A Proper Education

William Lucas Hardisty wanted his children to receive a European-style education but he was also keen that his wife, Mary Anne, attend school, too. Soon after their marriage, he expressed the idea in a letter to his brother-in-law, Joseph McPherson.

“I was up at Fort Simpson in August and got married there in a very offhand way to a Miss Allen—she is an orphan, her parents having died when she was an infant—her education has been very much neglected, and it is my intention to send her to school for a year or two. It is a very unusual thing to send a wife to school and no doubt will cause a laugh at my expense, but I don’t care a fig and won’t mind the expense, so long as she is enabled thereby to act her part with credit in the society among which she is placed.”[1]

Mary Anne never did go away to school but the expectation of HBC men and their families to adhere to European customs and ideals was real and specifically applied to men whose wives were Indigenous. This unfortunately contributed to the incorrect idea that Métis people exist on a spectrum of whiteness and Indigeneity, an idea reinforced by notions of the necessity of a European education.

“One of their tenets was that if mixed-blood daughters were to mature properly, it was necessary to minimize maternal influences. Thus, Red River reversed the British trend of mothers inculcating moral values in young children, as well-intentioned fathers with Native wives involved themselves in the early religious education of their daughters. British style schools took over where fathers left off… [T]he most powerful moulding force in the elevation of girls in Red River was Matilda Davis, herself a daughter of the country… Her HBC officer father, John Davis sent her to England to be educated. When she returned to establish a school in the Red River parish of St. Andrew’s in about 1840, she brought with her solid middle-class values.”[2]

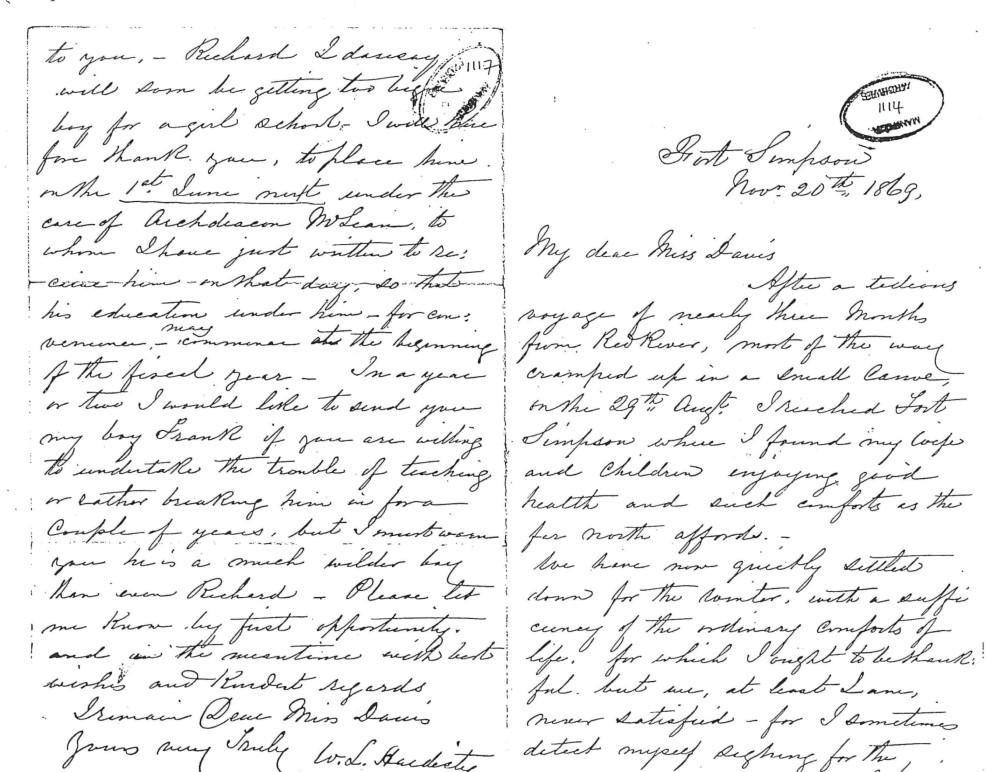

William Lucas’s attitudes toward education are evident in a letter he wrote to Matilda Davis about his children’s prospects. His comments also partly explain why he chose not to send them to Sacred Heart Residential School in nearby Fort Providence which had opened in 1867 and was admitting Indigenous children from all over the Mackenzie District.

“It is very difficult in this District to keep the children away from the Indians who are always about the house and my children labour under the further disadvantage that their Mother has no education. I am generally absent from them all winter, so that they are to be pitied more than blamed for their mischievous habits. I hope therefore that you will excuse them in they are not so good or so well behaved as those who have educated Mothers to instill virtuous habits into them from their infancy.”[3]

When Belle was about six years old, she was sent to Matilda Davis’s school just north of Winnipeg. But after only a few months, she fell ill and was sent from there to live with her grandmother, the Métis wife of HBC chief factor Richard Hardisty Sr., Marguerite Sutherland Hardisty, in Lachine, Quebec. In 1869 when she was eight years old, she was sent to Wesleyan Ladies College in Hamilton, Ontario, even though William Lucas did not consider it the ideal institution for his daughter, either. The following year, he wrote to Matilda Davis about “little Bella’s” removal from her Winnipeg school.

“[It] was solely on account of her health as my object in placing her at your school is that she might be instructed…where she was so well cared for and where her progress, in spite of her illness was so much greater than any place since… [I]n fact she has gone back in everything.”[4]

Belle may not have been happy at Wesleyan Ladies College as she was considered different from her peers. One classmate later recalled that Belle had been described as the daughter of an Indian chief. That incorrect assumption may have arisen from her father’s position in the HBC as chief factor or it may have had to do with her indigeneity but either way, it shows that Belle was perceived as “other.”[5]

Belle did not graduate from her program and finally left the school in Hamilton in 1875. She returned to the North where she lived with her parents until her father retired in 1878. After that, she lived with various relatives including her uncle and aunt in Winnipeg, Donald Alexander Smith and Isabella Sophia Hardisty Smith, who would become Lord and Lady Strathcona in 1897. Belle’s time with these influential people undoubtedly contributed to her understanding of the deportment and manners expected of those in the upper levels of society. After Belle’s father died in 1881 and her mother married Edwin Stuart Thomas in 1882, Belle went to Calgary to live with her aunt and uncle, Eliza MacDougall Hardisty and Richard Charles Hardisty who would become Senator Hardisty in 1888.

Lawrence Gervais speaks about Belle’s connection to Miss Davis’s school, with transcription.

[1] Letter from William Hardisty to his brother-in-law Joseph McPherson, November 1, 1857, Glenbow Archives, Patrick/McPherson Family fonds, M-941-1

[2] Erica Smith, “Gentlemen, This is No Ordinary Trial” in Reading Beyond Words: Contexts for Native History, ed.Jennifer S.H. Brown and Elizabeth Vibert,2003, p 364-80

[3] Letter from William Hardisty to Miss Davis, Nov 20, 1869, Lougheed House Conservation Society, Don Smith fonds

[4] Letter from William Hardisty to Miss Davis, July 10, 1870, Lougheed House Conservation Society, Don Smith fonds

[5] Doris Jeanne Mackinnon, Métis Pioneers, University of Alberta Press, 2018, p. 64