Post-War: Language and Culture

It was an easier transition for those moving from European countries to Kirkland Lake, as many of these cultures already had a presence in the community from the previous generation of settlers of the 1920s and ‘30s. This included social clubs and halls, churches, and a shared language to help the new Canadians adapt.

English as a second language was taught to working adults as an evening class at the local high school. Children, always adaptable, learned their adoptive language as much in the street with friends and in movie theatres as they did in school.

Stay-at-home wives were sometimes at a disadvantage when it came to learning English. Unlike their husbands and children, they were not always in regular contact with others who spoke the local language.

Tradition and Adaptation

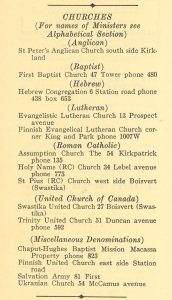

The church groups, synagogue, and clubs established by the earlier generation helped new immigrants, but also preserved their language and cultural traditions to the children growing up in Kirkland Lake.

This second generation of children mostly spoke English, and learned the language and customs of their parents at home or in special after-school classes.

As one person spoke about their experience of growing up in Kirkland Lake in the late 1950s:

“At times it was difficult finding someone to play with after school because many of my friends had to attend cultural classes set up by their parents.

For example, on Mondays and Wednesdays my Ukrainian friends would be in the Ukrainian Church basement taking Ukrainian lessons. On Tuesdays and Thursdays my Polish friends were at the Polish Church getting their lessons, learning their language and customs. Also the same type of thing was occurring with my Finnish, French, Italian and Jewish friends.

Kirkland Lake was almost similar to Toronto where they have their neighbourhoods such as Greektown, Chinatown, etc., but here in Kirkland Lake it wasn’t whole neighbourhoods it was streets.

A lot of the Italian kids lived on McKelvie Street, French kids lived on Hudson Bay Avenue, and Polish kids lived on Woods Street. You know what I mean. People would always gravitate to where people speak your own language and understand you, that’s how it was for a small town. For a small town, it was like living in a little United Nations.”

A Kirkland Lake Lifestyle

These cultural lessons would continue into the 1960s and were one way parents encouraged their children to embrace their heritage while integrating to a “Canadian lifestyle”. The definition of this Canadian lifestyle has changed over the decades, but is usually a combination of British and French settler values, with a strong dose of American influence, and unique elements from other peoples.

The “Kirkland Lake lifestyle” may have been based on this idea at the town’s start, but as the town grew over the decades, it became a distinct blend of melting pot and multiculturalism, all with a distinct Northern Ontario touch.

Vivien Spiegelman’s experiences in Kirkland Lake and the local high school of Kirkland Lake Collegiate and Vocational Institute (KLCVI) shaped her views:

“I think we invented multiculturalism in Kirkland Lake. For those of us who grew up in the immediate post-war period and who came of age in the late ‘50s, there was a healthy curiosity about the multitude of religious practices that percolated in K.L. and the never ending variety of ethnic backgrounds that we experienced, mainly through our stomachs.

Perhaps our parents harboured prejudice, but within the confines of [KLCVI] there was no room for such discrimination. The superficialities of where and whom you had been born were immaterial. What really mattered were character and what kind of friend you were.”

Vivien believed that many of her generation preferred the concept of the “inclusionary ‘melting pot’ because that’s the kind of environment we grew up in and one in which we felt very ‘Canadian.’”

This casual acceptance of diversity and not letting it affect how student interacted with student, or even neighbor with neighbor, was considered by many to be the norm across the community.

This way of thinking was in keeping with the times. The 1960s was a period of social change far beyond Kirkland Lake’s borders, but the impact it had on the inhabitants was probably felt most strongly by the youth. Some of these children and teens were recent immigrants who came to Canada with their parents, but many were 2nd generation Canadians.