The great history of bilingualism in Canada

The history of bilingualism in Canada is long and complex. Prior to the arrival of the Europeans, First Nations people spoke several different languages and dialects. With the arrival of the French and the development of New France, French spread across North America, from Acadie to Louisiana. The conquest of 1760 changed the balance of power. North America became British. Even though the new leaders were English, the population of what was to become Canada remained largely francophone, despite the determination of the British authorities to assimilate the Canadians. Little known fact: the language of international communications being French in those days, the British elite in official positions in the Province of Quebec was largely bilingual.

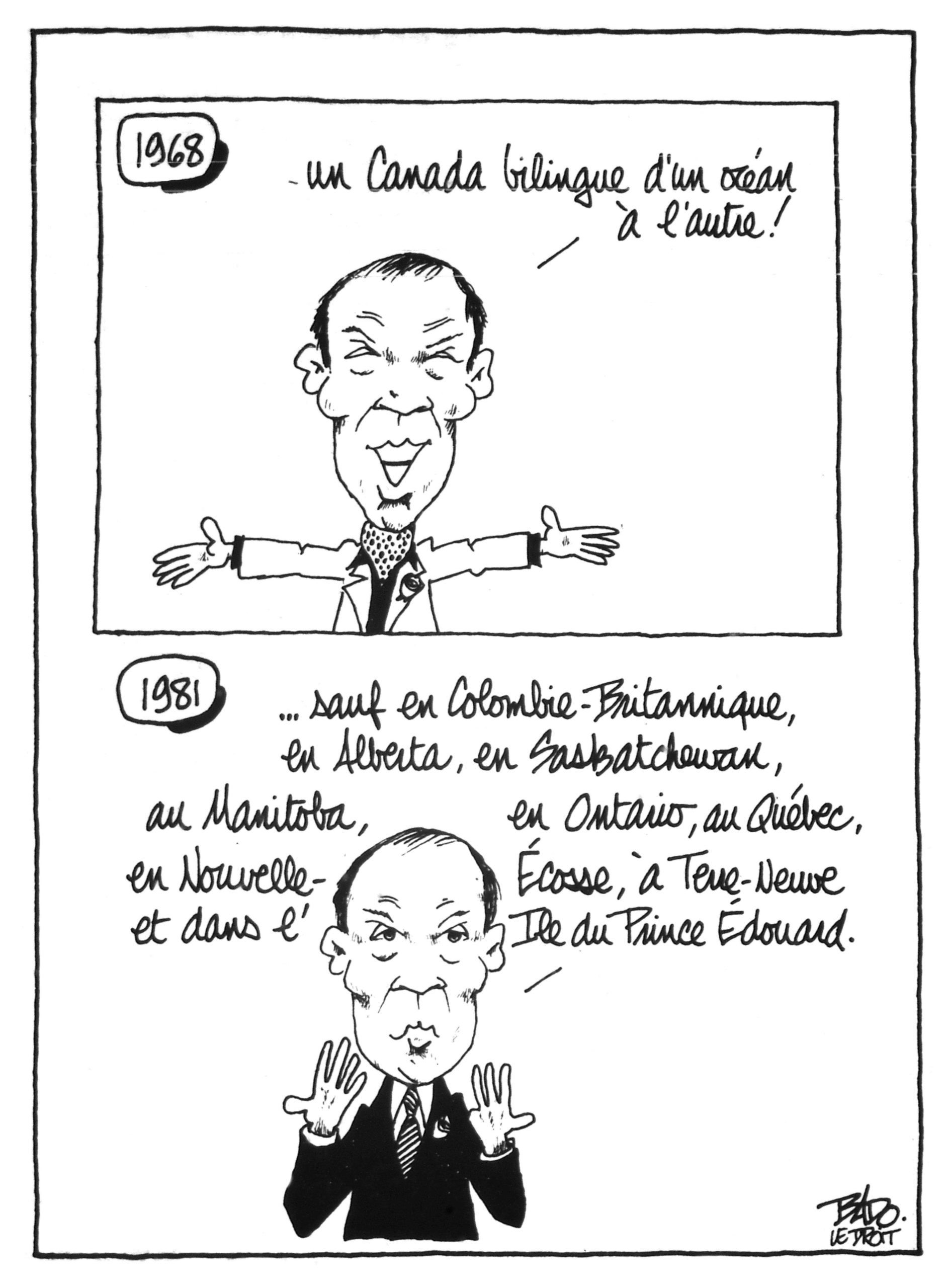

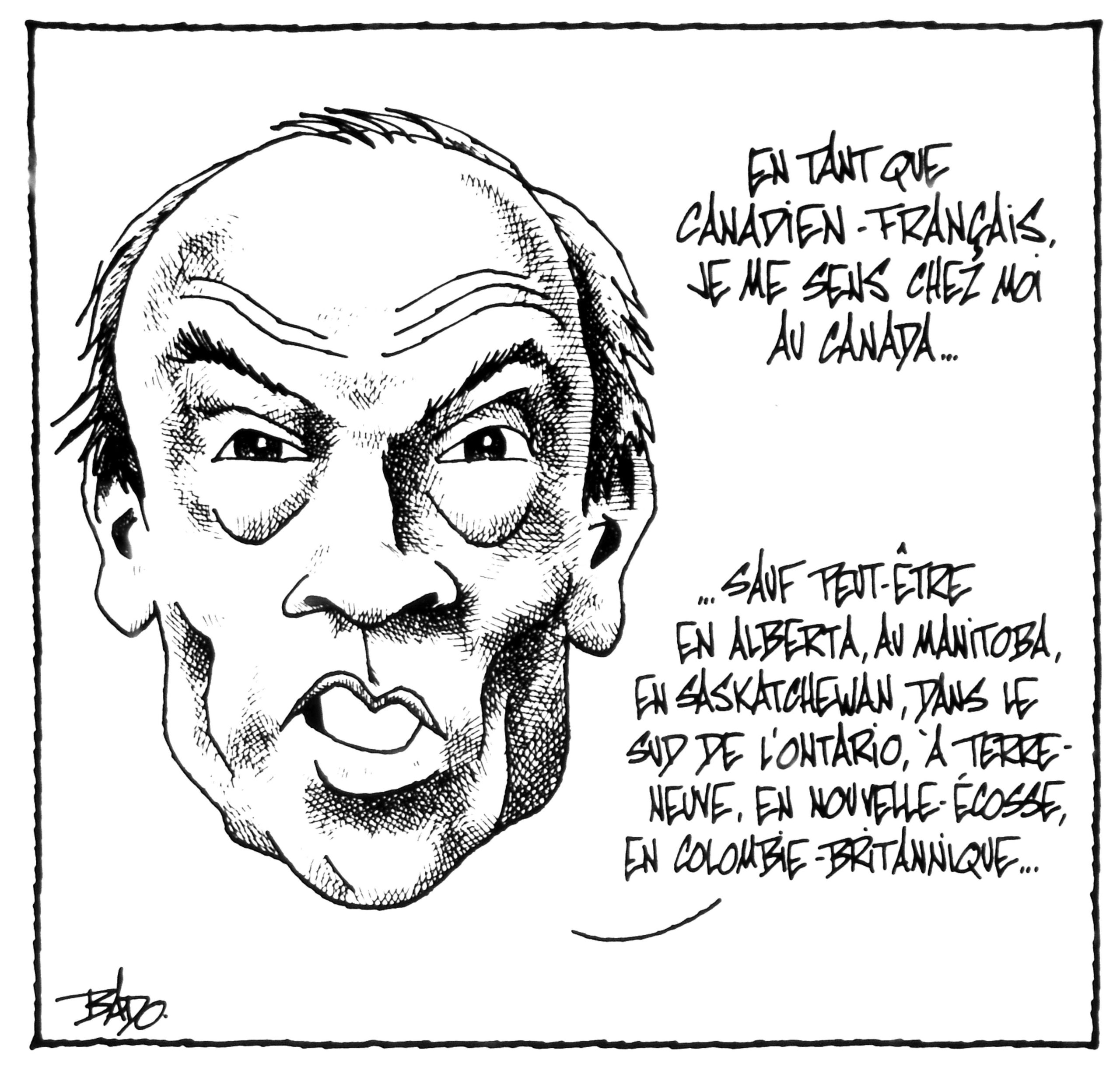

Heated debates marked the constitutional meetings that eventually led to the 1982 repatriation of the Constitution. Bado also took a stab at the bilingualism situation in Canada.

