Regulation 17 and educational management: a difficult journey

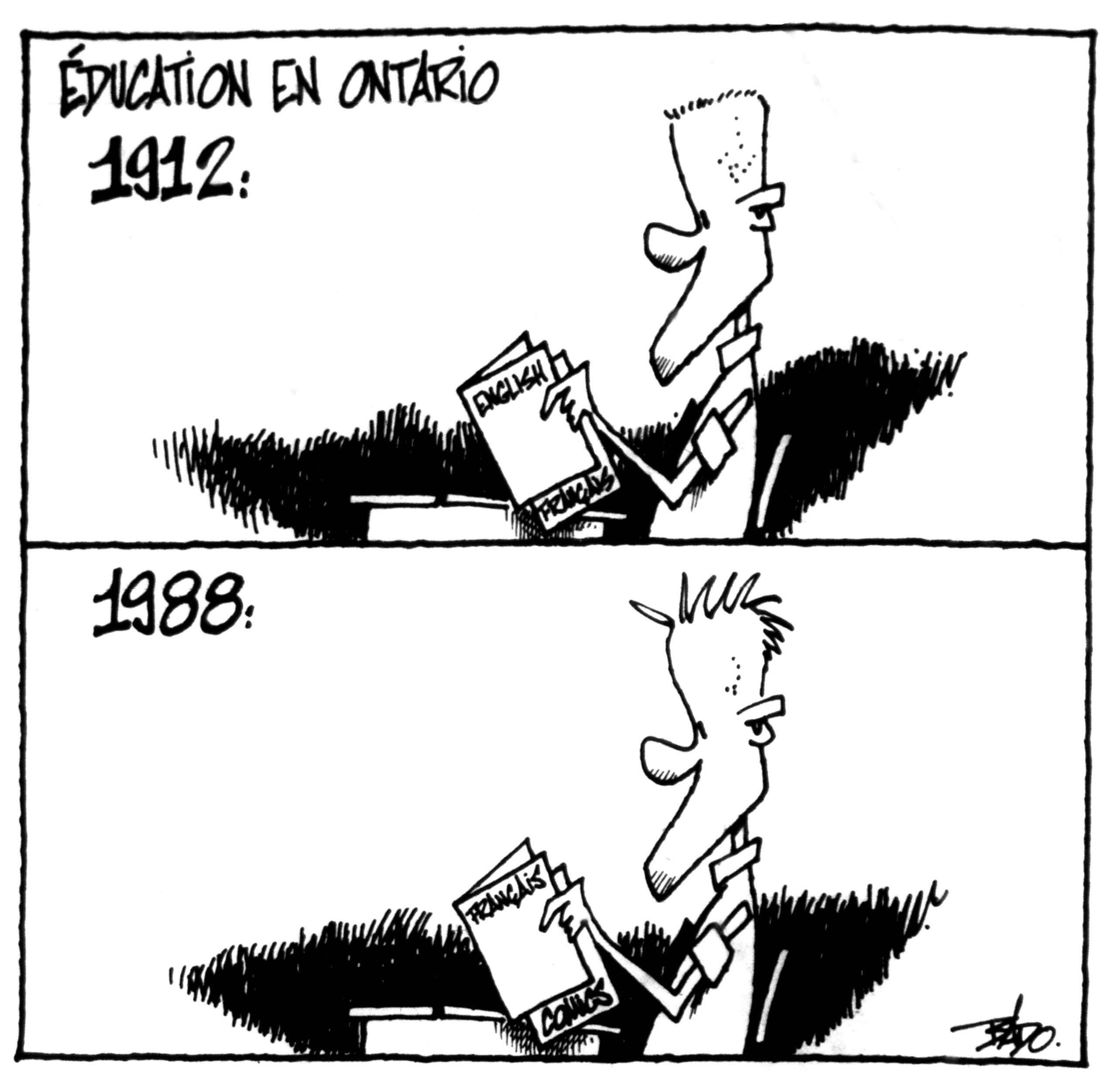

The community waged a tough battle for French-language educational rights. In 1912, the Regulation 17 crisis posed a major threat to the future of Franco-Ontarians. But they came out of it stronger, well aware of the importance of their language rights to their community’s survival. Although the Regulation was set aside for the next 15 years, the struggle was far from over.

