Securing Reserves and Other Land Quarrels

With larger trucks, hotter kilns and expanding markets for limestone products, the quarries in Beachville became eager to secure future supplies of the natural resource at the core of their work.

Land Purchases of the 1950s and 1960s

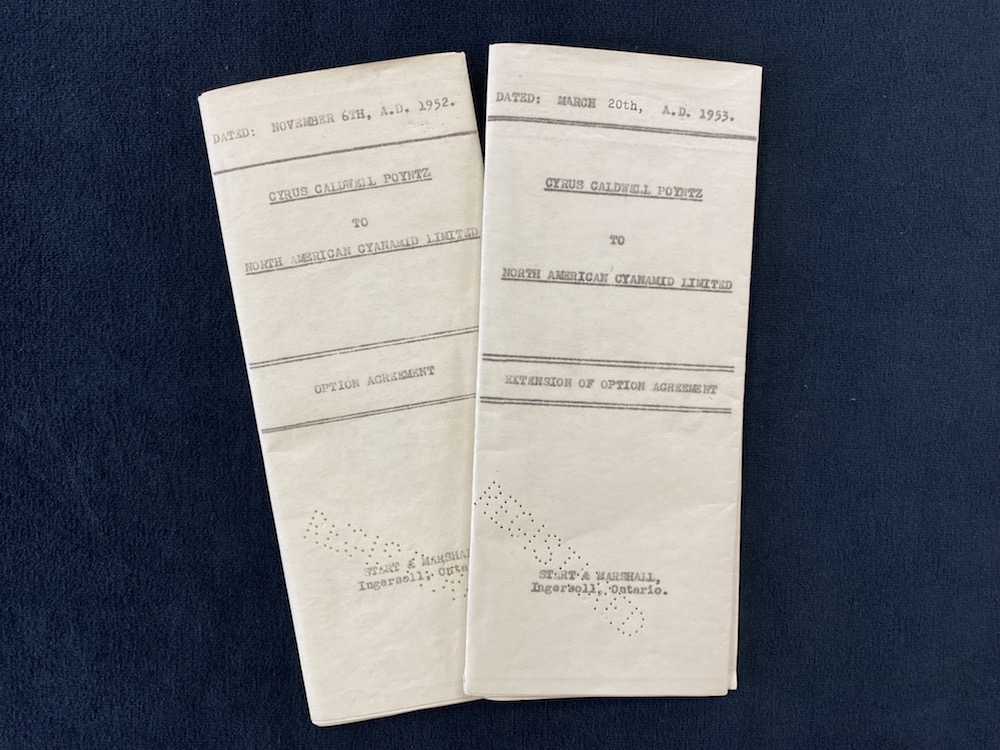

Option agreement and contract extension between Cyrus Caldwell Poyntz and North American Cyanamid, 1952/1953

Through the 1950s, North American Cyanamid purchased land tracts in the Beachville area from property owners. The agreements above were drafted between a farmer and Cyanamid in November of 1953. The contract and its extension allowed the quarry to buy a 50-acre property at the northwest quarter of Lot 16, Concession 2 in North Oxford, for $10,000. It also gave the quarry access to the lands for core drilling so that the company could assess the limestone deposit, rock quality, and depth.

Numerous agreements like this were drafted for the lime businesses in Beachville. By 1966, Cyanamid had claimed 504 acres in the area. Its competitors to the east and west, Stelco and Domtar, held 549 acres and 722 acres, respectively, and Canada Cement owned 604 acres. Cyanamid estimated that having purchased over 800 acres of property with stone reserves; it could steadily mine for about 100 years at a production rate of 1.5 million tons per year.

Quarry Quarrels

The areas around Beachville are home to many century farms. As land continued to be bought, many asked whether agricultural lands needed protection in the limestone valley corridor. Decades of quarrying also resulted in large, open pits; big businesses routinely eyed these pits as potential dumping grounds.

In the 1970s, the steel company that owned the former Cyanamid quarry proposed bringing 2 million tons of iron oxide waste from the Hamilton area to dump into the pits. Beachville area residents worried about the black dust blowing off trucks and polluting the local air. They raised concerns about increased traffic and the depreciation of their properties. Eventually, the steel company’s application to rezone the quarry to use as a dump was unsuccessful. The relationship between the residents of the limestone valley and their large industrial neighbours has been tested on many occasions.