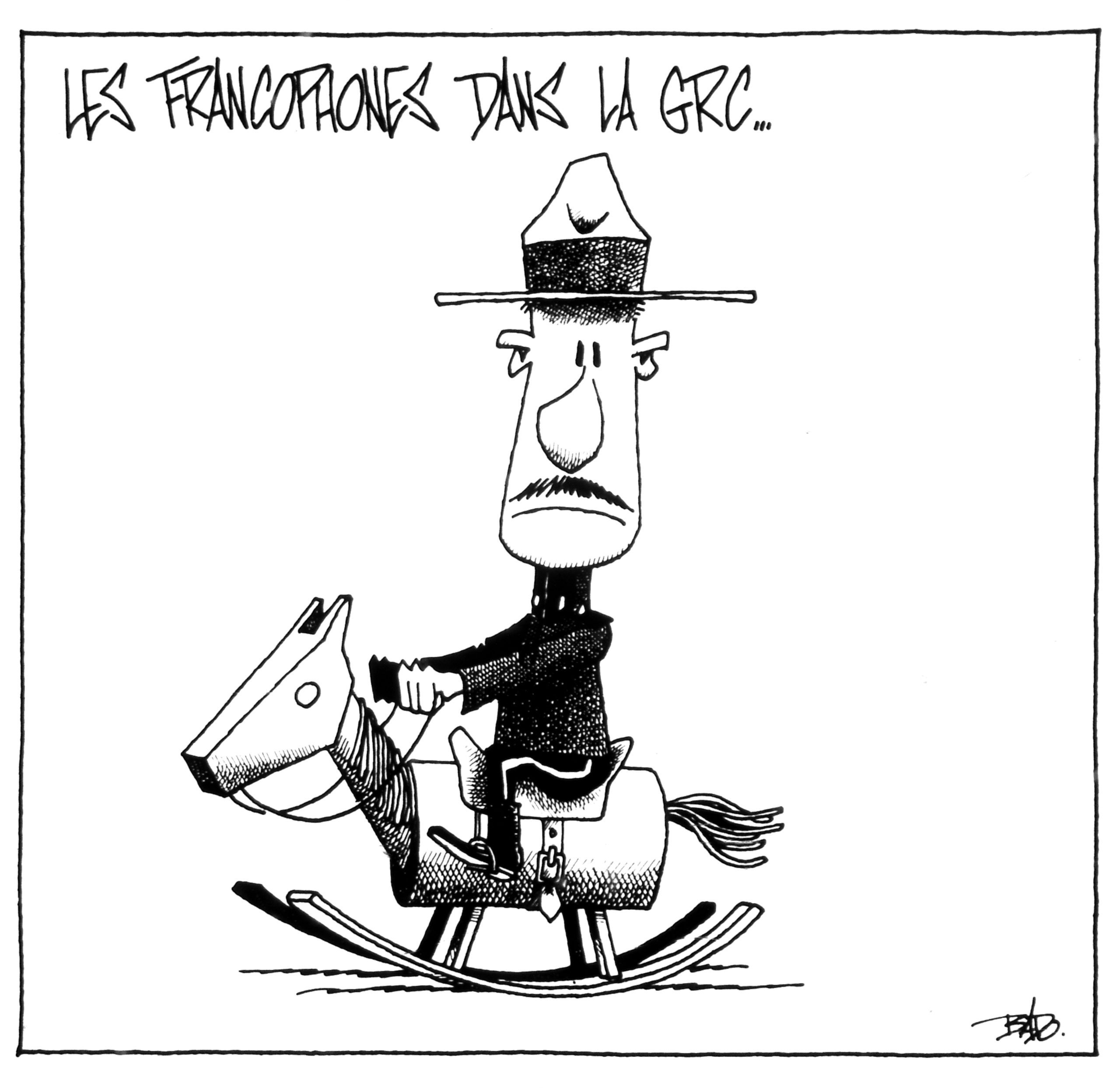

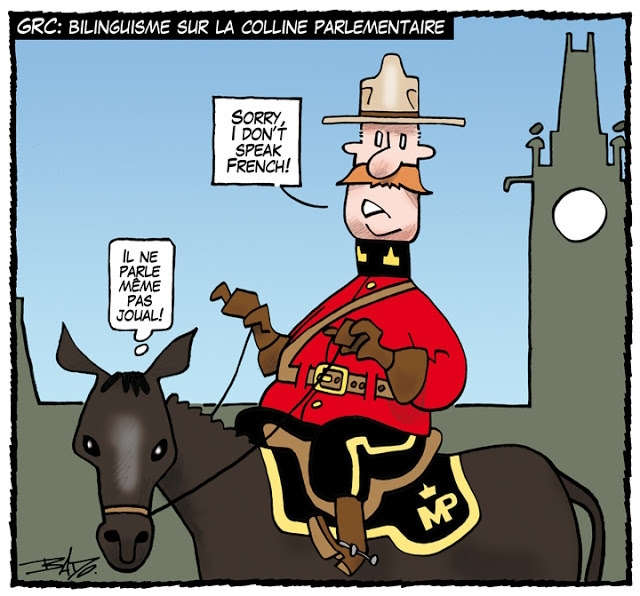

Awaiting an RCMP report to justify its intentions to reduce its targets for francophone recruitment from 20% to 14%.

It was not until the massive influx of loyalists leaving the United States after the War of Independence that the country’s population found itself in a situation of linguistic duality. Those British subjects settled in the various British colonies across North America (Quebec, which at the time included the territory now occupied by Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland), in the process significantly altering their demographic composition. Once the large majority, the proportion of francophones in those colonies fell to around 50%. For the only time in its history, Canada achieved true linguistic duality.

