A Bitter Strike

In the early 1900s, accidents and fatalities in the coal mines were all too common. The miners wanted safer working conditions, better pay, and the right to join a union. The coal companies opposed this as it increased their costs. Tensions rose.

In June 1912, a union member who had reported gas in one of the Extension mine shafts was fired; the company considered him a troublemaker. He was blacklisted and dismissed from his next job.

This sparked off a strike which quickly spread to the other mines on Vancouver Island. Supported by the United Mine Workers of America union, it was time for the miners to take a stand!

However, union strike pay was not enough to live off: the miners and their families suffered greatly. To keep spirits up, the union rented a large hall in Ladysmith with games rooms, a library and a piano for concerts. Christmas 1912 was celebrated with music and dancing.

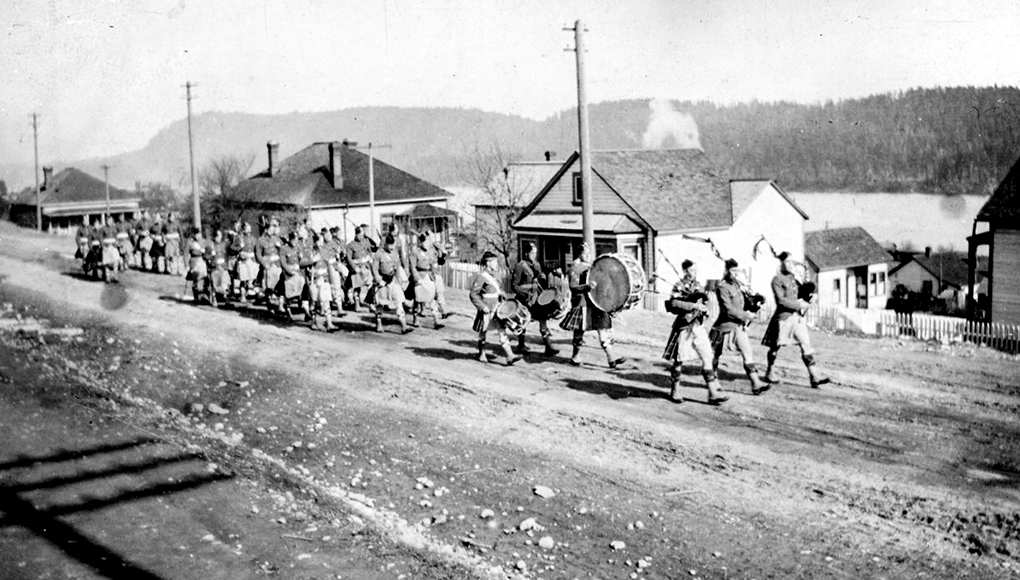

72nd Regiment Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, led by pipers, march north along First Avenue, Ladysmith in 1914.

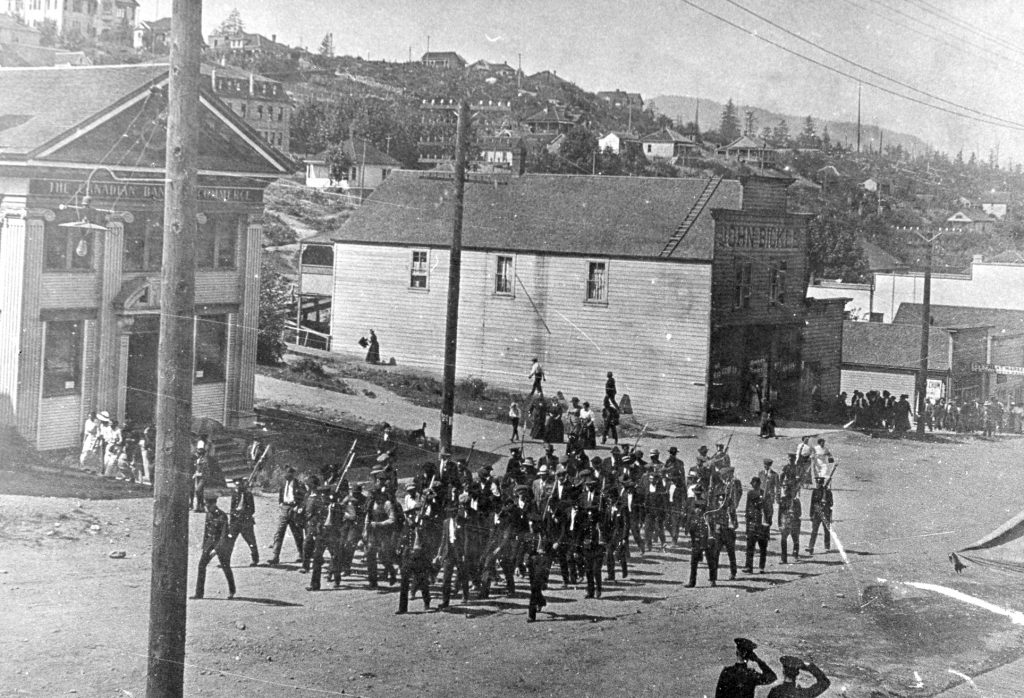

On May Day 1913, thousands of miners, their families and union supporters paraded in Ladysmith in a show of solidarity. A brass band led the way.

Words of the song ”Bowser’s Seventy Twa”, in the British Columbia Federationist Newspaper. April 24, 1914. (Click on image to see transcript).

However, the coal companies refused to concede: instead, they reopened the mines using strikebreakers.

Very hard feelings between strikers and strikebreakers culminated in riots in Ladysmith and Extension in August 1913. Property was destroyed; two bombs were thrown, one blowing the hand off a strike-breaker.

The militia was sent in by the Attorney General, William Bowser, to impose order. This was NOT popular with the miners who composed and sang an uncomplimentary song about the 72nd Regiment, Canadian Seaforth Highlanders: “Bowser’s Seventy Twa”.

Bitter Strike (captions available in FR and EN). Enjoy this video with a transcript (EN).

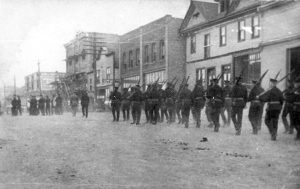

Members of the 5th (BC) Field Artillery Regiment Militia march along 1st Avenue in Ladysmith during The Great Strike.

Fifty miners were sentenced to prison. When dozens returned to Ladysmith in the Spring of 1914, they were paraded through the streets to a loud rendition of “La Marseillaise.”

Still, the coal companies did not bend. In July 1914, the union ran out of money and cut off strike pay. In August, two weeks after the outbreak of World War I, the miners reluctantly returned to work, ending one of the most bitter strikes ever in British Columbia.

Bad feelings would divide the community for generations.