A Slow Start to a Community

Recent Arrivals

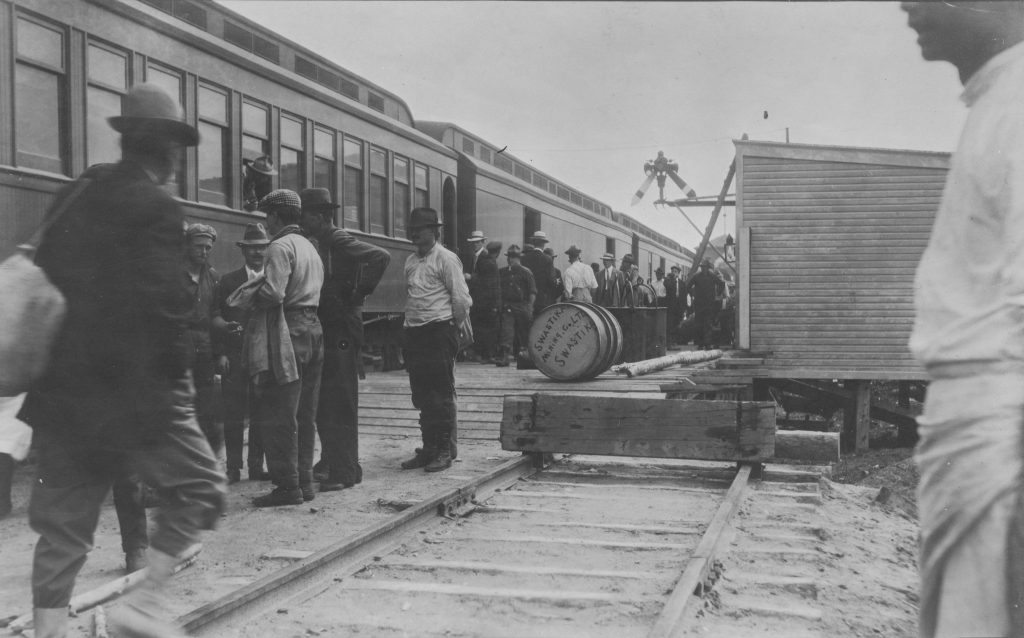

By 1910, rumours of more gold finds in the Kirkland Lake area led to prospectors arriving by the trainload in Swastika. The village named after the ancient good luck symbol had several short-lived mines of its own.