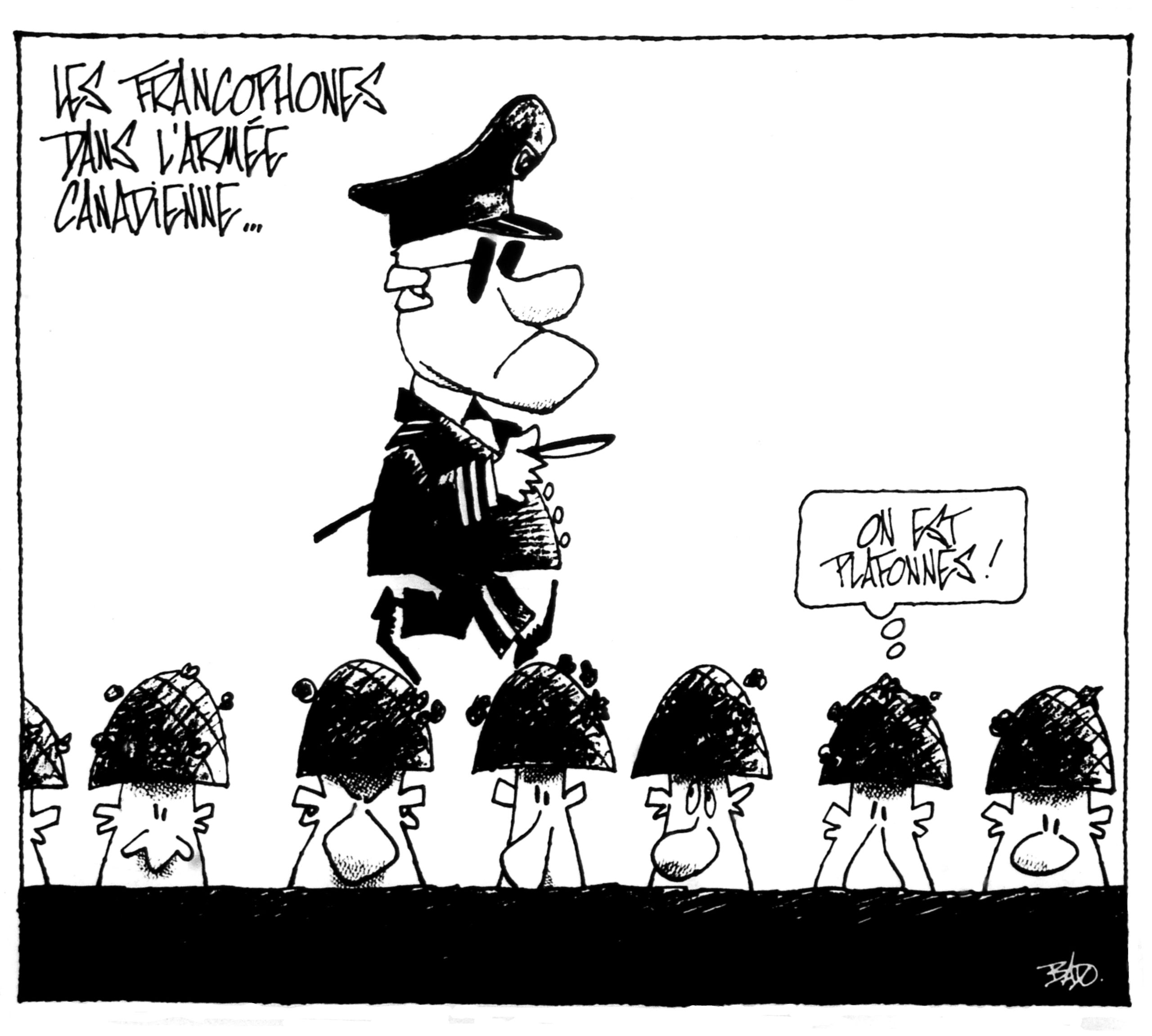

The Canadian armed forces management style discriminates against francophones, who are forced to set aside their cultural identity if they want to be promoted or simply keep their position. An investigation was ordered by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

Right in the midst of negotiations on the Meech Lake Accord, former Prime Minister Pierre Eliott Trudeau releases a book on his years in power, in which he openly criticizes the constitutional negotiations.

In the early 19th century, the colonies’ political structure was defined. The Constitution of 1791 introduced parliamentarianism, and gave the francophones of Lower Canada a certain autonomy, even though the last word fell to the Governor General and the Lieutenant Governor of each colony. However, that did not prevent the appearance of the first actual linguistic conflicts in Lower Canada. While the parliament of Lower Canada practiced a degree of bilingualism, in Upper Canada, anything having to do with the French language and civil law was systematically blocked. The Loyalists considered that the province of Upper Canada was created expressly for them, and issues related to French were simply dismissed. The colonies’ legislation also ensured that English was the only official language.