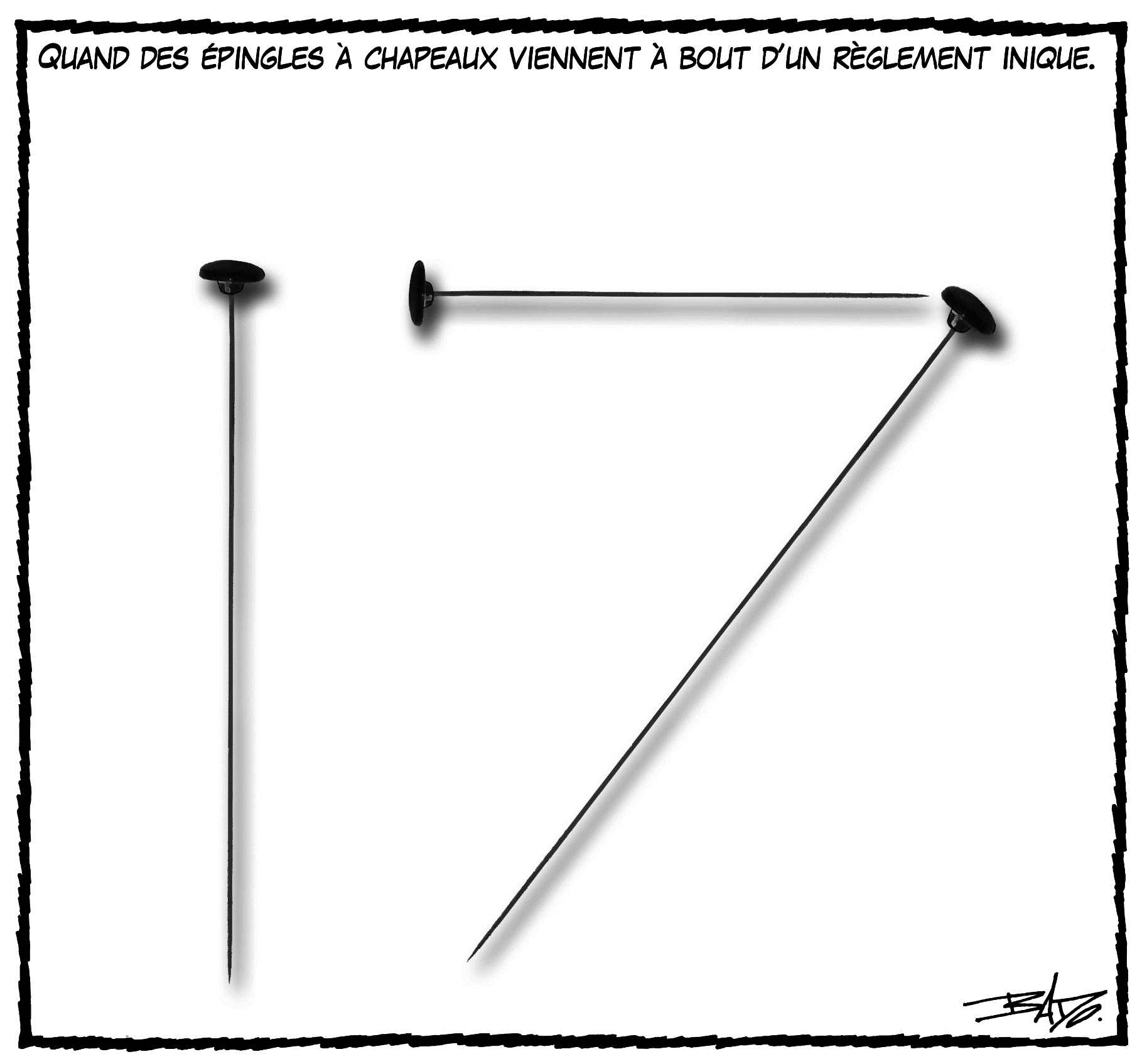

Drawing highlighting the 100th anniversary of resistance to Regulation 17 at École Guigues, in Ottawa.

In the mid-20th century, the Royal Commission on Education in Ontario (Hope Commission) released a report that focused on the need for bilingualism among Franco-Ontario’s students. The Commission also maintained that French-language education should be limited to the primary level. Once again, Franco-Ontarians fought back, convincing the Province to promptly disregard the report’s recommendations.

