Canada’s francophone minorities

The caricaturist will occasionally comment on the plight of francophones in minority situations. Since the 1950s, their proportions have been steadily decreasing. The 1951 Census indicated that the French-speaking population outside Quebec was around 10%, the highest ever. Sixty years later, that same population stood at only 3.8%. This trend appears to be holding, given that projections by government institutions set it at 2.7% by 2036.

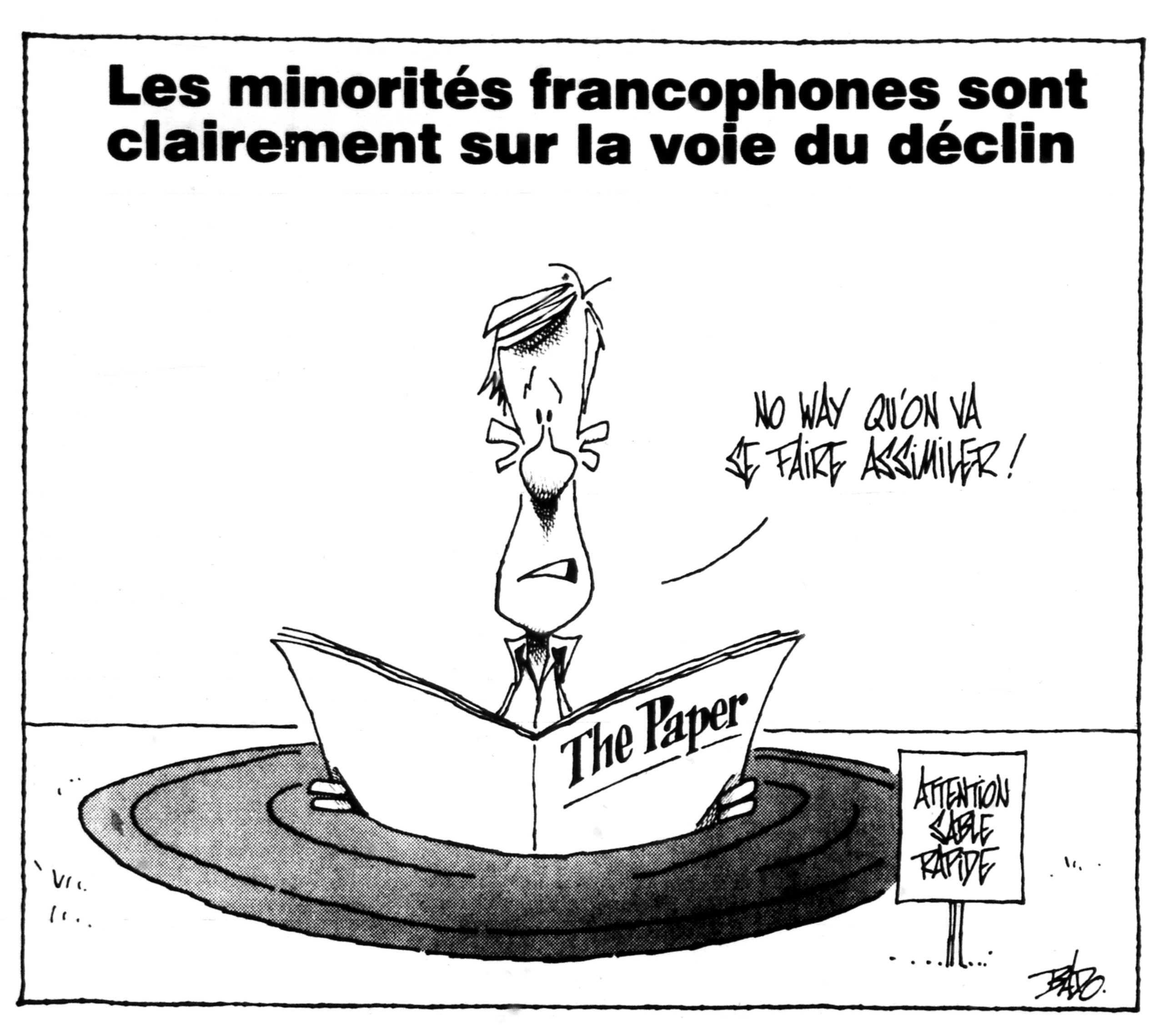

The detailed results of the 1986 Census are released. Francophones outside Quebec are losing ground. In the space of five years, their proportion fell from 4.9% to 4.5%.

