Marconi in Newfoundland

Marconi arrived in St. John’s aboard the SS Sardinian in 1901. The first area of the city that he saw was Signal Hill: a great rock outcropping that towers 150 metres above the harbour. Immediately impressed by the site, he now had to find the best place to conduct his experiment.

The AATC Monopoly

This would be much easier said than done. As previously mentioned, the Anglo-American Telegraph Company (AATC) had a 50-year monopoly over telegraphy in Newfoundland. This meant that until 1904, only the AATC were allowed to use any form of telegraphy on the Island. Anyone who broke that rule could be sued or fined heavily.

When he landed in St. John’s, Marconi was well aware of this agreement. Instead of working with the AATC, he chose to lie about why he was in Newfoundland. To anyone who asked, he was there to conduct some experiments on ships in the area.

Finding a Location

Marconi met with Sir Cavendish Boyle and Sir Robert Bond (the governor and premier of Newfoundland, respectively), in hopes of gaining their support. The two agreed to help him, offering any space that Marconi wanted to work in. Marconi and his assistants went to Signal Hill in search of a spot. Cabot Tower was a prime candidate. It had only recently been built to commemorate the 400th anniversary of explorer John Cabot’s arrival in Newfoundland.

Many tourists visited Cabot Tower, however. This would make it difficult to hide the real reason Marconi was there, so he decided against it. Nearby on Signal Hill was an abandoned hospital building, which had been used for isolating contagious patients. It was quiet, it was solitary, it was empty. It was perfect.

Setting Up Shop

Because setting up 20 giant poles would draw attention to his work, Marconi had to come up with a new way to create an antenna. He had packed his radio equipment and antenna wire, but instead of mounting poles, he brought six 2.7-metre box kites, two 2-metre-wide balloons, and twenty-five tanks filled with hydrogen gas to lift the balloon. High winds might have ruined his original plans, but this time Marconi planned to use them to his advantage.

His team began testing the kites and balloons, to make sure they would be strong and reliable enough to do the job. This was no easy task. During one of his tests, wind broke the balloon free, sending it into the ocean, never to be seen again. The team eventually settled on using a kite—once they figured out how to raise one over 120 metres in the air. With their equipment set up and their antenna solution found, they were ready.

Success

On the morning of December 12, 1901, Marconi and his team prepared to launch their kite. They raised it to the desired height, but a strong gust of wind snapped its rope. The kite was lost to the Atlantic Ocean. Undeterred, they assembled a second kite and managed to get it all the way up and keep it there. Marconi powered up the receiving device and began listening.

Meanwhile in Poldhu, England, Marconi’s assistants were following their instructions. At specific times, they were to transmit the letter S in Morse code. Marconi thought this letter (three consecutive dots) would be the easiest to hear. The Poldhu station’s new antenna system was much simpler than the original. While not as powerful, they hoped it would be strong enough to get the signal to Newfoundland.

At the appointed time for their transmission, Marconi would be ready with his listening device in St. John’s. He had originally wanted to use a telegraph recorder, a device that would receive the signal and also print it onto strips of paper. However, telegraph recorders needed a fairly strong signal to receive a message. Marconi worried that the signal would be too weak by the time it crossed the Atlantic for the recorder to work, so he used a telephone receiver instead. With this, he would hear the message with his own ears—but there would be no printed evidence of it.

Marconi and George Kemp, his assistant, heard the first signal around 12:30 in the afternoon. Three dots crossed the Atlantic Ocean, a milestone accomplishment. To make sure it was not a fluke, they scheduled the Poldhu station to send the same message several more times that day and over the following two days. The St. John’s station successfully received the message multiple times from December 12 through 14.

The Secret Is Out

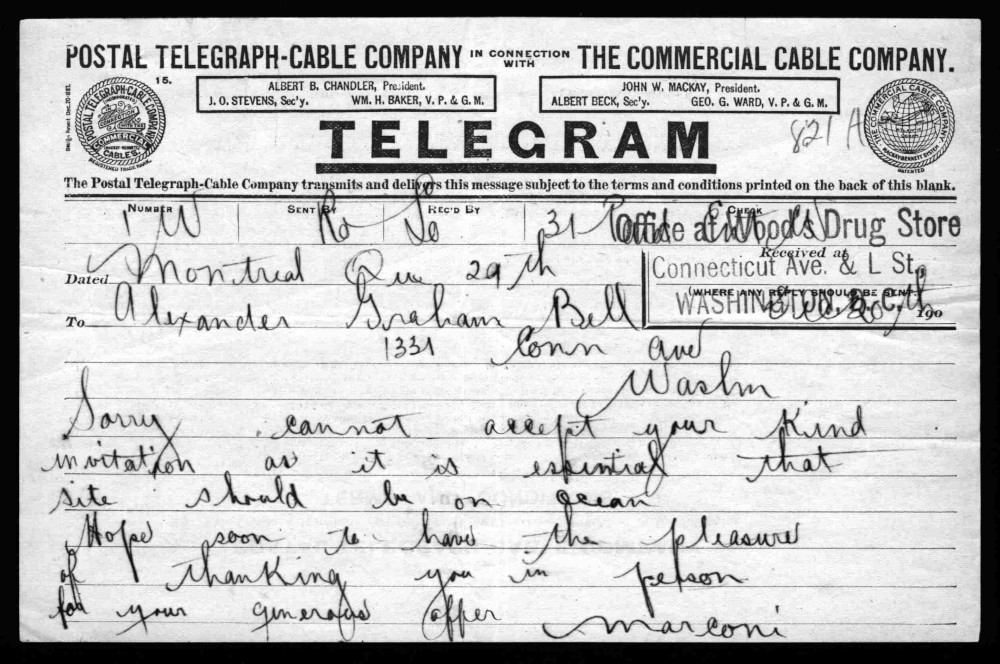

On December 15, Marconi shared the news of his achievement with reporters and by the next day he was making headlines all around the world. People were thrilled by the accomplishment. Alexander Graham Bell even offered Marconi the use of his personal estate in Cape Breton for further experiments.

Unfortunately, the AATC were not as happy about it. Marconi’s message made headlines on December 16. That evening, the AATC had their lawyer personally deliver a letter to him. It reminded Marconi of their contract with the government of Newfoundland. By performing wireless telegraphy, they said, he was in violation of said deal. Marconi knew that if he continued to work in Newfoundland, he would be taken to court.

And Marconi wanted to continue his work. The question became: where could he do it?

Marconi had wanted to build his first station at Cape Spear, Newfoundland. However, the AATC would not let him operate in Newfoundland while they held the monopoly on telegraphy. Preferring not to wait for three years, Marconi packed his bags and set his eyes on nearby Nova Scotia. He left St. John’s on December 24, 1901.