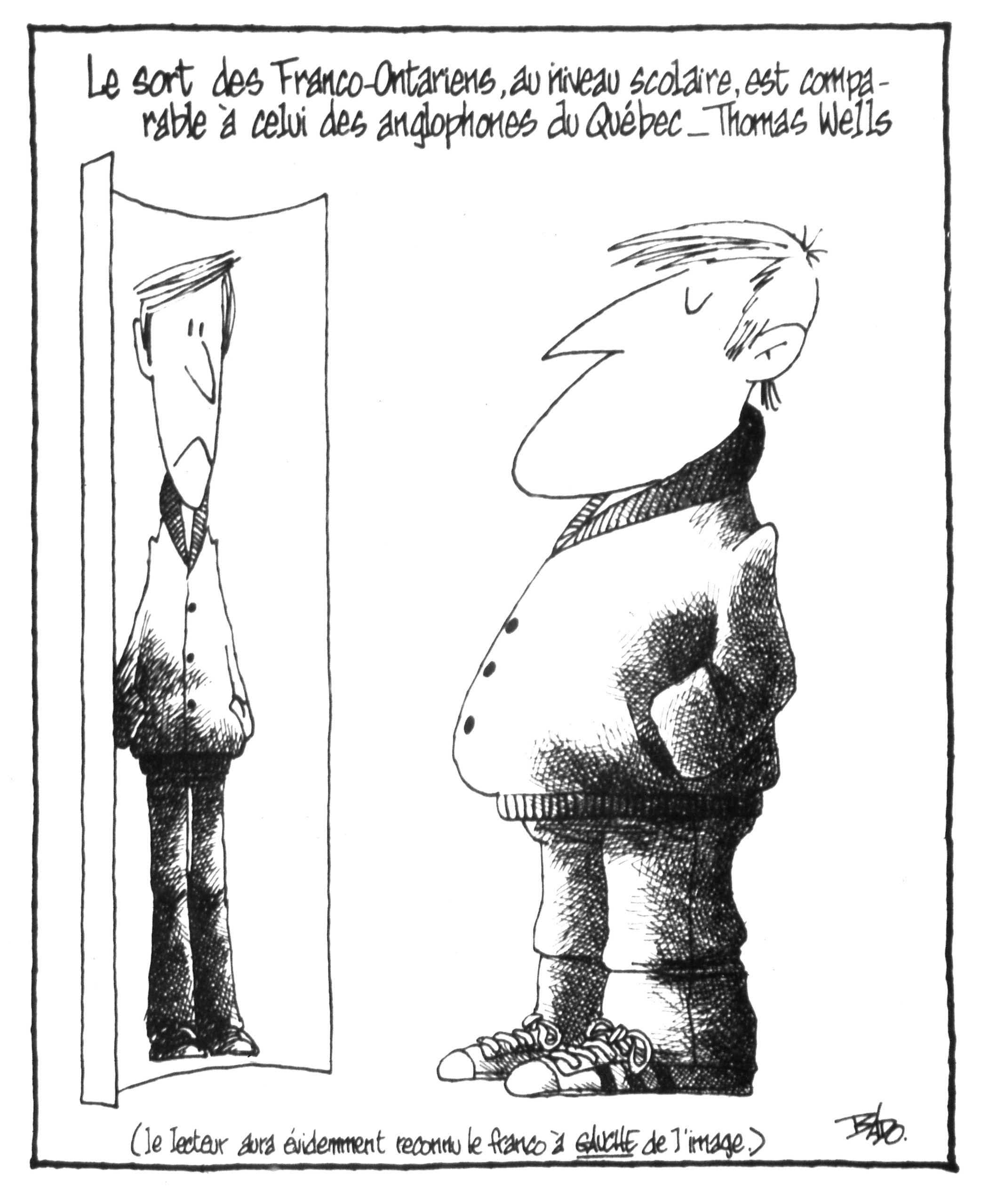

Bette Stephenson, Ontario MLA and Minister of Education from 1975 to 1987 (Conservative). After a protracted legal battle, the French-language high school Le Caron is inaugurated in Penetanguishene.

