large numbers came to admire the scenery along the Saint-Maurice, including Shawinigan Falls.

Many prominent people travelled to the area, such as civil engineer and scientist Sir Sanford Fleming in 1865, and various governors general of Canada, including Elgin, Head, Monk and Dufferin. It wasn’t until the 1870s, however, that surveyors and tourists ventured as far as the Haute-Mauricie, led by Atikamekw guides.