Identity

From childhood, Belle was encouraged by her father, her school-teachers and others to adopt a Eurocentric way of life and separate herself from her Métis heritage. Presenting herself as a white person allowed her to navigate the tense and complicated divisions between the First Nations, Métis and European settlers with ease despite her physical appearance as Indigenous. In order to thrive in Calgary, it was crucial for Belle to identify as British, a strategy adopted by many Métis people of the time. In 1911, the Albertan published an article disparaging Indigenous people and other people of color.

“[The province] does not want a coloured Alberta… Close out the yellow man, the red man and the black man. They are not good settlers. They cannot become good Canadians.”[1]

But Belle did not let such comments offend her deeply.

“[Her] love of life was too great to allow racial slurs to hurt her… She had the luxury of being exactly who she wanted to be; after all, who in early twentieth century British Calgary stood higher on the social pyramid than she?” [2]

Belle experienced discrimination because of people’s responses to her Indigenous ancestry specifically and to indigeneity in general but at the same time, she enjoyed a life of privilege and was held in high regard by everyone. Even at Wesleyan Ladies College when she was referred to as the daughter of an Indian chief, she was distinguished as someone with elevated social standing. Her relationships with her father, her husband, her uncle, Richard Charles, and her aunt and uncle, Isabella Sophia and Donald Alexander, helped cushion her experiences as a Métis woman. James was taunted and criticized for “marrying an Indian” despite the normalcy of such marriages at the time and the place he and Belle occupied among the elite, yet he continued to support Métis interests.[3] He demonstrated this by handling the legal matters related to Mary Anne Allen Hardisty Thomas’s scrip applications in 1901.

After she left home, Belle did not stay close to her mother, Mary Anne. There is little evidence of correspondence between them after William Lucas died in 1881 and Belle is not mentioned in her mother’s obituary. A considerable distance separated them with Belle in Calgary and Mary Anne in the District of Dauphin, Manitoba, but Belle’s brothers seemed to have kept in touch with their uncle, Richard Charles, despite there being similar distances between them and him. But even without her mother’s influence, Belle carried parts of her Métis upbringing into her adulthood. She danced the Red River jig on a few occasions, a dance many feared would become extinct in the face of colonization. And Belle owned a few hand-beaded items like purses and articles of clothing although it is not known whether she did any beading herself.

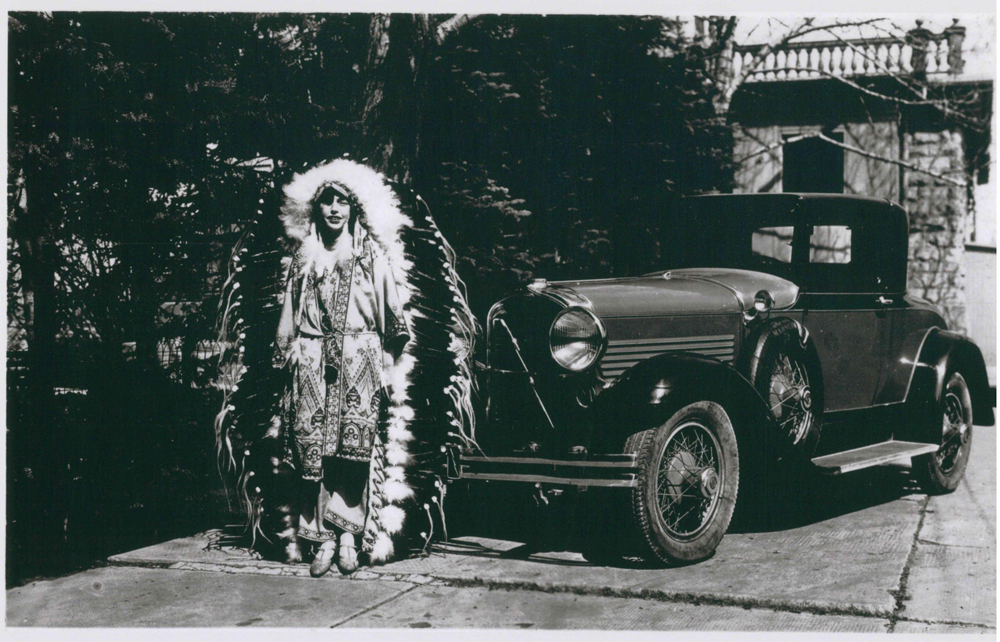

Southern Alberta Pioneer and Oldtimers women’s group at Lougheed house, Calgary, Alberta, July 1923. Photograph by W.J. Oliver. Glenbow Archives ND-8-408.

Despite her own Métis ancestry, Belle was prejudiced against other Indigenous people. Likewise, Belle’s father was vocal about his disdain for other Indigenous people throughout his life and career. Belle lived in a society that was aggressively trying to erase Indigenous identities and constantly compelling her to distance herself from her Métis culture. She was displeased to have “squaws and half-breed women” as servants in her early days in Calgary.

“[T]hey could wash but could not iron, and they were never dependable.”[4]

Her estimation of Métis people and the Métis cause was further diminished when her brother, Dick, was killed by Louis Riel’s men in the Battle of Batoche in 1885.

Belle understood that to succeed in the role of wife of a prominent lawyer and later, as Lady Lougheed, she needed to be perceived as non-Indigenous. Like many Métis people of the time across Canada, Belle’s indigeneity became invisible as Anglo-domination flourished.

[1] “Keep the Negroes Out”, The Albertan, April 6, 1911, as cited in: Donald Smith, Calgary’s Grand Story, 2005, p. 56

[2] Donald Smith, Calgary’s Grand Story, 2005, p. 61

[3] Alan Hustak, Peter Lougheed, McClelland and Stewart Ltd, Toronto, Canada, 1979: “In the homogeneous nature of frontier society at the time, there was nothing unusual about the interracial marriage. But later as James Lougheed’s position grew, he had to face taunts of discrimination about his ‘Indian’ wife. If it ever bothered them they never let it show.”, p. 12

[4] “Canadian Women in the Public Eye”, SATURDAY NIGHT – “The Paper Worth While,”Sept 16, 1922