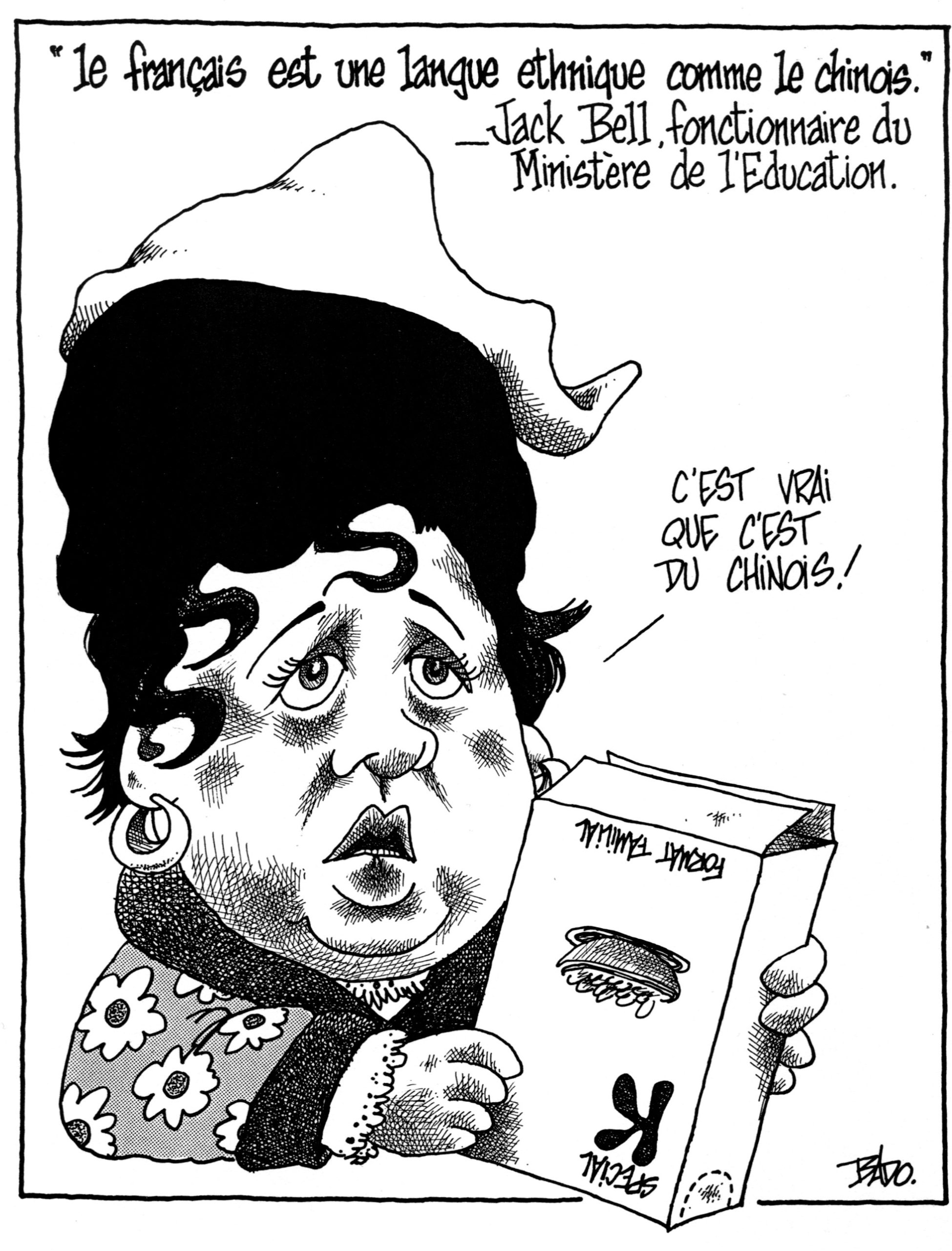

Bette Stephenson, Ontario MLA and Minister of Education from 1975 to 1987 (Conservative). As part of the secondary school and mandatory credit reforms, a Ministry of Education official stated that French is an ethnic language, like Chinese.

In 1968, the Ontario Government adopted Bill 141, opening the door to the establishment of French-language classes and schools in English majority school boards. Over the following decades, numerous educational crises erupted across Ontario, namely in Sturgeon Falls (1971) and Penetanguishene (1980). Those crises mainly affected areas where there were not enough Franco-Ontarians. They ended up forced to fight for exclusively French-language school to avoid being lumped together with bilingual schools, which would have carried a much higher risk of assimilation.

