Building a Railway

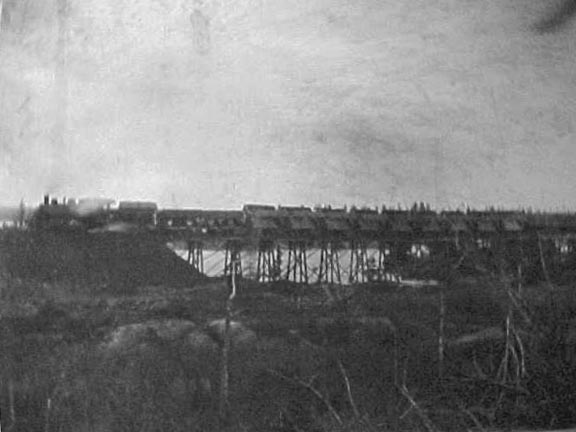

A train stops on its tracks to dump fill for the railway causeway being built over Cole Harbour, ca. 1916-17. Wilfred Bissett Album. CHRHS Archives.

Conditions in the salt marsh, however, didn’t return to the pre-dyked situation. Not long before the destruction of the dyke, a new venture across the harbour had begun. It was the time of railways and new lines were being added all around the province. A railway line was proposed to extend the existing line from Windsor Junction to Dartmouth, eastward to Musquodoboit Harbour, and then inland up the Musquodoboit Valley, to Upper Musquodoboit, and beyond. Plans to extend the line on to Guysborough were later abandoned. This railway link would be a boon to the people of Cole Harbour and points east. It would pass across the middle of the salt marsh over four wooden bridges where the major streams ran from the upper marsh. The biggest of these watercourses was the Little Salmon River which entered the marsh on the eastern side of Flying Point. The river can be seen today as it passes under the first, and widest, of the bridges on the Trans Canada Trail.

A steam shovel moves earth in the course of building the Eastern Railway. ca. 1916-1917. Wilfred Bissett Album. CHRHS Archives.

The building and operation of the railway is explored in the exhibits of the Musquodoboit Railway Museum, and the former rail bed has been reborn as the Trans Canada Trail. When the causeway across Cole Harbour was begun about 1915, Kuhn’s aboiteau gates were still holding back much of the water that would otherwise have flooded the salt marsh. After the gates were destroyed, the ocean began to reclaim the harbour. Rock had to be added to the rail bed, which was insufficient by itself to raise the track above flood tide levels. The bridges in the rail bed could not handle the outflow of water from the upper harbour, affecting the tidal exchange in the upper harbour. Over the years it has adjusted, as natural systems are wont to do.

A portion of the railroad crossing the salt marsh can be seen in the 1965 film The Railrodder, starring Buster Keaton, which is available to watch for free through the National Film Board of Canada. The early part of this film made in the 1960s takes the viewer from the Thames in London across the Atlantic to the shores of Lawrencetown, east of Cole Harbour, and follows the track of the old railway through the marshes and over the causeway that crossed the saltmarsh. It is a quick passage but gives a good overview of the marsh. The section begins at 1 minute, 15 seconds, and ends around 4 minutes, 15 seconds. The film plays music throughout, but no words are spoken.

Other changes were made to the entrance to the estuary: changes that have continued to affect the natural rhythms of the salt marsh. Destruction of the dyke severed the connection between West Lawrencetown and Cow Bay, because the bridge and aboiteau were no longer useable. At low tide, the fresh water from the saltmarsh roared through the gap left by the old aboiteau and the ocean roared back in with the rising tides. This gap was now the only entrance to the estuary and was deep and fast-flowing. Sand dunes gradually built up along the old eastern barrier beach and encroached westward across the mouth of the harbour. The sand and gravel came from the eroding drumlins which form the headlands outside the harbour and continued to build on either side of the deep channel. The available sand and gravel caught the attention of a construction company which purchased the land, including what was left of the barrier beach, a small, treed island on the marsh side of the beach, and the expanse of dune that was piling up on the ocean side. A bit of this property, on the inner side, was retained by the Dartmouth Rod and Gun Club.