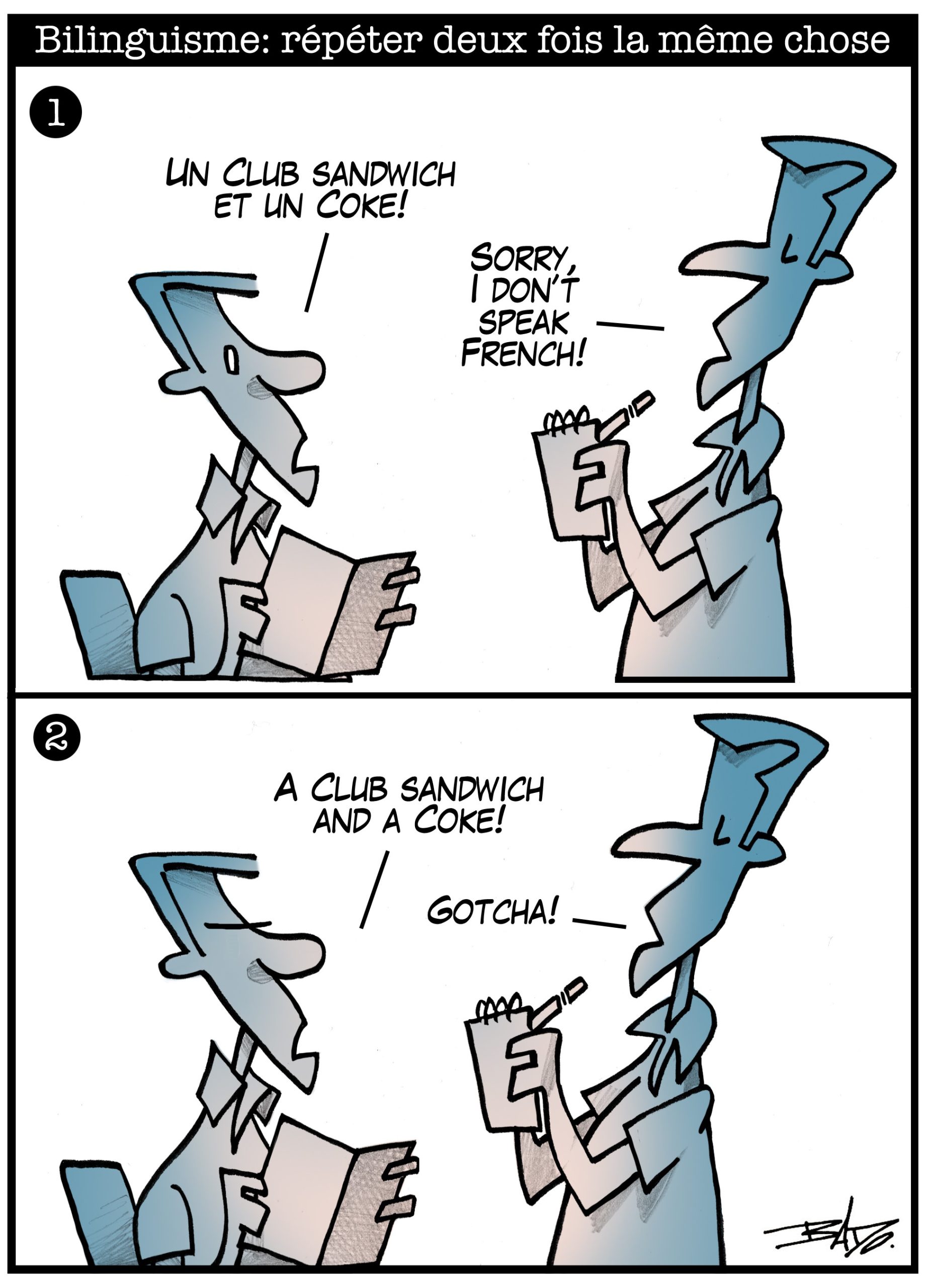

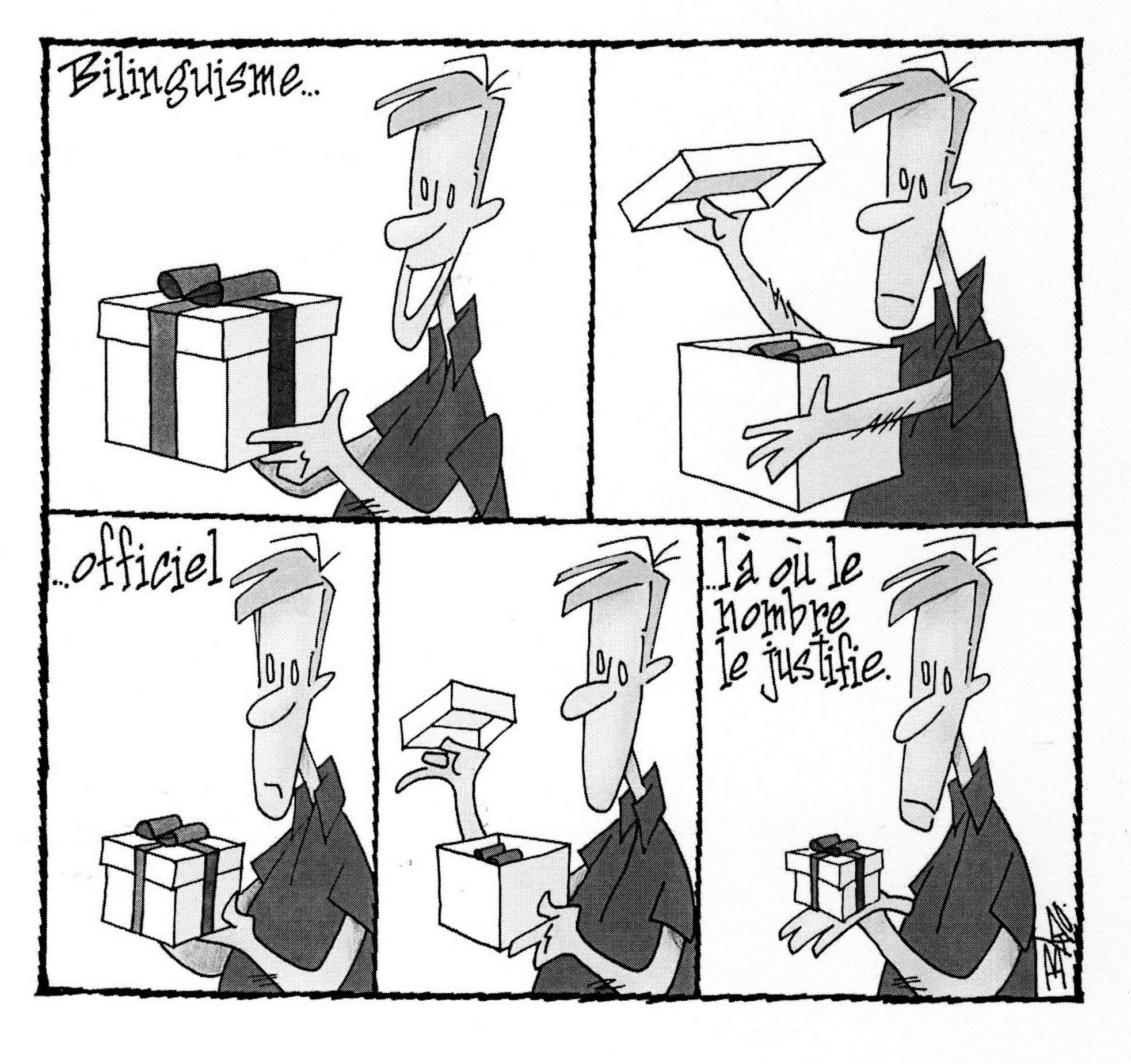

Reflecting on the state of bilingualism in Canada. Bilingualism rules only apply where justified by the numbers.

