Broken Lives

Our Hearts Were Broken

In a move to assimilate and integrate First Nations people with settler society, the forcible removal of children from First Nation communities was sanctioned for almost a century by the Canadian government, separating them from family, society, culture, tradition and language.

From the 1890s up to the 1970s, children of the Stz’uminus First Nation, some as young as four years of age, were placed in several Residential Schools – the closest of which was located on nearby Kuper (now called Penelakut) Island.

Kuper Island Residential School

The Kuper Island Residential School opened in 1889. Run by the Catholic Church for much of its history, it operated until 1975. Both boys and girls attended. Its mission was “to provide manual and domestic training for Indigenous children of the Cowichan Indian Agency and adjacent Coast Salish groups”. The children were punished for speaking their native language and told that their traditional ways were ‘heathen’.

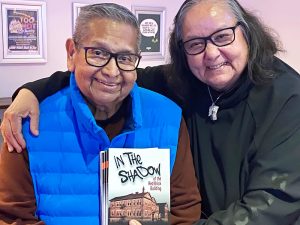

Author Tony Charlie and his wife Lorraine Charlie with a book he wrote chronicling his time at a residential school.

The history of the Kuper Island Residential School is tarnished by sad stories of abuse. It was not a nice place to be – an Alcatraz of the north, separated from Vancouver Island and the students’ families by several miles of sea. Home could be seen, but not reached. Desperately homesick and traumatized, several children drowned trying to escape by swimming or floating on logs across the water to Vancouver Island. One little boy made it across nine times, each time to be returned to the school by the local police.

The school building was demolished in the 1980s in an effort to expunge some of the painful memories. In 2021, the Penelakut First Nation reported the discovery of 160 unmarked graves around the former school site.

Cultural Revival

Former students and their families are to this day deeply affected by their Residential School experiences. However, the recent revival of First Nations culture and language is instilling pride in ‘who we are’. The process of Reconciliation is attempting to address past wrongs by returning traditional territory, listening, and stepping back to facilitate the self-healing of a community whose heart had been broken. No longer are indigenous ways viewed as ‘backward’ and ‘heathen’, but are seen to be respected and cherished within the cultural kaleidoscope of modern Canada.

Stz’uminus Elder George Harris composed the anthem ‘Stz’uminus Mustimuxw’, which is widely sung within the community, expressing great pride amongst members in the Stz’uminus First Nation and their Coast Salish culture.

Stz’uminus First Nation anthem (captions available in FR and EN). Enjoy this video with a transcript (EN).

Music Tradition

There was a musical tradition within the Kuper Island Residential School. In the early days (1890s – 1920s), the school’s brass band was renowned for its playing excellence. Brass instruments had been introduced initially by Catholic missionaries and were adapted by many First Nation communities for both recreational and ceremonial roles.

In Ladysmith, we are intent on Reconciliation and mending barriers within our community. It will take time and listening to what First Nation people have to say.