Remembering Littlejohn’s Forge, Coley’s Point

Aside from providing heat for houses, coal from the Avalon Coal Shed provided fuel for local blacksmiths. The first blacksmith in Coley’s Point was said to be George Henry Jackson, but he was later joined by other blacksmiths and wheelwrights. Carts from the coal shed were backed into the local forges, unloading coal through a hatch in the forge wall into the interior coal pound.

The Littlejohn’s of Coley’s Point were one such family of local blacksmiths. The first Littlejohn to arrive in Newfoundland was William H. Littlejohn. He was born circa 1795, and originally came from Ipplepen, a small settlement in Devonshire, in the west of England. In the early 1800s, he arrived in the Port de Grave area on a ship owned by Newman & Roope, a business based out of Dartmouth, England.

Littlejohn was married on May 14, 1836 to Elizabeth Sealey and had three known sons: John Edward born October 17, 1836; William born circa 1837; and Thomas born February 22, 1842. At some point, the Littlejohns purchased land near Long Beach in Coley’s Point from William “Uncle Billy” North, who had settled there in 1810.

The third William in the family line, William Henry, was born in 1863. The forge he built would continue to operate into the 1970s. Bill Littlejohn, still living in Coley’s Point, is William Henry’s grandson. Bill was born in 1937, and his father was the last to run the forge, and had learned the trade from his own father. An only child, Bill grew up living with his grandfather and step-grandmother, and he remembers his grandfather as a talkative man, always telling stories about the way life was when he was young.

Horseshoes were the forge’s main trade, and wintertime was its most lucrative season, as all the horses in the area had to be shod for the winter’s work of hauling firewood from the woods. Frozen ponds being slippery, the horses needed winter shoes to stick on the ice.

“You’d hear the horse’s bells before daylight,” Bill recalls. “It was a first-come, first-serve basis. You’d hear the horses and the bells, and the men shouting at their horses. I can remember waking up in the morning to noises like that.”

Bill’s father woke at 6 a.m., and began work at 7 a.m. shoeing horses. There was no rest in the evening, however, as that was when he would make the shoes needed for the next day.

In the evening, the forge became a social area. All the men would gather at the forge, and help pump the bellows to keep the fire going. As they helped, they would tell yarns and brag about their horses. The shop was a place where local stories were kept alive.

When not making horseshoes, the Littlejohns also made bands for cart wheels, runners for slides and catamarans, grapnels for fishermen, and picks and shovels.

“With the coming of the pickup truck, horses weren’t needed like they used to be,” says Bill. “Then work shifted to working on the wholesale trucks, making U-bolts for attaching wood to the chassis. He used to do all that kind of work.”

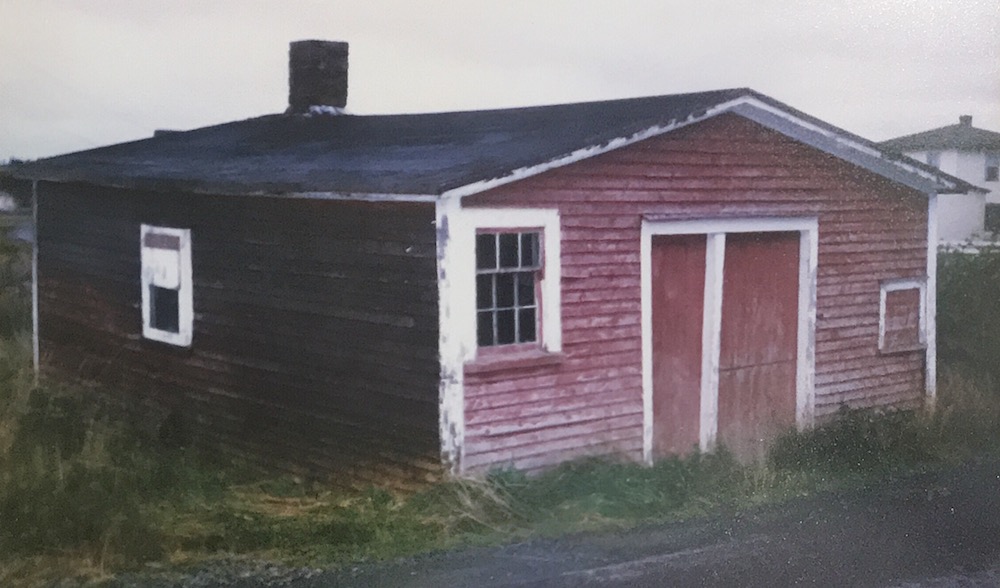

The day came, however, when the fire went out for good, and the ringing anvil fell silent. The forge lay unused for a time, until it came to the attention of the Bay Roberts Heritage Society.

The Society was founded in 1989, and spearheaded efforts to restore the historic Cable Building, which now houses the Road to Yesterday Museum, art gallery, and archives. As part of its work to preserve local history, the Society had the original forge operated by Bill’s father and grandfather dismantled. It was then rebuilt, piece by piece, inside the museum, including the hob, coal, and original ashes. In this way, the legacy of William H. Littlejohn and his family lives on.