Commercial Broadcasting and Radio Receiving Sets

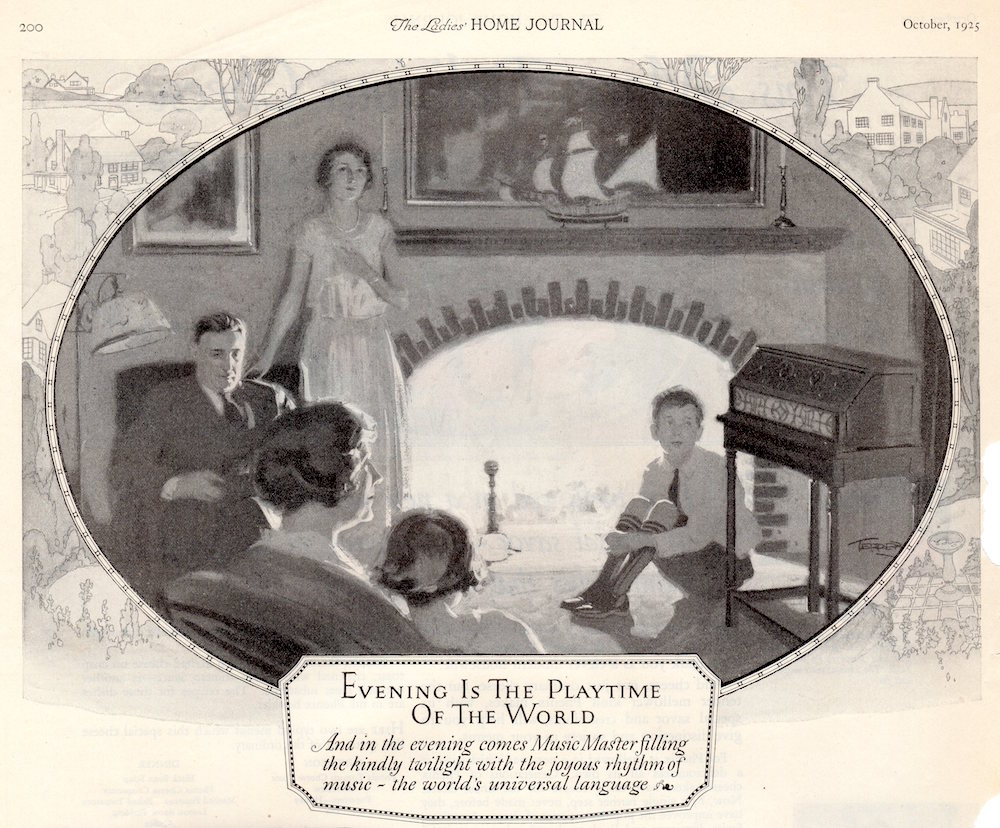

“Evening is the Playtime of the World,” Ladies Home Journal (October 1925): pp 200 (cropped). Musée des ondes Emile Berliner.

Broadcasting in Canada started before the First World War. During the war, radio broadcasting was restricted to military operations. Not long afterward, experimental broadcasting resumed. On December 1, 1919, experimental wireless apparatus (XWA) owned by Marconi Wireless Telegrpha Company of Canadabegan broadcasting in Montreal. The station changed its call letters to CFCF in 1922 when Canada first issued commercial broadcasting licenses. As commercial stations started to extend their coverage across the country, Canadian radio ownership rose at a rapid rate.

On left: Radiola Loudspeaker Model 104 (1925), New York, United States, 103 x 54 x 34cm; on right: RCA Radiola 28: Model AR-920 with Antenna (1925), New York, United States, 26 x 69 x 42.5cm. Musée des ondes Emile Berliner.

With the rise of commercial broadcasting, self-contained radio receiving sets became more popular. Floor models, like this 1925 RCA Model AR-920 with antenna and radio loudspeaker, were common sights in the homes of the affluent. Models with knobs for fine tuning sold well in urban centres. The listeners had a variety of stations on the dial to choose from.

Once radios entered the home, they needed a place to stay. The floor model was expensive, but it was a piece that could stand on its own in a parlour or a living room. Companies designed radio receiving sets made of wood to be attractive. The design reflected its value and made it suitable for those family gathering rooms.

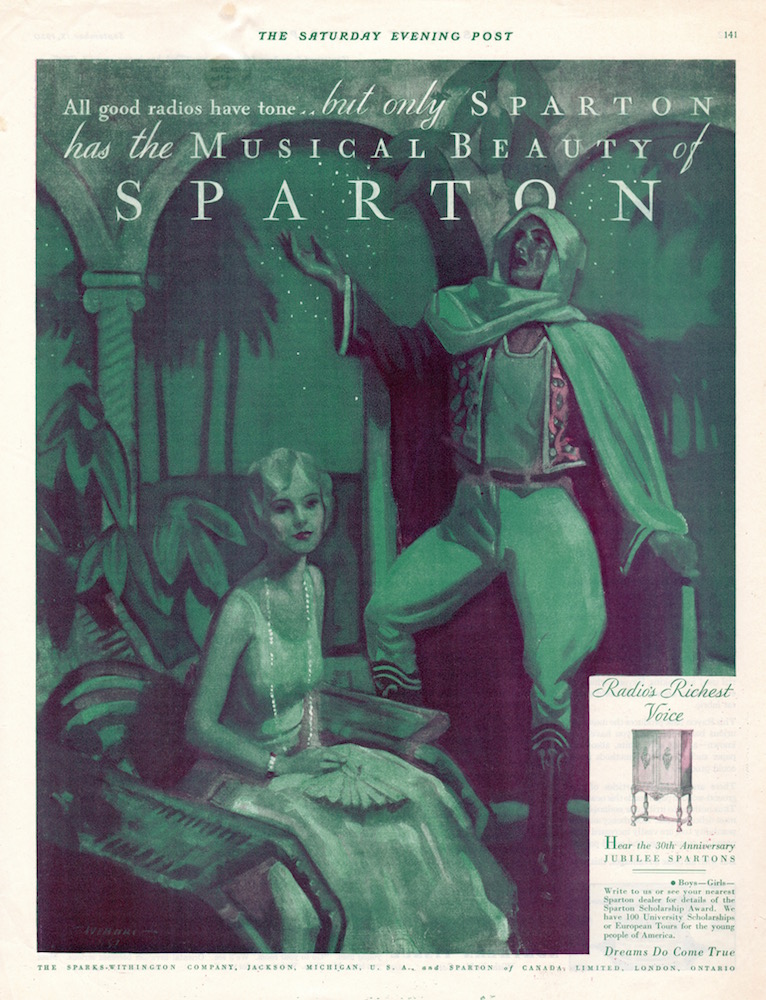

Radio advertising not only extolled the technical attributes of each radio but also its beauty as a wonderful addition to the furniture of any home. The expensive floor models purchased in the 1920s and 1930s could cost as much as one week’s wages. They were still too expensive for many Canadians who continued to use their crystal sets. Shopping for a sophisticated radio was not based on comparison of sound. Usually, customers considered technical specifications and beauty.

Sparton Advertisement, Saturday Evening Post (September 1930): pp 141. Musée des ondes Emile Berliner.

Radio provided imaginary worlds for its listeners that allowed everyone to dream about the lives of the wealthy. Even if you couldn’t afford the Eisenmann radio in the ad above, you could almost feel like you were sneaking into the ball from your own home.