Rebellion

The Red River Resistance led by the Métis was sparked in 1869 by the Hudson’s Bay Company decision to surrender Rupert’s Land to the newly formed Dominion of Canada with little regard for the people who lived there. The Métis of the Red River Colony were concerned about culture and land title and with no assurances of their rights, feared losing their farms and livelihoods. As government surveyors began to assess their settlements according to an English-Canadian system, the Red River Métis under the leadership of Louis Riel rebelled and formed their own provisional government to negotiate terms for entering Confederation. The events of the Red River Resistance led to the creation of the Province of Manitoba in 1870.

A second Métis resistance in 1885, the Northwest Rebellion, grew out of similar frustrations regarding land, language and religious rights in the District of Saskatchewan. They drew the support of Cree and Blackfoot nations and others whose communities were suffering because of the decline of the bison. Led again by Riel, the Métis and several First Nations went to war against the Canadian government. But they were unsuccessful in their fight and Louis Riel surrendered on May 15, 1885, during the Battle of Batoche. On November 16, he was hanged for treason.

Olivia Marie Golosky speaks about Louis Riel, with transcription.

Belle was in her second year at Wesleyan Ladies College in Ontario when the Red River Resistance began. She was likely exposed to anti-Métis sentiment but was protected from being a target of it herself because of her family’s ties to the Canadian government.

Belle’s aunt, Isabella Sophia Hardisty Smith, was married to Donald Alexander Smith who played a crucial role in the negotiations between Canada and Louis Riel. On December 10, 1869, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald sent Smith to bargain with the leaders at Red River by offering employment and money to those who would cooperate with the government. Smith commandeered Belle’s uncle, Richard Charles Hardisty, to join him on the mission and saw Richard Charles held at Fort Garry by Riel. He was released shortly after as Smith continued negotiating with the Métis. Smith met directly with Riel on several occasions including during the winter of 1870 when Riel was considering hanging Thomas Scott, a government surveyor. Smith and Hardisty left Fort Garry on March 19, 1870, two weeks after Scott was executed.

In 1885, a year after Belle and James were married, her brother, Richard Robert “Dick” Hardisty returned to Canada having served with the British army on the Nile Expedition of 1884. He was promptly sent to battle as a private in the Canadian army. He fought at the Battle of Fish Creek in April then the Battle of Batoche in May. Dick was killed in action on May 12 by a gunshot wound to the head. The Winnipeg Daily Sun reported on his death and noted “there [was] general regret in the camp, Dick being a favourite.”[1] He was described as “the life of his friends.”[2] He was laid to rest in Winnipeg on May 24 and Belle and her family presumably attended the funeral. It drew a gathering so large, its size was “never before seen in Winnipeg or the North West.”[3]

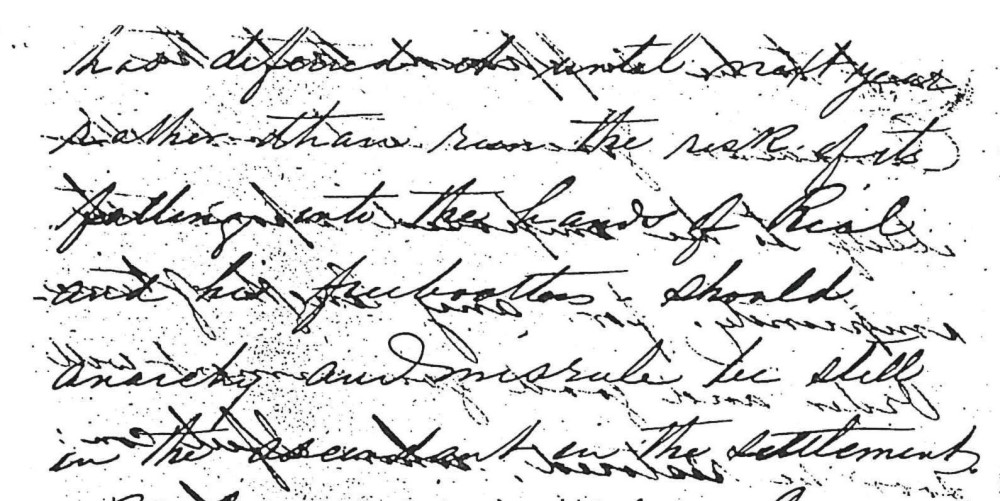

Belle did not comment publicly on the Northwest Rebellion or the Battle of Batoche despite her family’s involvement with the Canadian government. Discretion in responding to political affairs was necessary in her new role as James’s wife. However, in 2001, Belle’s grandson, Donald Lougheed, revealed to the Calgary Herald that she spoke of the rebellions in private.

“She told me about her brother who was killed at Batoche… I remember her talking about Riel… She would have been terribly upset with all this talk of Riel today.”[4]

The Métis rebellions affected Belle not only because one of them claimed the life of her brother but also because they may have intensified the conflict within her which pitted her sense of identity against her desire to meet society’s expectations of her.

[1] George Flinn, Winnipeg Daily Sun, May 14, 1885, p. 1

[2] As cited in: Doris Jeanne Mackinnon, Métis Pioneers, University of Alberta Press, 2018, p. 66

[3] Doris Jeanne Mackinnon, Métis Pioneers, University of Alberta Press, 2018, p. 66

[4] “A Daughter of the West Who Made a Difference,” Calgary Herald, December 30, 2001