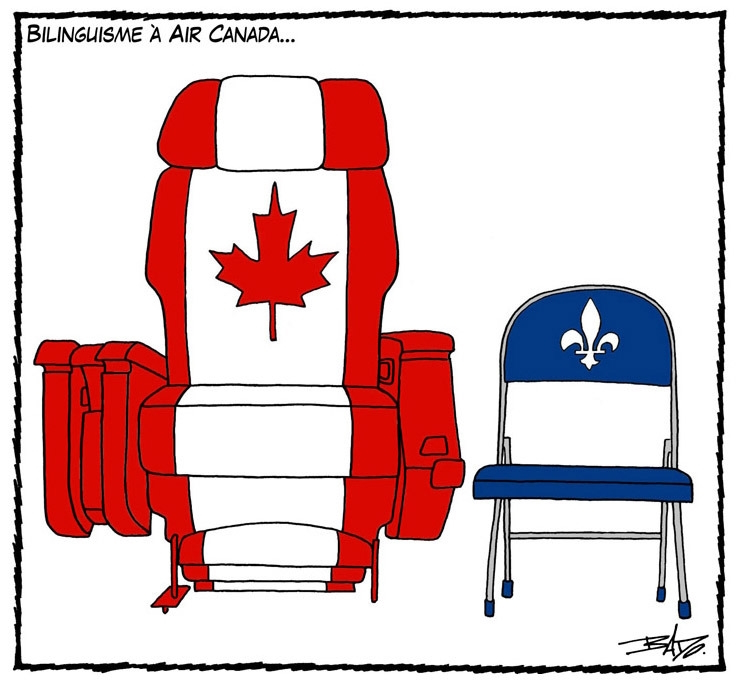

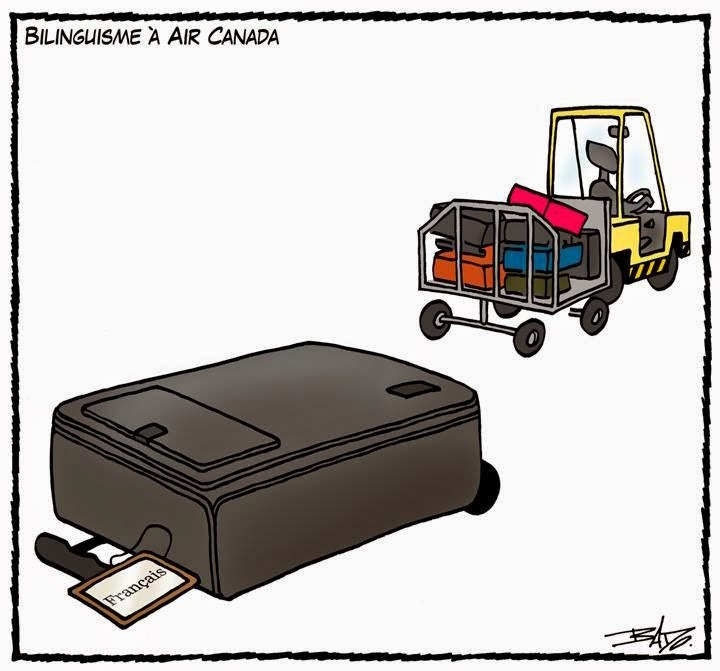

A report by the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages accusing Air Canada of not trying to recruit francophone pilots and continuously complicating the work of the Office’s inspectors.

The first half of the 19th century saw the rise of francophone nationalist feelings in Lower Canada. The movement culminated with the Patriot Rebellions of 1837-1838. Governor General Durham was asked to review the situation and resolve it. In Lower Canada, he noticed that two nations were at war in a single state. Thus, he submitted a report suggesting that Upper and Lower Canada be united in order to assimilate the French Canadians. That report led to the Act of Union of 1841. It is hardly surprising that English was designated as the official language of that new political entity, even though half the population was francophone.

Pierre Lemieux, Conservative MP for Glengarry-Prescott-Russell, in Eastern Ontario, opposing draft legislation that would require the appointment of bilingual justices to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The Supreme Court sides with Franco-Ontarian Michel Thibodeau against Air Canada, finding it guilty of failing to comply with language rights. However, the airline did not have to pay any compensation because the Official Languages Act violations occurred outside Canada.