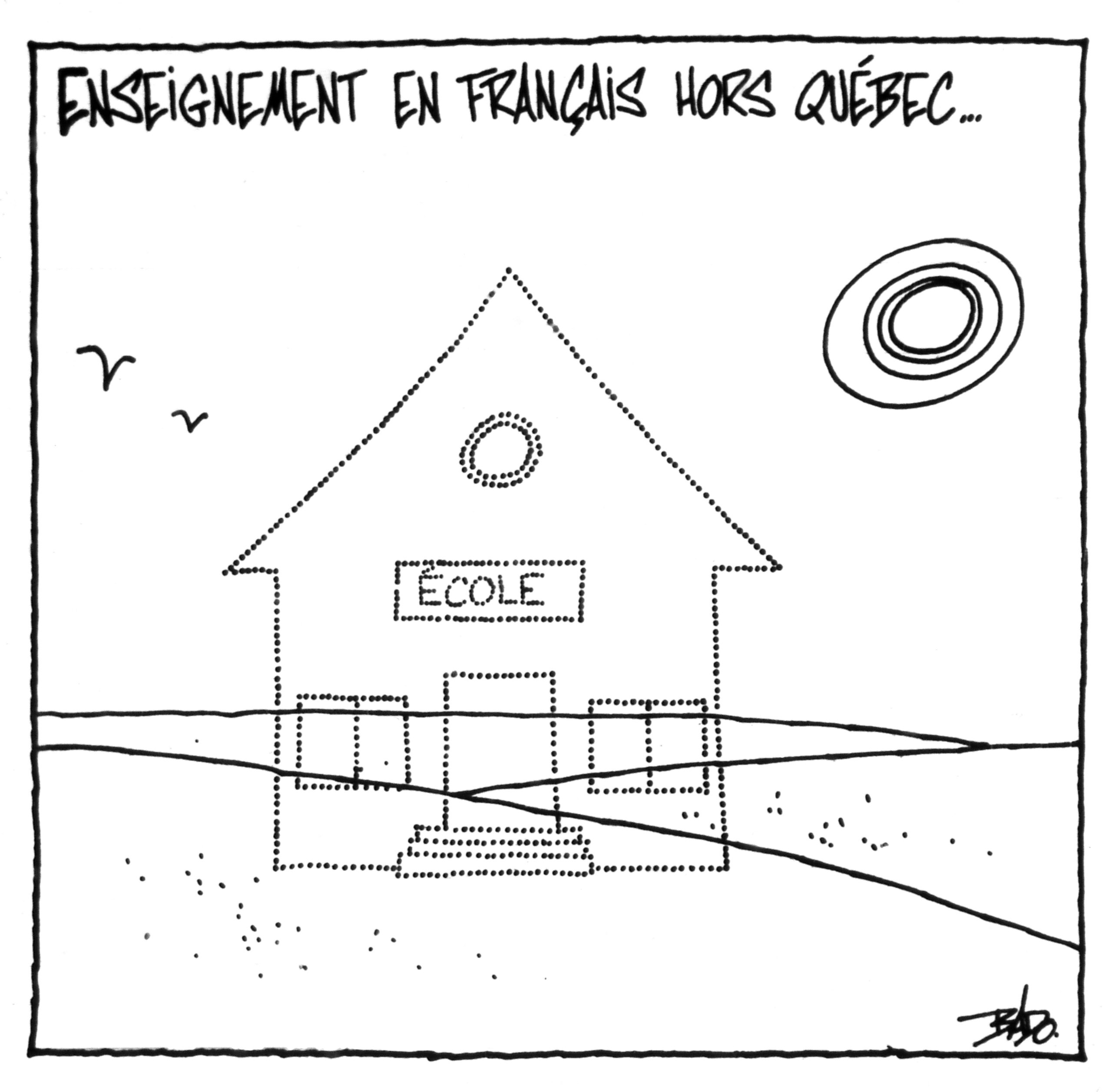

In absolute numbers, the francophone population is increasing. However, that’s happening at a much slower pace than the rest of Canada’s population. The number of francophones may be increasing, but their proportion is decreasing. That decrease is often attributed to the growing difficulty of accessing French-language education throughout the whole span of primary to university. Federal authorities take the situation seriously. Recently, the federal Minister of Official Languages, Ginette Petitpas Taylor, indicated that the census data on official languages was a source of concern, and that French is threatened in Canada, even in Quebec. As the Minister indicated, Quebec is no exception to this general declining trend, despite being the home of 84% of Canada’s francophonie.

According to a study prepared by the Commissioner of Official Languages of Canada, one out of every two young francophones outside Quebec will not receive French-language instruction guaranteed them by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The assimilation of francophones into English Canada is also a huge problem. For years, there has been a constant gap between mother tongue and language spoken at home, an alarming assimilation touching a very large proportion of francophones outside Quebec. The rate of shift in language spoken at home to English among francophones in Canada’s provinces, excluding Quebec and New Brunswick, ranges from 40% (Yukon) to 74% (Saskatchewan). This situation does not augur well for the future.

Statistics Canada releases alarming numbers on the rate of assimilation of Franco-Ontarians. In 1996, 479,000 Ontarians reported French as their mother tongue. Of those, only 287,000 reported speaking that language at home. That represents an assimilation rate of close to 40%.

