A tribute to the Wolastoqiyik/Maliseet

Protectors of the nurturing Wolastokuk, from the past to the present

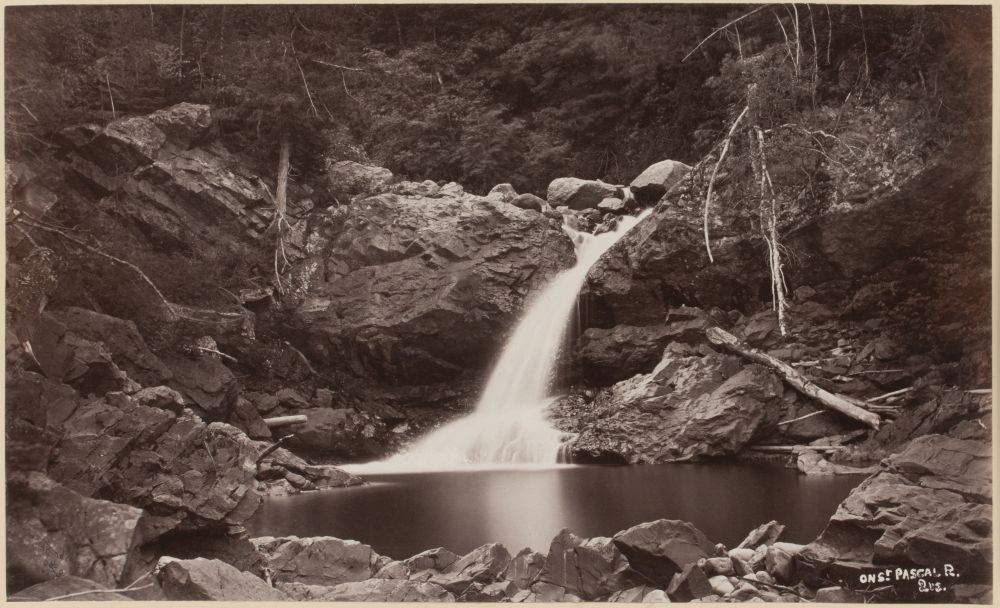

The Wolastoqiyik—more commonly known as the Maliseet by non-Indigenous people—are an Indigenous group whose history is deeply connected to the valley of the Saint-Jean River that flows through New Brunswick and Maine. Their name, Wolastoqiyik, means “people of the beautiful and bountiful river.” Prior to the arrival of Europeans, these Indigenous people occupied Wolastokuk, a territory stretching from the St. Lawrence Valley in Quebec to the White Mountains in what is now the state of Maine in the United States.

In the 17th century, when the first French settlers arrived in the Kamouraska region, the Wolastoqiyik people lived off the land. Over the centuries, they had developed a very close relationship with their environment, taking advantage of a wide variety of food resources depending on the season. The settlers were fortunate to be able to draw on the Wolastoqiyik’s thousands of years of experience. Eel fishing techniques, maple sap processing, and snowshoeing in winter are just a few examples.

Food resources in winter and fall

Meat was an important source of protein and fat that provided energy and comfort during the cold season, The Wolastoqiyik people hunted moose, white-tailed deer, beaver, hare, porcupine, waterfowl, and small game.

Food resources in spring and summer

Rivers and lakes were veritable pantries. Freshwater fishing provided a supply of salmon, trout, eel, sturgeon, and so forth. Marine mammals such as seals were hunted in salt water.

Forests and plains were an inexhaustible source of edible products. Gathering berries (blueberries, raspberries, strawberries), nuts, roots, pollen, flowers, and medicinal herbs was also part of the Wolastoqiyik’s everyday life, while farming in cultivated gardens produced corn, beans, and squash.

Influence of the environment on culture

Ancestral activities have shaped the lifestyle and culture of the Wolastoqiyik people, with their wealth of legends, traditional know-how, and artistic expression. They used basketry to make containers with traditional designs that served, among other things, for food storage.

Over the centuries, the Wolastoqiyik have developed a deep connection with their environment, taking advantage of a wide range of food resources depending on the season. Their diet, which was closely linked to their nomadic lifestyle, in turn shaped their culinary habits and cultural identity.