Indigenous Vernacular Art

Indigenous vernacular art offers a unique view of the Prairies, focusing on spiritual connection with the land. The buffalo is a key symbol of this connection. It appears in early work by Kainai artist Percy Plain Woman and in more recent works by Siksika artist Adrian Stimson. It represents individual and collective narratives of relationships with the land. These artworks are like visual stories, much like the oral traditions of Indigenous peoples. They reflect almost eighty years of cultural history.

The earliest generation of Indigenous artists in this exhibition often faced challenges. They dealt with unfair judgments from the art world, and faced limited appreciation of their contemporary paintings.

Terms like “calendar art” were used to belittle the work of Indigenous artists like Allen Sapp, Henry Beaudry, and Bette Spence. It limited their works’ exhibition and collection potential. Bob Boyer, a Métis artist and curator, challenged this label. He curated Sapp’s retrospective exhibition, Kiskayetum, in 1994 at the MacKenzie Art Gallery. Boyer argued that calling Sapp’s work “calendar art” unfairly limited its potential and misunderstood its importance. He saw Sapp’s art as visual storytelling. A way of sharing moments of early reserve life, contributing to an Indigenous art history influenced by knowledge shared across generations of lived experience.

Sapp, Plain Woman, and Beaudry capture moments from reserve life. They tell stories through visual art, much like traditional Indigenous paintings on hide depicting battles or heroic acts. Sapp’s paintings of powwows and everyday activities, Beaudry’s depiction of the signing of Treaty No. 6, and Plain Woman’s Last Buffalo Hunt show changing ways of life for Indigenous people. In 1987, curator Carol Podedworny called these artists “narrative realists”. She felt their work reflected the unique philosophical view of Indigenous nationhood.

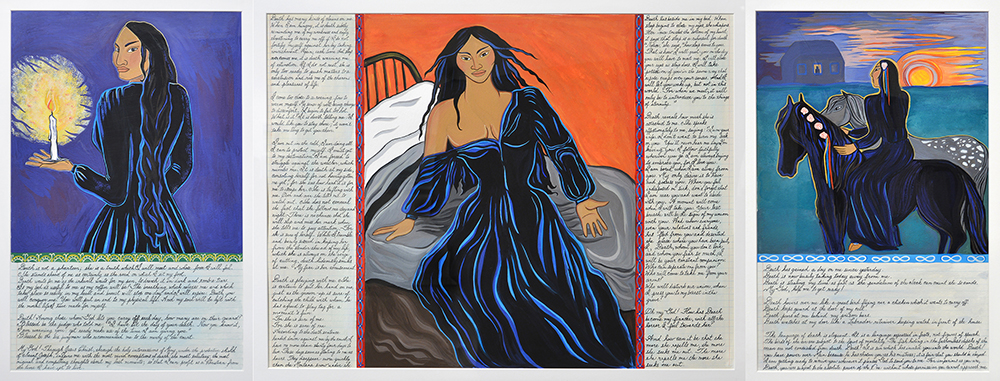

Bette Spence’s work also depicts memory scenes of prairie life, though as a female artist, her artistic expression was influenced by different cultural traditions. Even so, her art, like that of her male counterparts, reflects the power of the land and plays with themes of time and space.

In the 1990s, Indigenous art became more political, addressing colonial trauma directly. Artists like Sherry Farrell Racette, Allen Benjiman Clarke, Adrian Stimson, and Ruth Cuthand used their work to confront cultural loss and erasure. Cuthand’s drawings highlight the racism she experienced as a teacher. Racette’s haunting Riel’s Vision of Death; 1885 comments on colonial impacts on Métis history. Clarke’s powerful works express personal and collective trauma from the residential school experience.

See Bibliography for sources.