The following is a quick overview of the difficult situations often encountered by those communities who periodically face threats to their language and culture.

New Brunswick

In New Brunswick, the birthplace of the former French colony that spawned the Acadian people, French has long held a preponderant place. These days, francophones account for just over 30% of the population. New Brunswick’s first Official Languages Act was passed in 1969, at the same time making the province officially bilingual. To date, it is the only one in Canada.

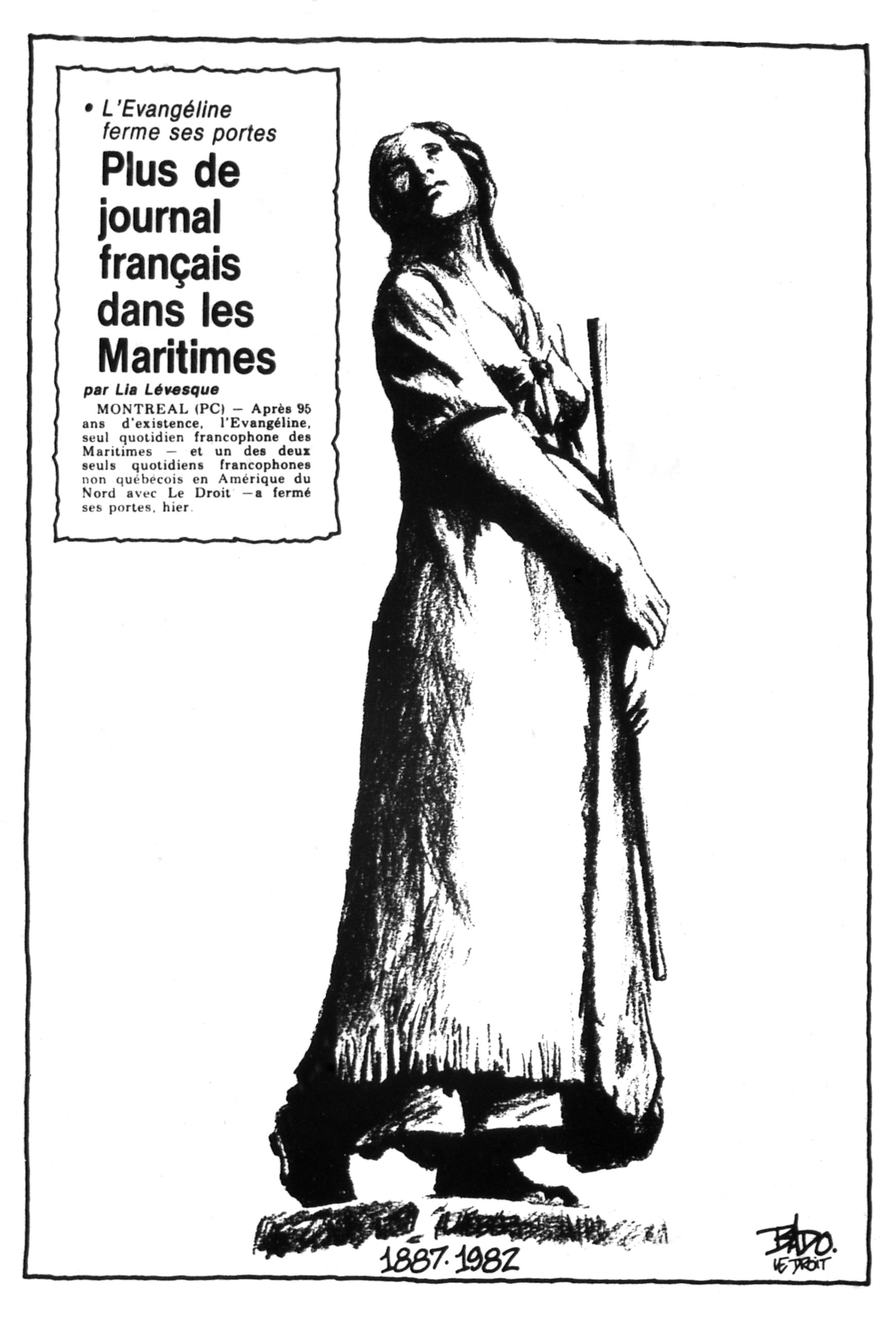

On September 27, 1982, the newspaper L’Évangéline, the only French-language daily in the Maritimes, closed its doors after 95 years in existence.

