Flying Blind: Learning on the Link Trainer

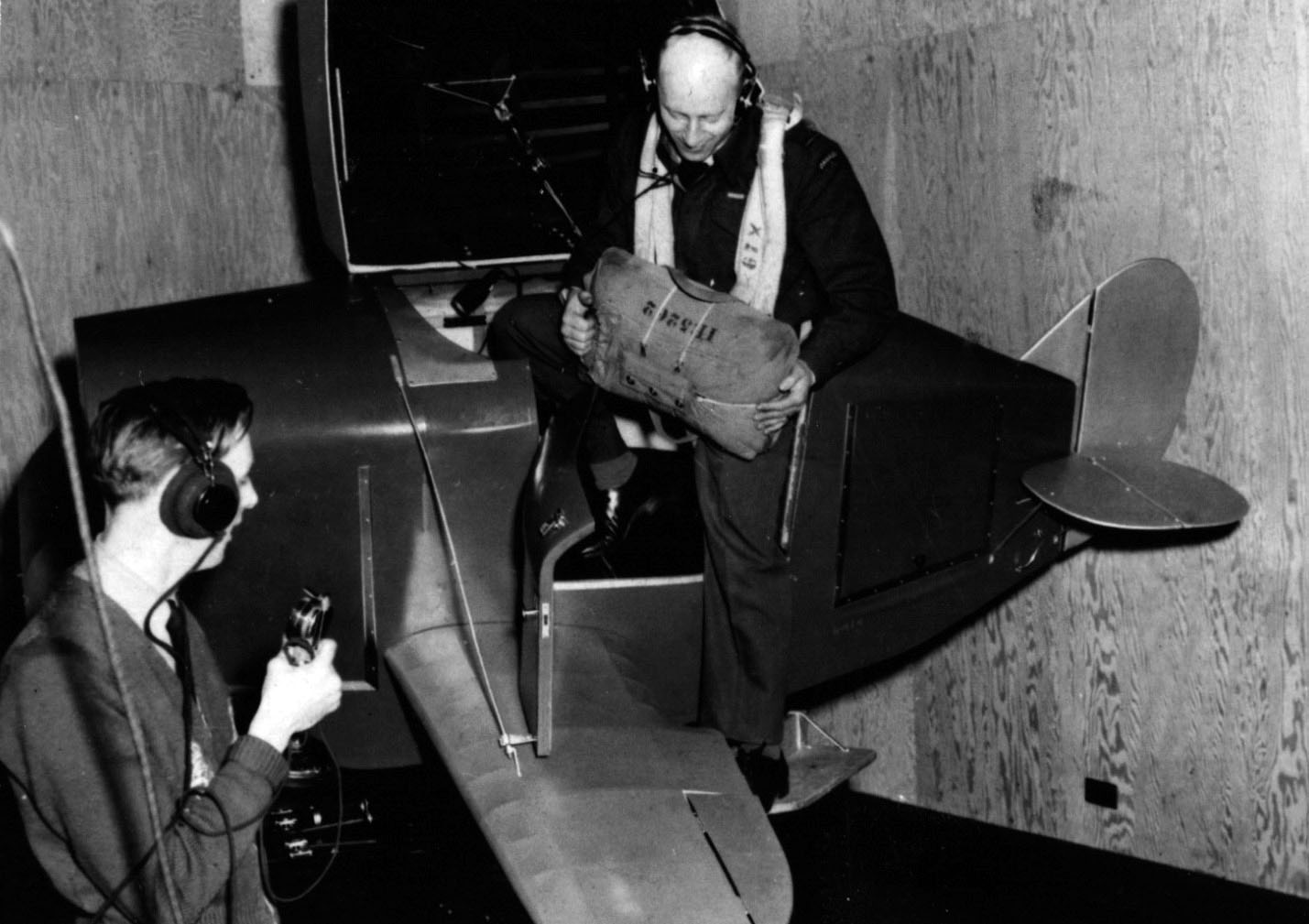

Here, F/O J P Smith “bails out” of the Link trainer for a photo in the “Windy Wings” on-base publication.

By the time recruits arrived at the Claresholm airbase, they had basic flight training and some experience in the air. However, flying at night or in poor visibility was a more advanced skill most had not yet acquired.

While technology in aviation was rapidly advancing, flying in these conditions was still very challenging in friendly territory, let alone in the skies over enemy territory under attack.

Pilots needed a safe way to learn to navigate in dark skies and under adverse weather conditions. A flight simulator called the Link trainer was adopted to teach instrument or “blind” flying techniques safely on the ground.

The Advent of the Flight Simulator

Edwin Albert Link invented the Link trainer in Binghampton, NY in the late 1920s. Link’s inspiration for the trainer came from his own desire to learn to fly.

Flying lessons were expensive and potentially dangerous. Link wanted to develop a way for students to get a feel for flying on the ground, long before they took to the air.

Using materials and knowledge he acquired working in his father’s organ and piano manufacturing facility, Link created his first flight simulator in 1928.

The first rudimentary training unit was based on a series of compressed air-driven organ parts and a motor to move the stationary “plane” up and down, right and left. It was just like flying in a real airplane!