A major political shift occurred in 1867. The adoption of the Constitution Act, 1867 laid the foundations of what would become modern Canada. The new Constitution highlighted bilingualism, officially making English and French the two legislative and legal languages of Canada. In terms of the provinces, that principle applied to Quebec and Manitoba, which joined the confederation a few years later, and a significant part of whose population consisted to francophone Métis people. However, that principle was completely ignored in the other provinces. Even the signatories to the Constitution Act diverged greatly in their interpretation. For Georges‑Étienne Cartier, the Constitution Act gave Quebec the right to protect its language, its religion and its civil law. For others, it was the chance to finally celebrate the demise of a certain French Canada and the birth of an English and Protestant Canada. In the first century of Canada’s Constitution, the federal government adopted a language policy of non-intervention, leaving the provinces to legislate as they wished on the language issue. It should be noted that French remained largely figurative in the federal apparatus. Although laws and regulations were in both languages, most of the federal public service operated exclusively in English.

The RCMP, posted on Parliament Hill, breached the Official Languages Act with officers who were unable to offer services in French to the public.

The Government appoints bilingual justices to the Supreme Court, but does not plan to table draft legislation to formalize that practice.

At the turn of the 20th century, several provinces enacted a series of laws and regulations that largely restricted French-language education. One of the saddest examples remains the famous Regulation 17. Passed by the Government of Ontario in 1912, that regulation prohibited French-language education in the province’s schools. Among the military, as well, the situation was hardly better. A few years after the start of the First World War, many English Canadians accused francophones of failing to step up to serve in an army where everything happened only in English. The creation of a unit that would become the legendary Royal 22nd Regiment improved things somewhat for French Canadians, but for a long time English would remain the language of officers. Nothing changed in the Second World War. The few francophone units were restricted to the land forces. The air and navy forces remained exclusively anglophone. In addition, the conscription crisis of 1942 would greatly exacerbate the tension between the country’s anglophones and francophones.

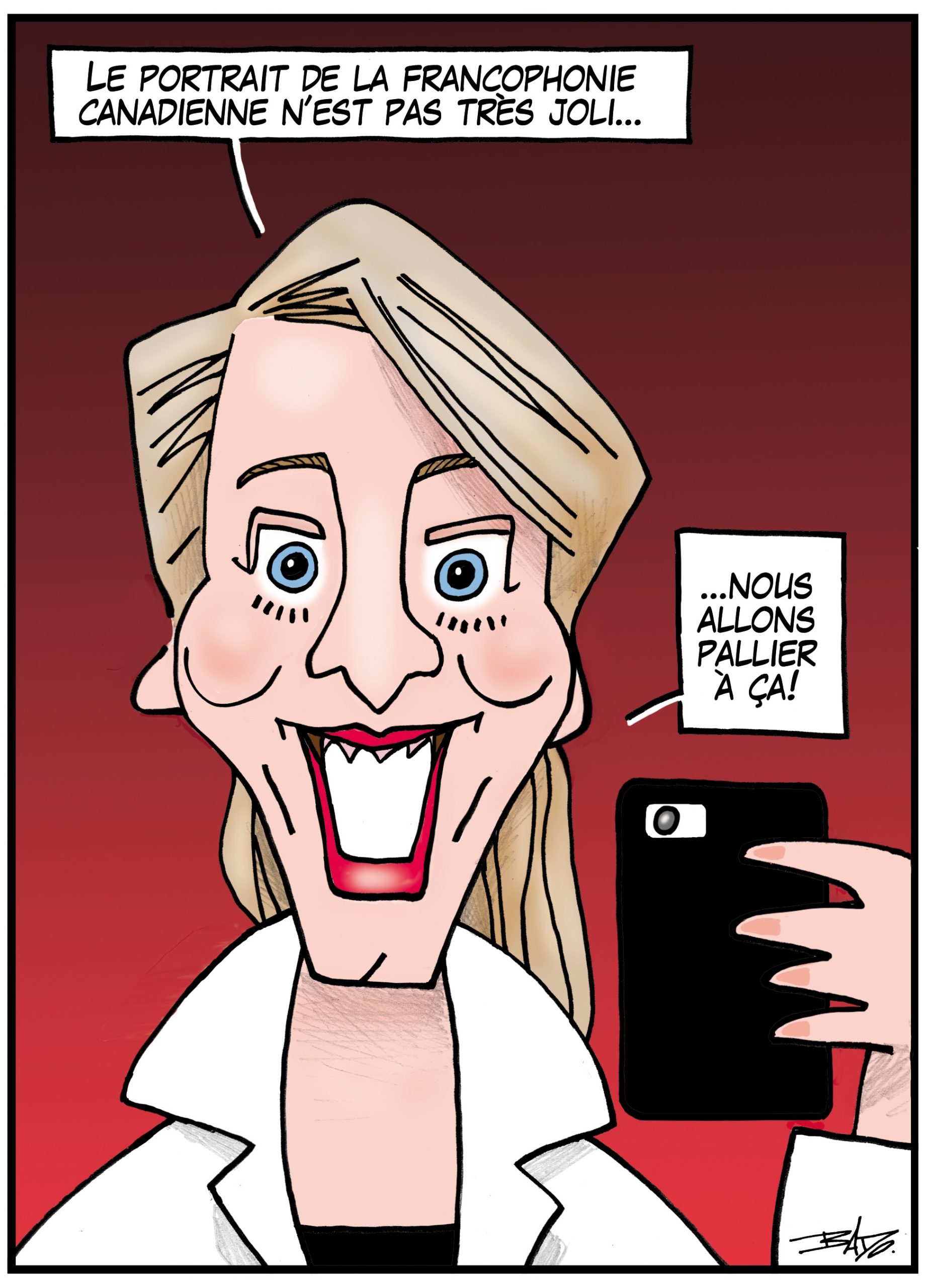

Mélanie Joly, Minister of Canadian Heritage and Official Languages, unveiling unimpressive statistics on Canada’s francophonie.