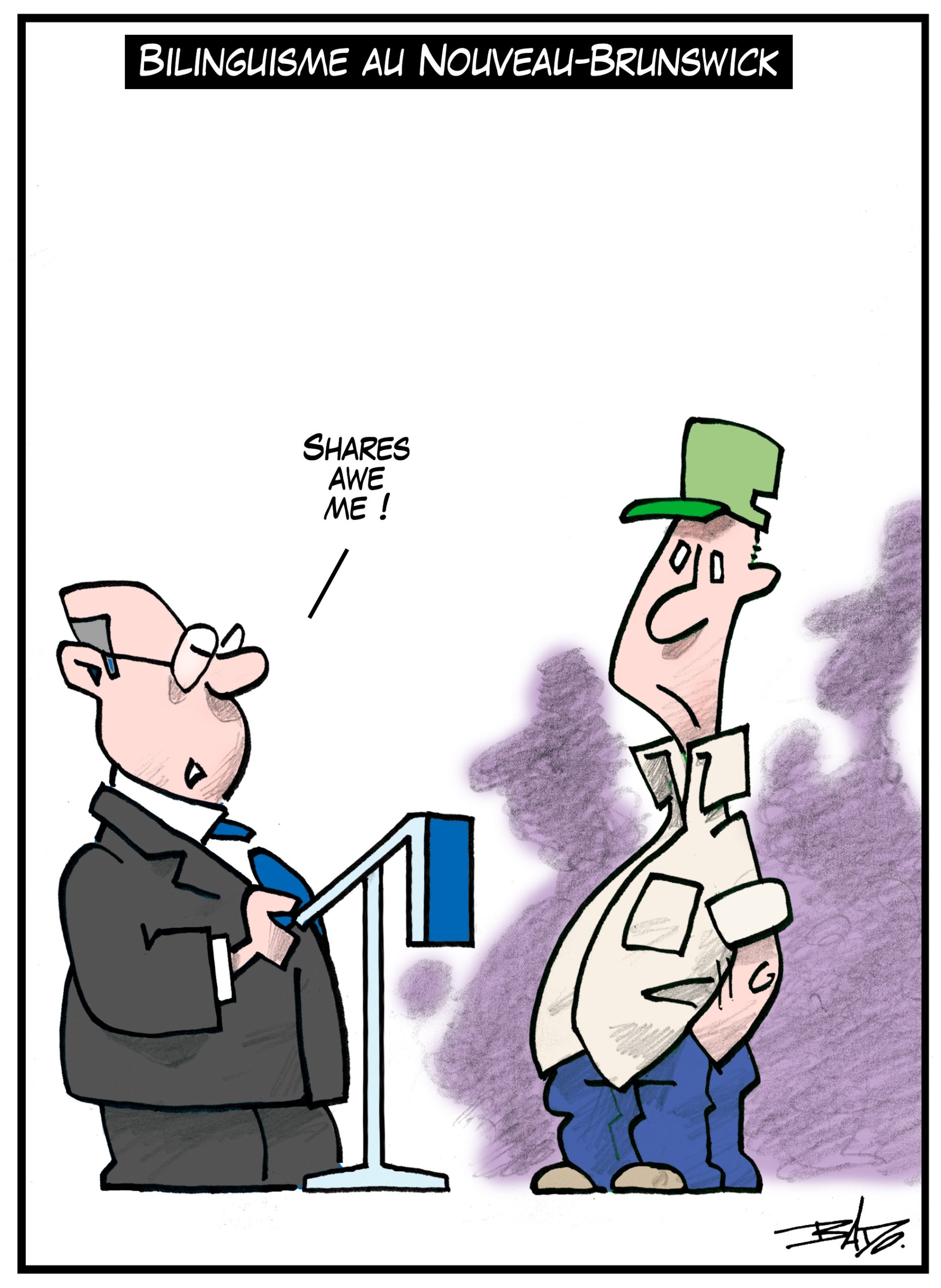

Two political parties running in the provincial elections (the Conservative Party and l’Alliance) raising the issue of the province’s bilingualism.

In more recent times, the election of the Higgs Conservative Government in 2018 ended up undermining the gains made by francophones. The Premier, who, according to the province’s Constitution, is charged with enforcing the Official Languages Act, is a former member of the Confederation of Regions Party, which is strongly opposed to bilingualism.