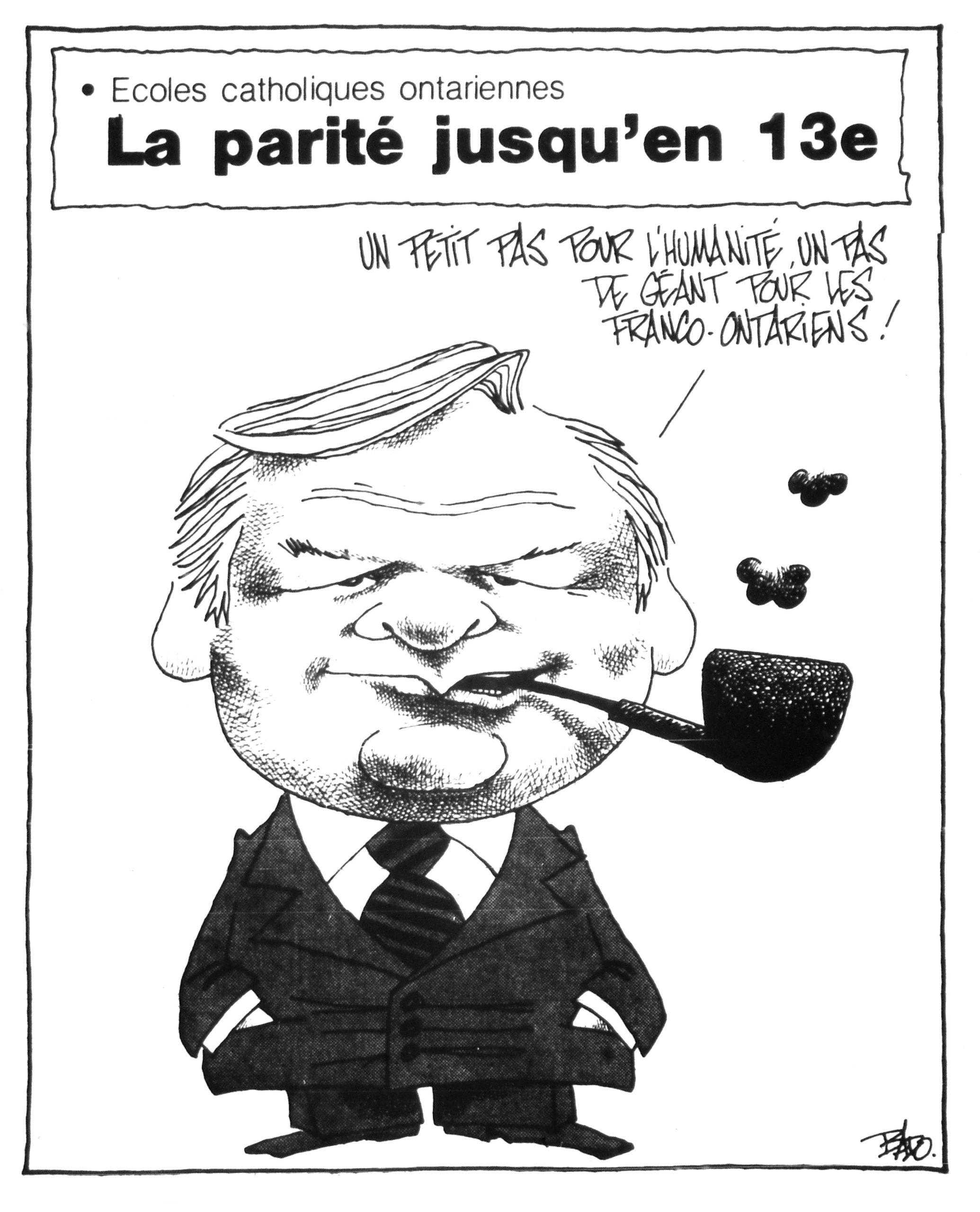

On June 12, 1984, the Ontario Government tabled draft legislation extending grants to grades 11, 12 and 13 in the province’s Catholic schools. Until then, the grants stopped at grade 10.