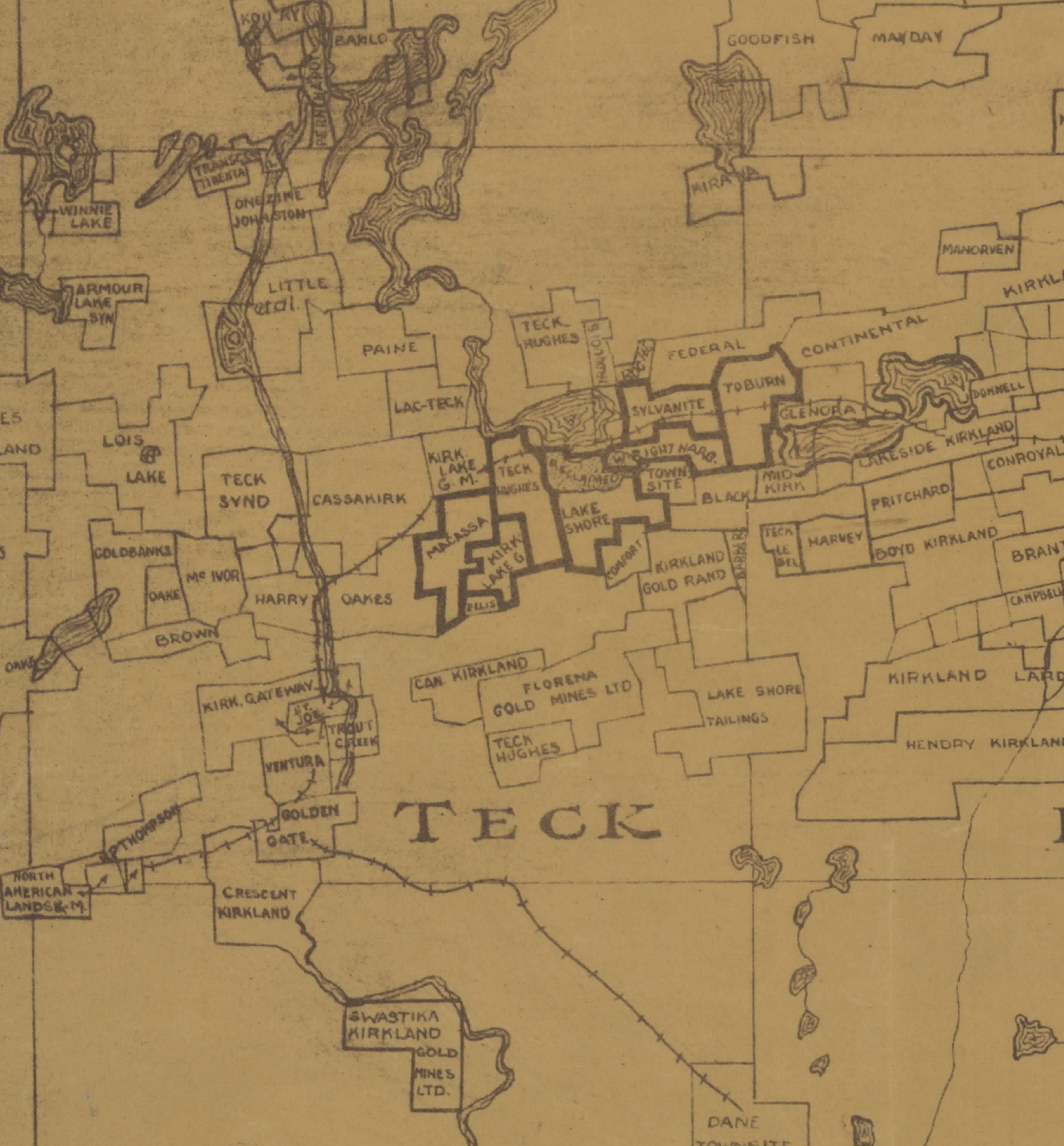

These prospectors were not only travelling north from the silver fields of Cobalt, but from across North America and beyond. They began to claim property that followed the path of an ancient gold-bearing geological fault known as the “Main Break”. This three-mile long stretch soon became the Kirkland Lake Gold Camp.

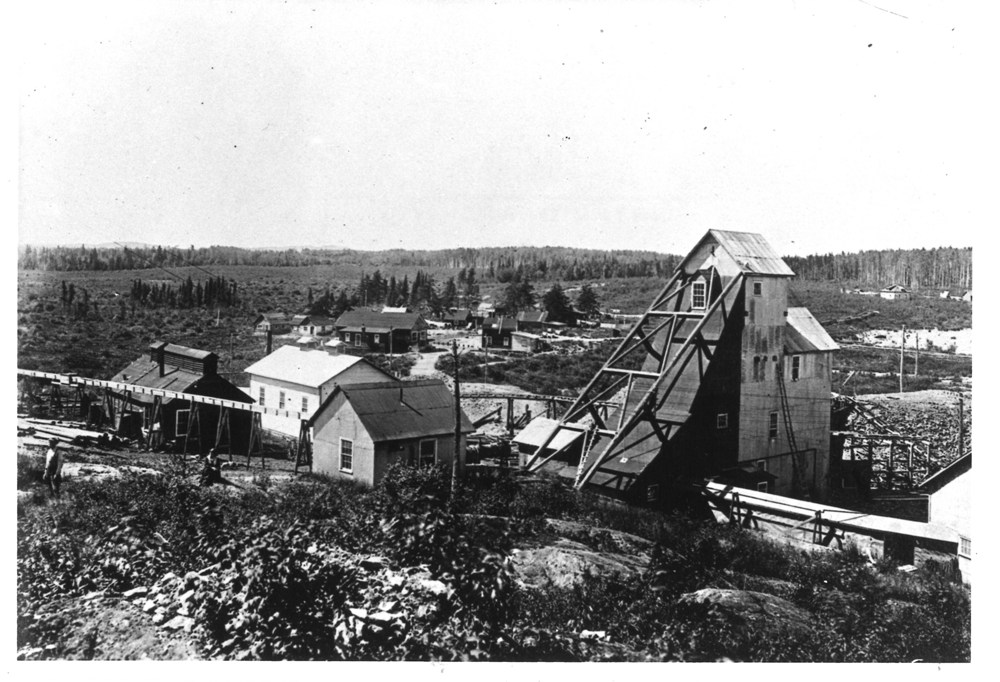

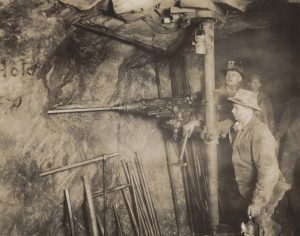

Finding a gold deposit was just the first step in starting a mine. Financial support from investors secured hired help and equipment. It took many hours of manual labour combined with machinery hauled to the still-forested site to hand-sink a vertical shaft into the hard rock of the Canadian Shield. It was hard work that wasn’t always rewarded with success, and many men left empty-handed.