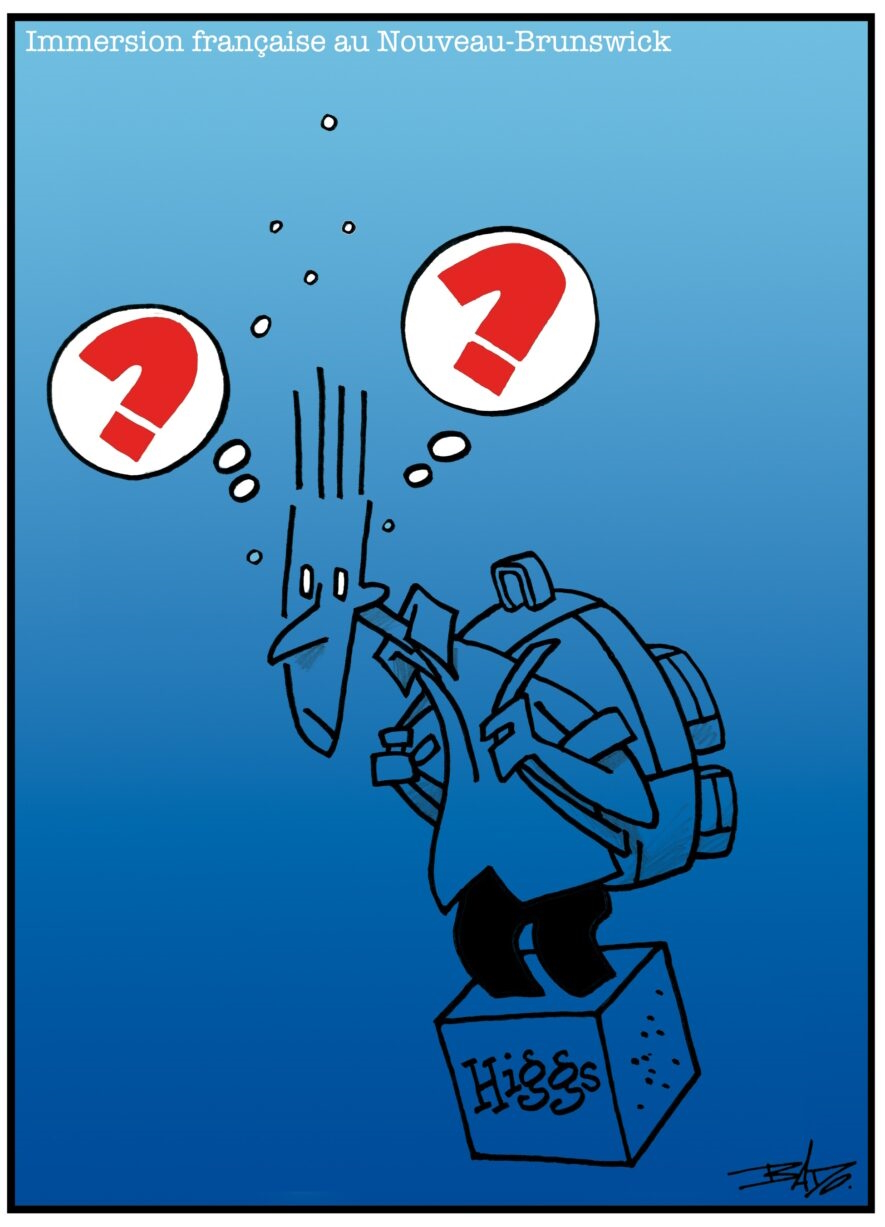

The Higgs Conservative Government calls into question the province’s French immersion program, prompting the resignation of the Minister of Education, Acadian Dominic Cardy.