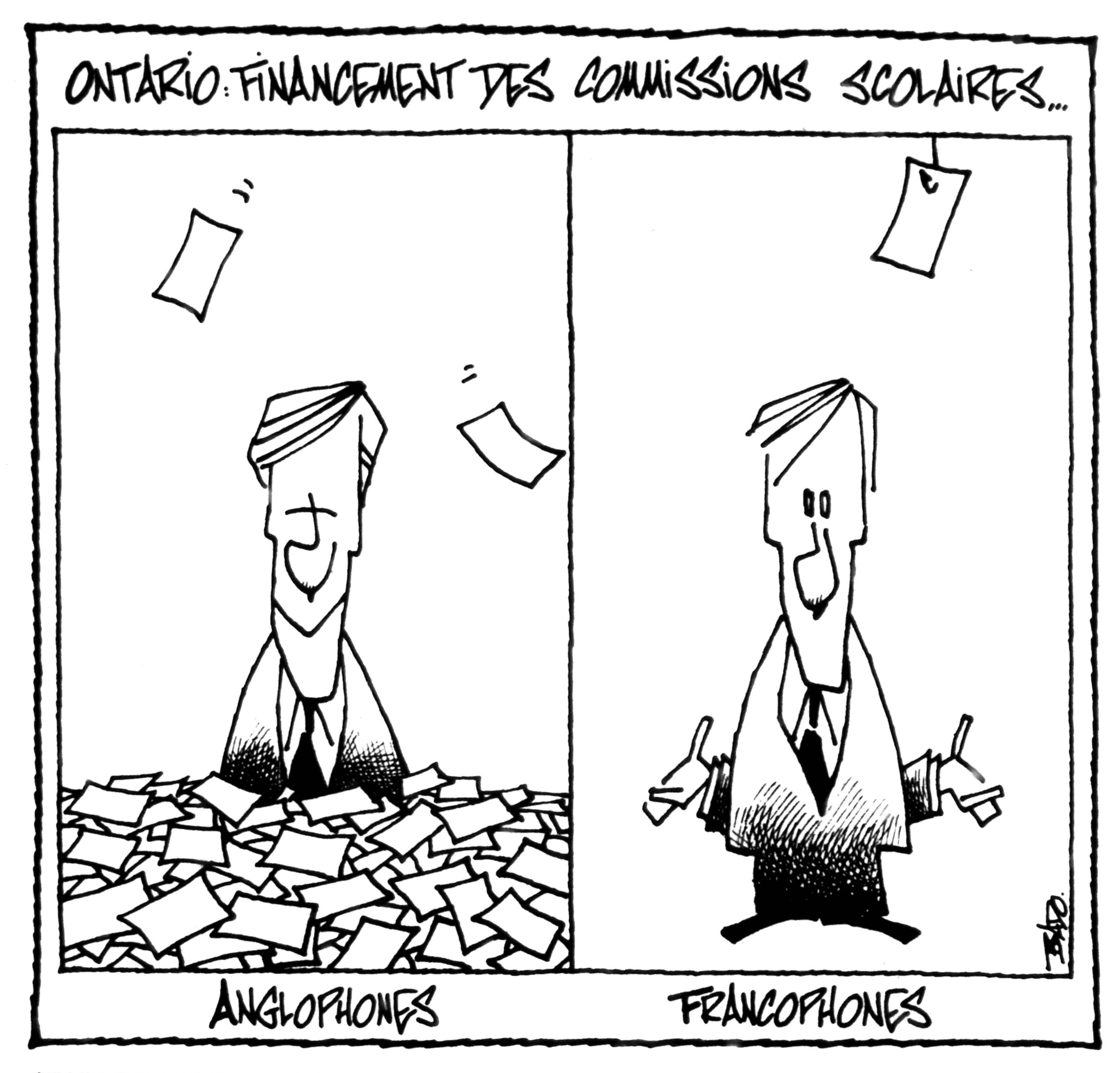

In 1982, following the enshrinement of official language minorities’ language rights into the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a number of cases were brought to court. They revolved around the clauses concerning minority language education in Canada. In 1984, the Ontario Court of Justice even found that Franco-Ontarians were entitled to greater autonomy in managing their schools. In recognition of this new reality, in 1986, the Ontario Government adopted Bill 75. The new legislation allowed the establishment of French-language sections in English-speaking majority school boards. However, there were still matters that remained unresolved, and the courts were called upon to defend the educational rights of the francophone minority.

