Putting it on Paper

When words are printed or recorded, they can make a more lasting impact. Printed materials can be passed around and shared, greatly increasing the numbers of people who can be reached.

From the time that printing presses utilizing mechanical moveable type appeared in Europe in the 1400s, printing has played a key role communicating ideas, sometimes in support of the existing social order, often in advocating change.

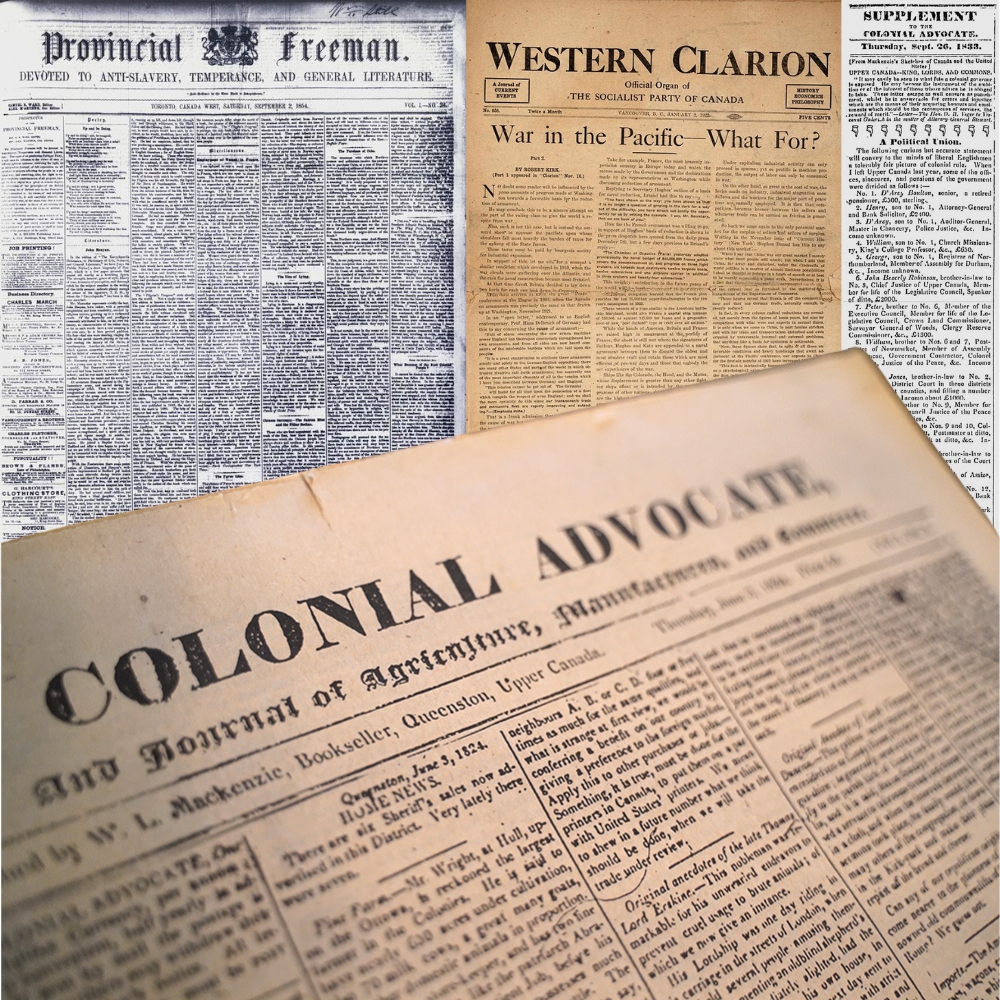

The first printing press was brought to Canada in 1751 and used to launch Canada’s first newspaper, the Halifax Gazette. Early newspapers were commonly founded to advance the publisher’s opinions as much as they existed to report ‘news,’ and at times they played a crucial role in shaping political attitudes. Prominent examples from the 19th century include Le Canadien, which first appeared in Quebec City in 1806, William Lyon Mackenzie’s Colonial Advocate, published in Upper Canada in the 1820s and 1830s, and Mary Ann Shadd’s Provincial Freeman, published in the 1850s.

Early newspapers consisted of dense columns of type. Printing was expensive, so it made sense to pack as many words onto each page as possible. However, by the second half of the nineteenth century, improvements in printing technology, the graphic arts, and photography made it possible to produce illustrated magazines. Publishers of magazines and newspapers soon found that readers were more likely to buy their publications if they were illustrated.

In addition to art and photographs, newspapers and popular magazines frequently published cartoons, which conveyed comments on politics in a simple and interesting way. Radical newspapers featured their own cartoonists, who expressed a critical point of view often quite different from that found in mainstream publications. Cartoons can be considered a form of media in their own right.

Once a publication was produced, it had to be distributed to its readers. For many decades, and still continuing into the present, the Post Office was the main way that periodicals of all kinds, including left and alternative publications, were distributed. Activists did use other methods for distributing their newspapers, for example by selling them or handing them out at factory gates, on picket lines, or on street corners, but the hope was that at least some of those who received a copy would then sign up to have a subscription mailed to them.

Beyond the main methods of ‘getting the word out,’ activists have employed an almost limitless variety of means of communicating their messages, from picket lines to theatre performances, puppet shows, public singing, flags, homemade signs, games, murals, and graffiti.