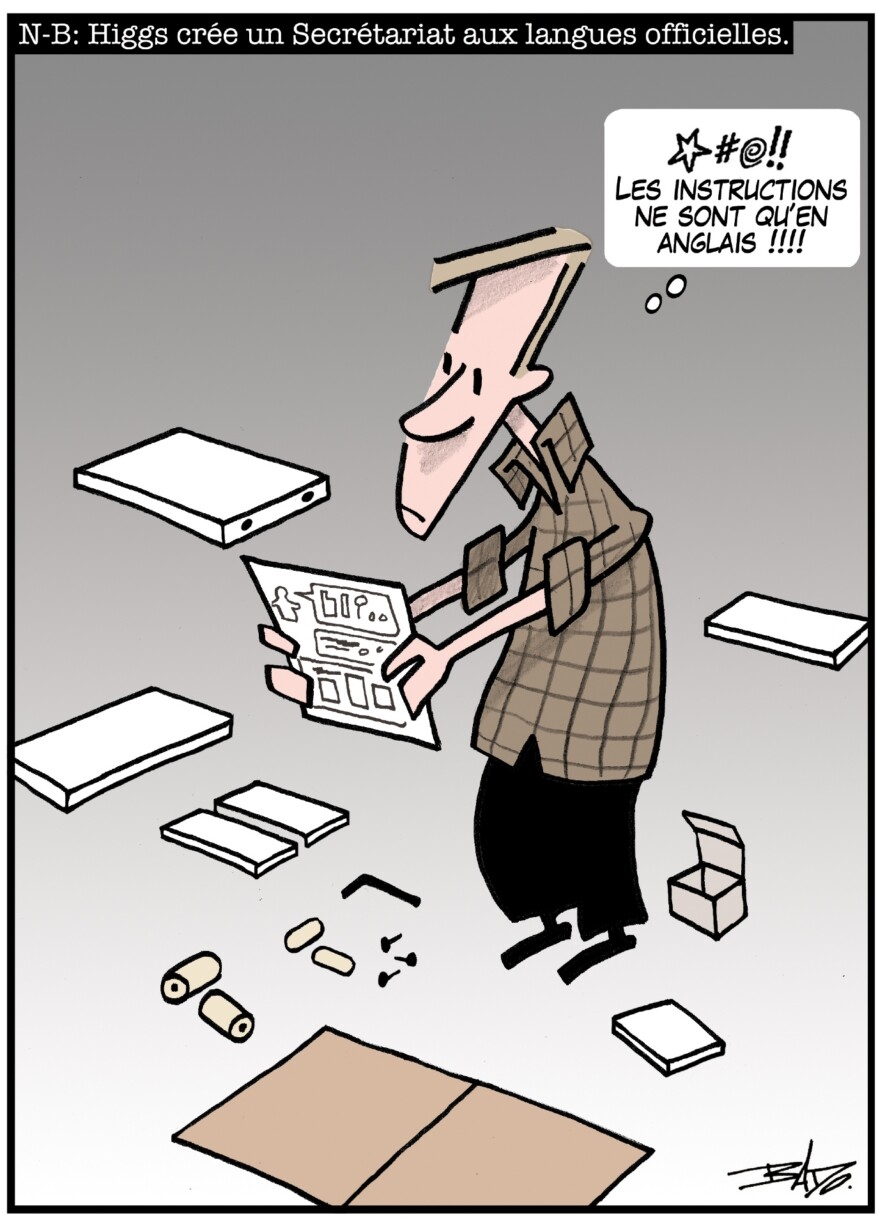

Premier Blaine Higgs, who is supposed to review New Brunswick’s Official Languages Act, ignores most of the main recommendations made by the commissioners, with the exception of the creation of an official languages secretariat.

The Maritimes

In the 19th century, Acadians living in the Nova Scotia territory were drowned out by the mass arrival of Anglophone immigrants from the United Kingdom. From that point on, Acadians were simply completely overlooked. A similar situation exists in Prince Edward Island. Today, francophones since birth in both provinces remain a tiny minority (approximately 3.5%), despite their strong sense of pride in their communities.