Link received the patent for his invention in 1931. The Link trainer wasn’t officially adopted into a military flight training program until 1934, when the American Army Air Corp purchased six Link trainers. The following year, the Japanese Imperial Navy purchased Link trainers to train their pilots.

The start of WWII in 1939 propelled the Link trainer to become the go-to flight simulator to train airforce pilots. By the end of the war, over 35 countries had used the Link flight simulator, training over 500,000 pilots worldwide.

This included all the pilots in the British Commonwealth Air Training Program in Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom.

Learning in the Link Trainer

The Link trainer was used to teach instrument and “blind” flying techniques in the safety of a hangar. These “pilot makers” allowed pilots to simulate take-off, flight, navigation, descent and landing in darkness or low visibility, using only cockpit instruments.

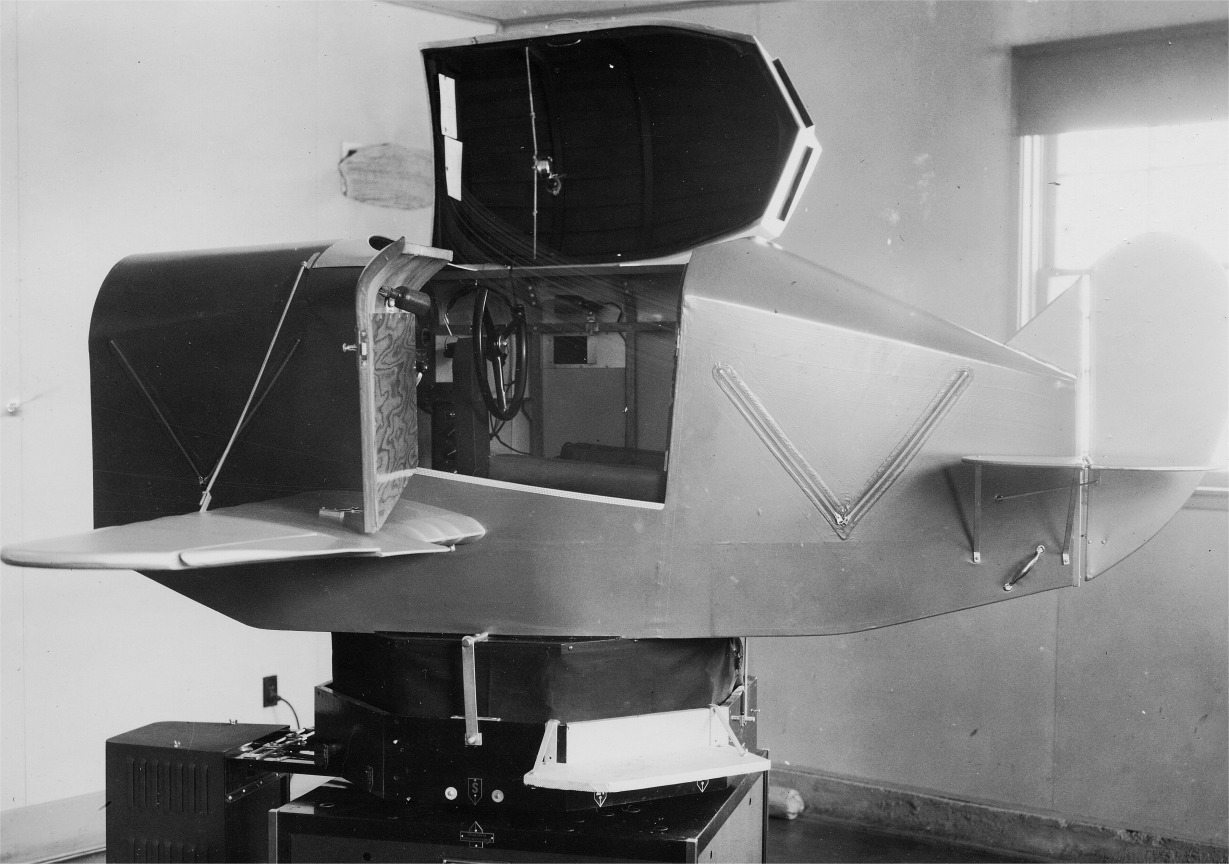

The small model “plane” was constructed of wood and canvas. It was bolted to a pedestal on the floor for stability. The cockpit of the trainer contained all the instrumentation, levers, controls and pedals in a full-sized training airplane.

The pilot was completely reliant on the instrument panel in the mock-cockpit – flying blind.

The flight instructor, seated next to the unit, would issue instructions to the trainee through a radio unit in the trainer. The instructor could also create “turbulence” and other flight conditions from his control station, including diving and evasive maneuvers.

The Link trainer would move up, down, left and right, controlled by the trainee through the unit’s control stick, levers and rudder pedals – and had a full 360-degree range of motion.

A mechanical “crab” recorded each training session. This allowed the pilot trainee to review each training session. This reinforced instruction, allowing for improvement in the next training session.

Pilot training included up to 100 hours of active flying hours before they graduated and “earned their wings.”

Once instructors were confident the trainee was ready, they would approve them for active flying in a variety of flying conditions. This included night and low visibility weather events, as well as the strong winds the region is known for.