The official languages

The notion of official languages in Canada emerges in the late 1960s. The Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1963-1969), aka Laurendeau-Dunton Commission, named after its two commissioners, tackles the country’s language and cultural issues faced by the francophone and anglophone “founding people”.

In her annual report, Commissioner of Official Languages Dyane Adam deplores the federal government’s lack of determination to entrench its political promises.

It should be noted that issues related to the place of First Nations are not on the table at the time. It should also be remembered that Canada’s language situation is in upheaval as it faces the rising tide of Quebec nationalism. The Commission’s report is heavily based on the concept of biculturalism and the recognition of two official languages. In fact, one volume of the final report is exclusively dedicated to that issue.

The Trudeau Government passes the Action Plan for Official Languages. The plan provides for the addition of $500 million over five years to allocations for minority language communities.

The Federal Court declares that the obligations of federal institutions under the Official Languages Act are not well defined. This situation disadvantages Canada’s language minorities.

After the report is tabled, the Pierre-Elliott Trudeau Government pushes through the Official Languages Act, which forces the federal government to serve citizens in both languages. However, it does not address the whole aspect of biculturalism, which was so important to André Laurendeau, instead opting for a multicultural approach that often puts English in a dominant position.

The federal government sets about modernizing the Official Languages Act with upcoming consultations.

The Official Languages Act’s modernization provides for discussions of the development and growth of minority official language communities, mainly anglophones in Quebec and francophones outside Quebec. Communities with vastly different realities.

Language rights in Canada are strengthened with the adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982. In 1988, a second Official Languages Act is passed by the Conservative Government of Brian Mulroney. This revamping of the Act establishes the equality of the two languages in federal courts. It also bolsters minority language communities and creates the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, which is tasked with ensuring that the main purposes of the Official Languages Act are achieved.

The federal government is in the process of updating the Official Languages Act. The Standing Committee on Official Languages tables its report on modernizing the Act in mid-June.

The new modernized version of the Official Languages Act would, in some cases, help strengthen French in Quebec.

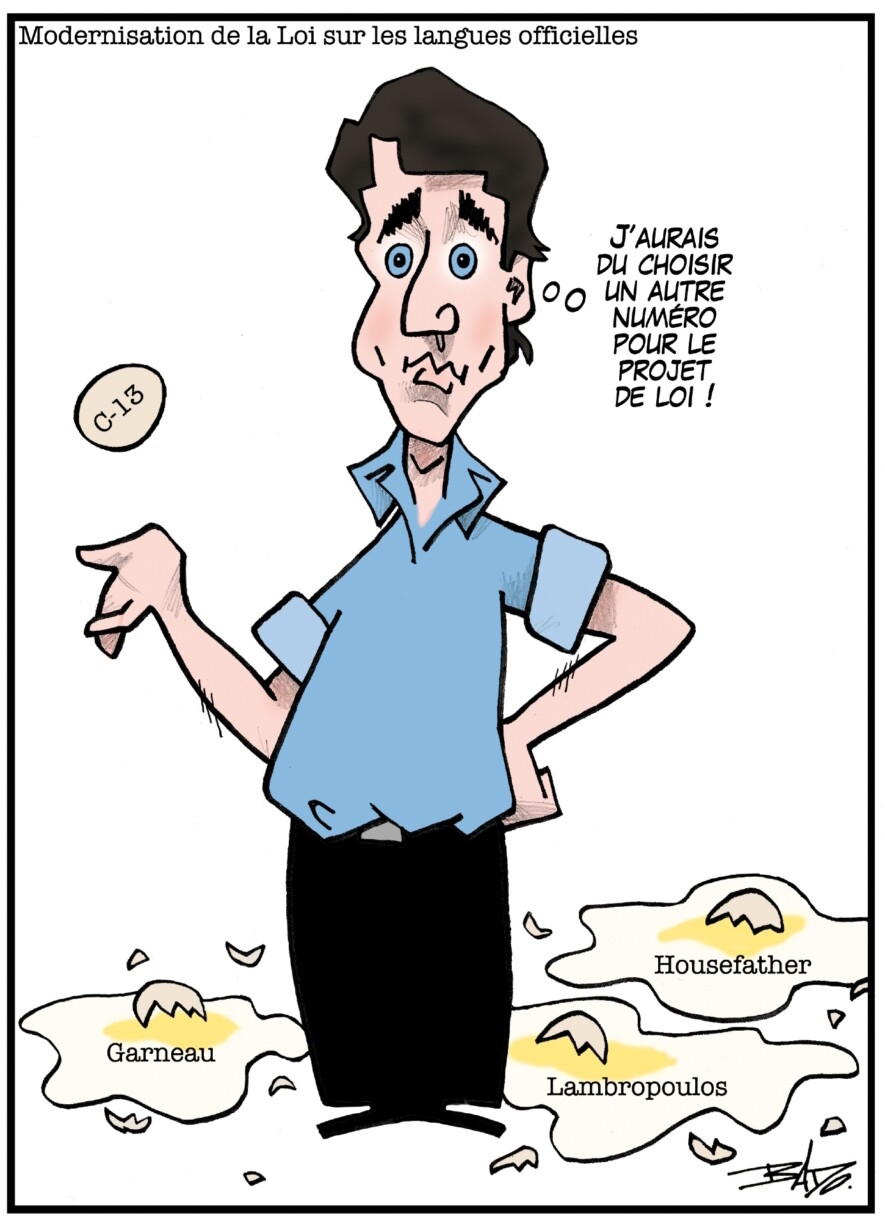

In 2019, the Government sets about modernizing the Official Languages Act. After lengthy consultations, a commitment is made to strengthen the Act in view of the disturbing situation with French in the country. Bill C-32 is tabled in 2021, but dropped on the heels of the federal election call a few months later. The matter is revived with Bill C-13, which focuses on the use of French in federally regulated private businesses. Bill C-13 receives Royal Assent in June 2023, and becomes An Act for the Substantive Equality of Canada’s Official Languages.

Tabling of the draft legislation on modernization of the Official Languages Act is delayed due to, among other things, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bill C-32, amending the Official Languages Act, is set aside when the federal election is called in August 2021. The current version of the Act dates back nearly 35 years.

Bill C-32, amending the Official Languages Act, appears to be dead, even though the new Minister of Official Languages maintains that it is one of her priorities.

Decisive changes are made to the Official Languages Act, now called Bill C-13. It highlights the fragility of French in Canada and the divergent realities of francophone minorities and Quebec’s anglophone minority despite the disapproval of certain federal MPs, including Marc Garneau, Anthony Housefather and Emmanuella Lambropoulos.