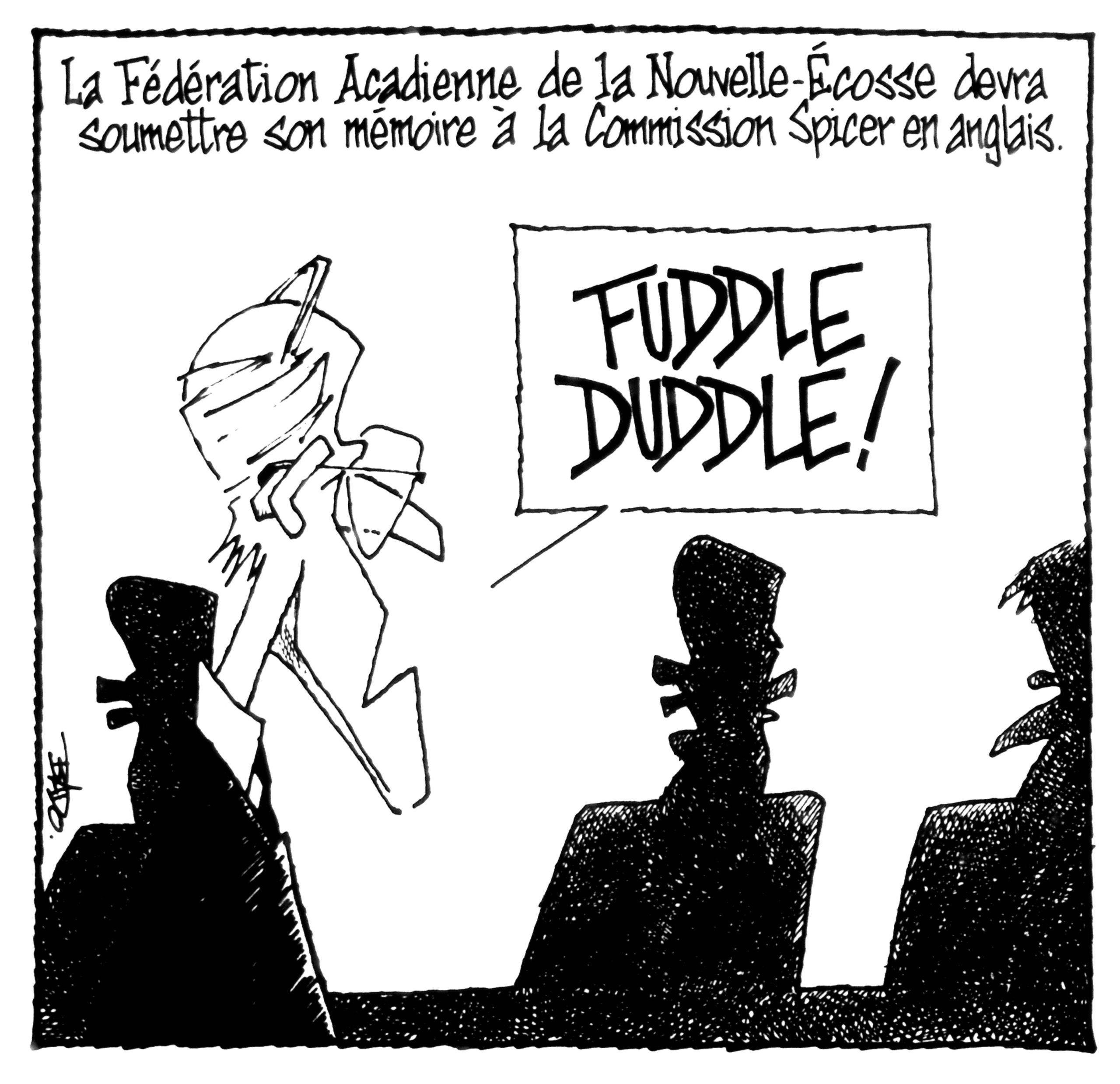

Acadians in south-western Nova Scotia and Halifax are denied the right to express themselves in French during hearings held by the Spicer Commission, a citizens’ forum on Canada’s future. The Fédération acadienne even had to submit its brief in English. The expression “fuddle duddle” refers to the swear words used by Pierre Elliot Trudeau in the House of Commons in 1971.

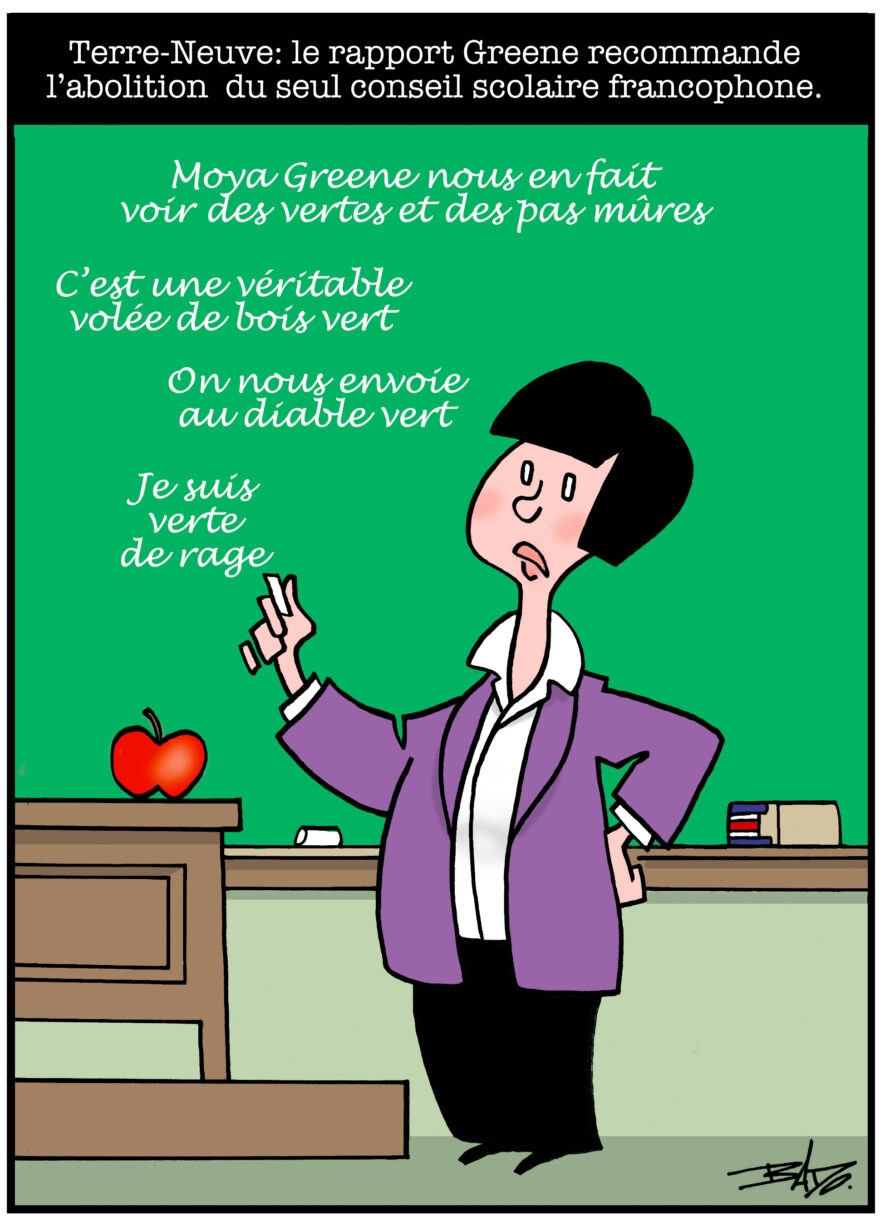

The Greene Report on the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador’s financial health is tabled. Its recommendations include the possibility of abolishing the province’s English-language and French-language school boards, which the latter see as an affront to their constitutional rights.