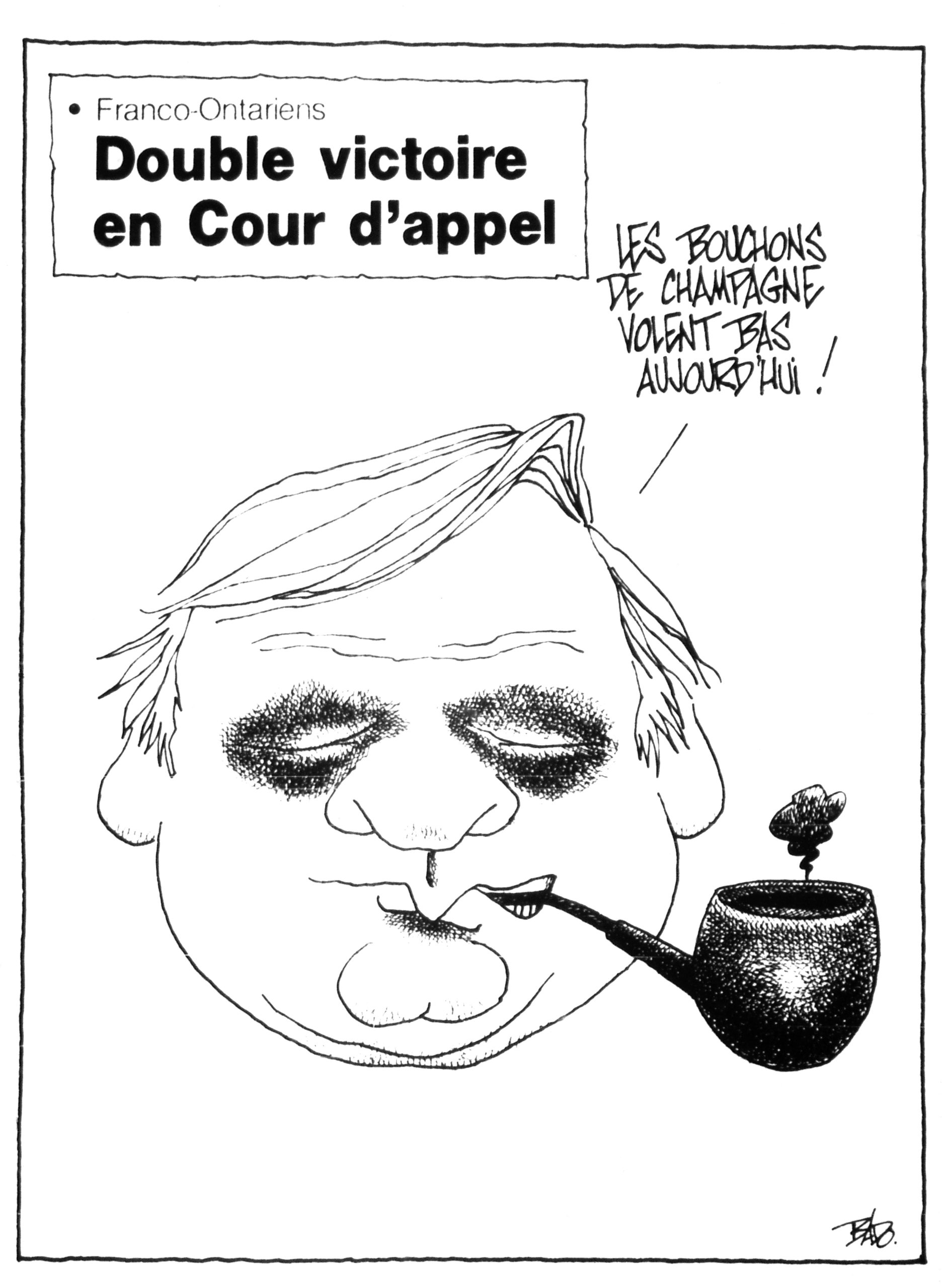

Franco-Ontarians win the Ontario Court of Appeal’s recognition of their right to education in their language and the right to manage their own schools.

The Ontario Government tries to wheedle out of the Ontario Superior Court decision on the educational representation of francophones.

It was not until late 1997 that the Ontario Government finally adopted Bill 104, giving Franco-Ontarians full authority to manage education. The new law came into effect on January 1, 1998. It also led to the establishment of 12 school boards (8 Catholic and 4 Public) throughout Ontario.