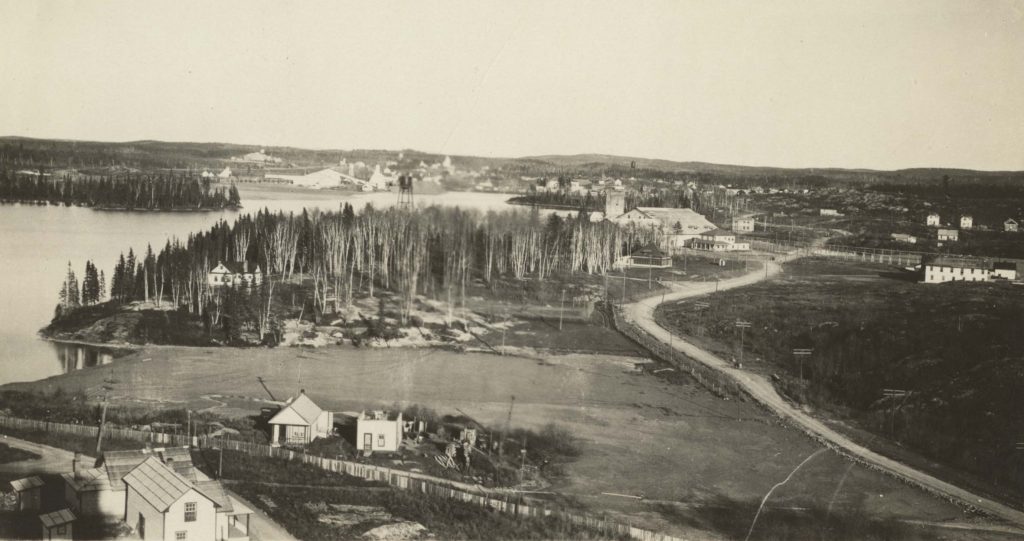

The Tough-Oakes Mine sank its first shaft in 1912, and the Sylvanite and Teck-Hughes Mines were in place the following year. At the time, Kirkland Lake was nothing more than a clearing in the bush with some tar paper-covered shacks and a few stores.

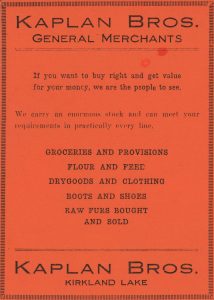

One of the early storeowners was Max Kaplan. He and his brother Hymen were Lithuanian-born Jewish immigrants who had originally arrived in New York, then Toronto, before making the move northward. They opened Kaplan Brothers General Store in 1915, and over the years saw Kirkland Lake develop from a rough mining camp to a modern town. And what was Max’s first impression of Kirkland Lake when he arrived?

“I felt like taking the train back to Toronto. I was terribly disappointed…there were a few log shacks and cabins but most of the settlement was on the Teck-Hughes property.”

But he was determined to stay on. The local Indigenous people traded furs and lumber to the Kaplans for supplies, while prospectors and early miners bought what they needed – sometimes on extended credit. The family business became a success, and the Kaplans made the new town their home.

The Kirkland Lake Gold Camp

The community did not see the same speed of development or population explosion as the boom town of Cobalt in its early years. The Gold Camp population was about 200 people in 1914, and except for a few families, it was mostly made up of young single men from the Maritimes and Ontario.

Some of these men left soon after to try their luck in other well-known northern mining towns like Sudbury and the Porcupine Gold Camp, or to join the Canadian military for the Great War. In both cases, many of these men never returned to Kirkland Lake.

The Lake Shore Mine and Wright-Hargreaves Mine were incorporated despite the setback of war and a labour shortage.

They would go on to be the largest gold-producing mines and employers in the Gold Camp.

A look at the payroll ledgers from these mines show mostly British surnames in the early years, with Eastern European names added by the late 1920s.

Mine management and supervisory positions were often held by British or Canadian-born men while recent migrants filled the more physically demanding and lower paid positions. They may have known little English, but they had a reputation for being hard-workers who were ready to provide the labour needed to get the job done.

While their wages were decent by Canadian standards, they were considered much better than those they would have received back home. For this reason, some migrants returned several times to the area on contract work, while others chose to settle permanently in Kirkland Lake.

The T&NO brought a wide variety of people to the area for more than just farming and the harvesting of natural resources. Optimism and opportunity were enough of a draw for those already in Canada, and those willing to travel from beyond Canada’s borders.