The Push for “New Ontario”

The community of Kirkland Lake has seen its fair share of ups and downs over the last one hundred years.

Like many mining towns, Kirkland Lake’s economy has always depended on how long the mines could stay open and the value of the mineral being mined. With outside forces dictating the worth of gold, it affected gold mining and production, as well as the number of people the mines could hire. With the growth and decline of the value of gold, so too did the population of miners and their families in the town.

But before we can look at the story of why people from many backgrounds came to make Kirkland Lake home, it is important to look at how and why the town itself got its start. And this takes us to the early 1900s.

The Potential of Northern Ontario

At the beginning of the 20th century, Northeastern Ontario was still thought of as a remote area of boreal forests, lakes, muskeg and black flies.

While this still holds true, this was also when the resource-driven economy of the North began to develop at a fever pitch.

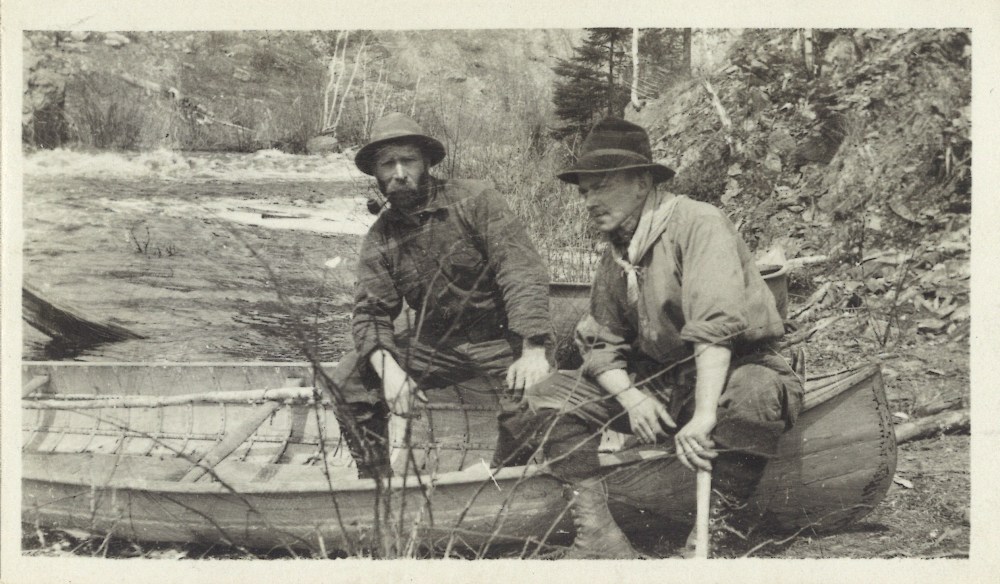

The region was already home to the Algonquin, Ojibwe, and Cree peoples. The population of First Nations, Metis, and recent settlers was small and spread out across a large tract of land.

Their livelihoods of hunting, small-scale agriculture, and the harvesting of furs and lumber continued to provide wealth for the provincial economy.

But the Ontario Government at the time wanted a push northward to settle the land and increase its agricultural productivity. With only rivers and rough trails providing access to the region, a reliable railway line needed to be built.

What would become known as a colonization train would open up the area and bring migrants to “New Ontario”. These newcomers would clear the land for farming, and in turn would ship additional produce and livestock south. A reliable form of transportation meant the sustainability of the entire region and the expansion of the Ontario economy.

Many of these newcomers left their homes in Southern Ontario based on the glowing reviews of friends and family who made the move north years earlier when the journey had to be made by steamship.

These settlers and early farmers were primarily of English and Scottish heritage, and when the call came to support the goals of the Ontario Government (and British Empire), they did so.

The government’s aggressive ad campaign to promote New Ontario also targeted those outside of the country. Pamphlets were sent to countries like Estonia, Finland, Norway and Sweden as it was believed that Northern Europeans were accustomed to cold climates and would thrive in Northern Ontario.

What the provincial government didn’t realize at the time was how much of a windfall to the economy just the building of the railway would unintentionally create.