Establishment of Ontario’s first French-language school board in December 1988. It had been a long road since the adoption in 1912 of Regulation 17 restricting French-language education.

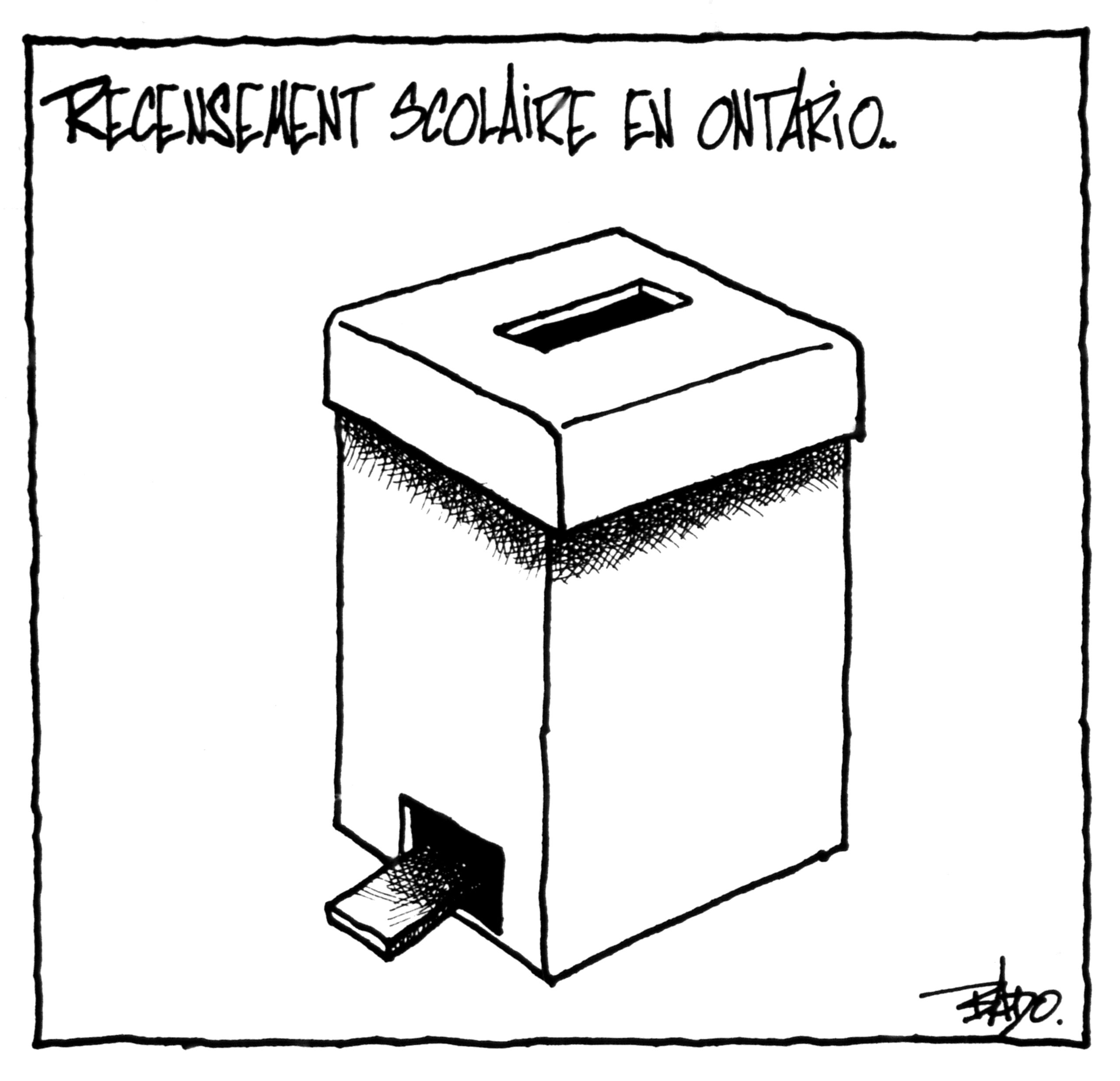

The 1991 school census skews the statistics for funding French-language school boards. Newcomers cannot identify as francophone taxpayers to increase funding for the francophone school system.