Nonetheless, the first half of the 20th century would be marked by a few wins for bilingualism. The bilingualization of stamps, bank note and pension cheques, the creation of the Société Radio-Canada, and the francophone presence in the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), represented progress for French Canadians. Those advances were in part due to the actions and pressure exerted by the Ordre de Jacques‑Cartier, a secret society dedicated to defending the interests of French Canadians and advancing them within the federal public service.

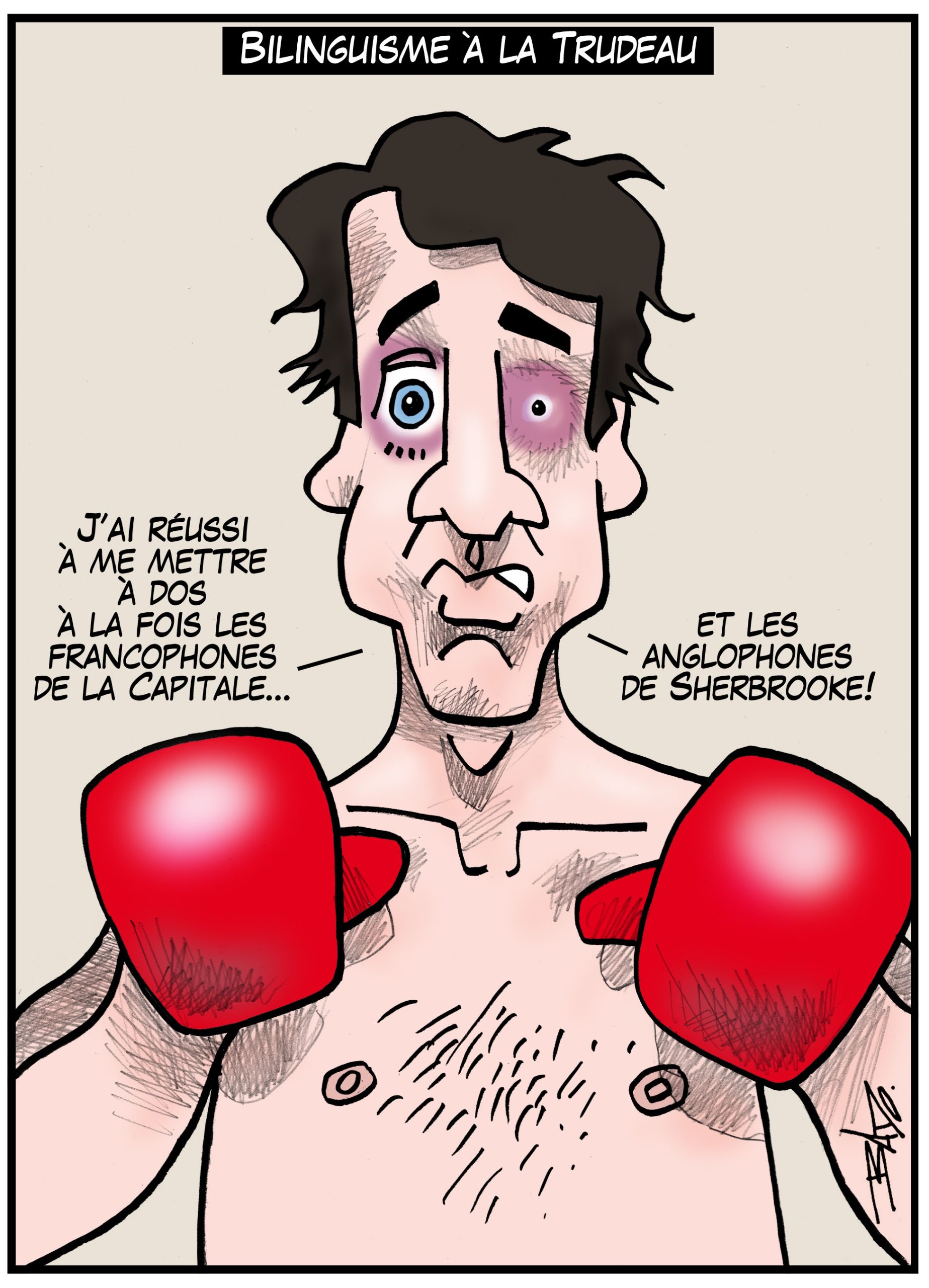

Justin Trudeau incurring the wrath of several citizens by answering in English questions asked in French in Ontario, and questions asked in English in Sherbrooke, in French.

A paradigm shift occurred in the 1960s. A change that would also be observed internationally, as several countries adopted language laws. The election of Lester B. Pearson as Prime Minister in 1963, marked the beginning of that new linguistic vision with the establishment of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (the Laurendeau-Dunton Commission). This new momentum was accentuated by the election of Pierre Eliott Trudeau, who would bring in the Official Languages Act.