Placing the Blame

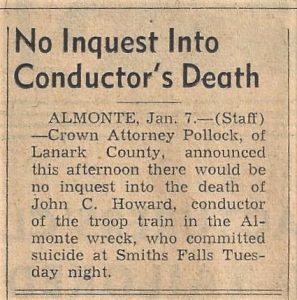

In the days following the train wreck, questions of how and why it happened hovered in the air. A coroner’s inquest was quickly opened in Almonte, the verdict spurred on by further tragedy: the conductor of the troop train, John Howard, was found in the Rideau River on January 6th. He had taken his own life, jumping into the frigid waters from Perrin Plow Bridge near his home in Smiths Falls. In a letter left to his son, he wrote. . .

I am sorry I have to do this, but I don’t want to go to jail. I was not responsible for that accident…God is my judge. I made no mistakes and I broke no rules. But I can’t stand it if they accuse me of causing 36 deaths.

Howard was 64 years old and nine months from retirement.

The results from the coroner’s inquest followed three days later in Almonte Town Hall. After a three-hour deliberation, the jury placed the blame firmly on the CPR, but not on the individual employees. The full text of the jury’s verdict was printed in the The Almonte Gazette on January 14th and included recommendations to protect the public. . .

The Results of the Coroner’s Inquest

It is our finding that the blame for this wreck must be placed entirely on the Canadian Pacific Railway Company for three reasons:

- First, they had no operator stationed at Pakenham when in our opinion the accident might have been avoided by the 20-minute block system.

- Second, there was no protective signal at a most dangerous curve, at the entrance to the town (Almonte).

- Third, the green light showing above the Almonte station gave the engineer of No. 2802 the impression that he might proceed. Had this signal been red, according to the testimony of the engineer and fireman, this train could have been stopped.

We recommend that in order to prevent the occurrence of a similar catastrophe and to safeguard the travelling public, especially under wartime conditions:

- That an operator be placed on steady duty at Pakenham.

- The immediate installation of an automatic station protective signal west of Almonte.

- That a standing order be issued for a speed limit not exceeding 25 miles an hour through Almonte and that this order be strictly enforced by the railroad officials.

- That the block-signal device at the station here be changed to give protection to the standing trains.

Despite the inquiry’s exoneration of the employees, a later investigation, conducted by the Board of Transport Commissioners for Canada, reached a different conclusion. Citing the troop train’s excessive speed and the passenger train’s failure to use a red or yellow flare, its findings stated. . .

There can be no other conclusion drawn from the facts but that had the rules been observed there would have been no accident.