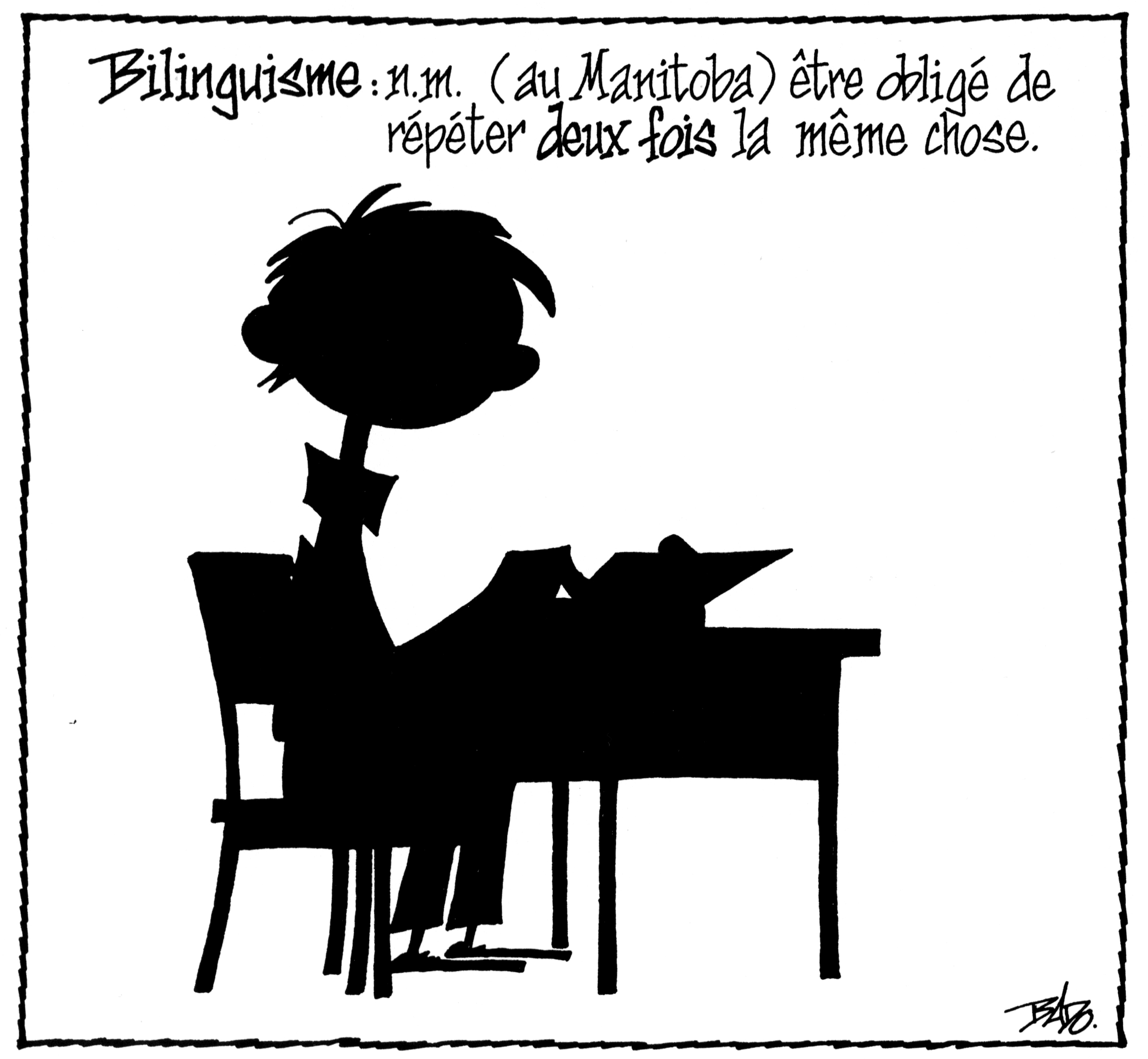

Manitoba

Manitoba is the province of the Métis people, with a mixed ancestry stemming from unions between First Nations women and French voyageurs in the 18th century. Around 1870, the province achieved perfect language duality, even enshrining constitutional guarantees in the Manitoba Act, 1870. That Act guaranteed the protection of confessional schools and official status for French in legislative and judicial bodies. In the late 19th century, those constitutional guarantees were dropped. English became the only permitted language of instruction, and French lost its official status.

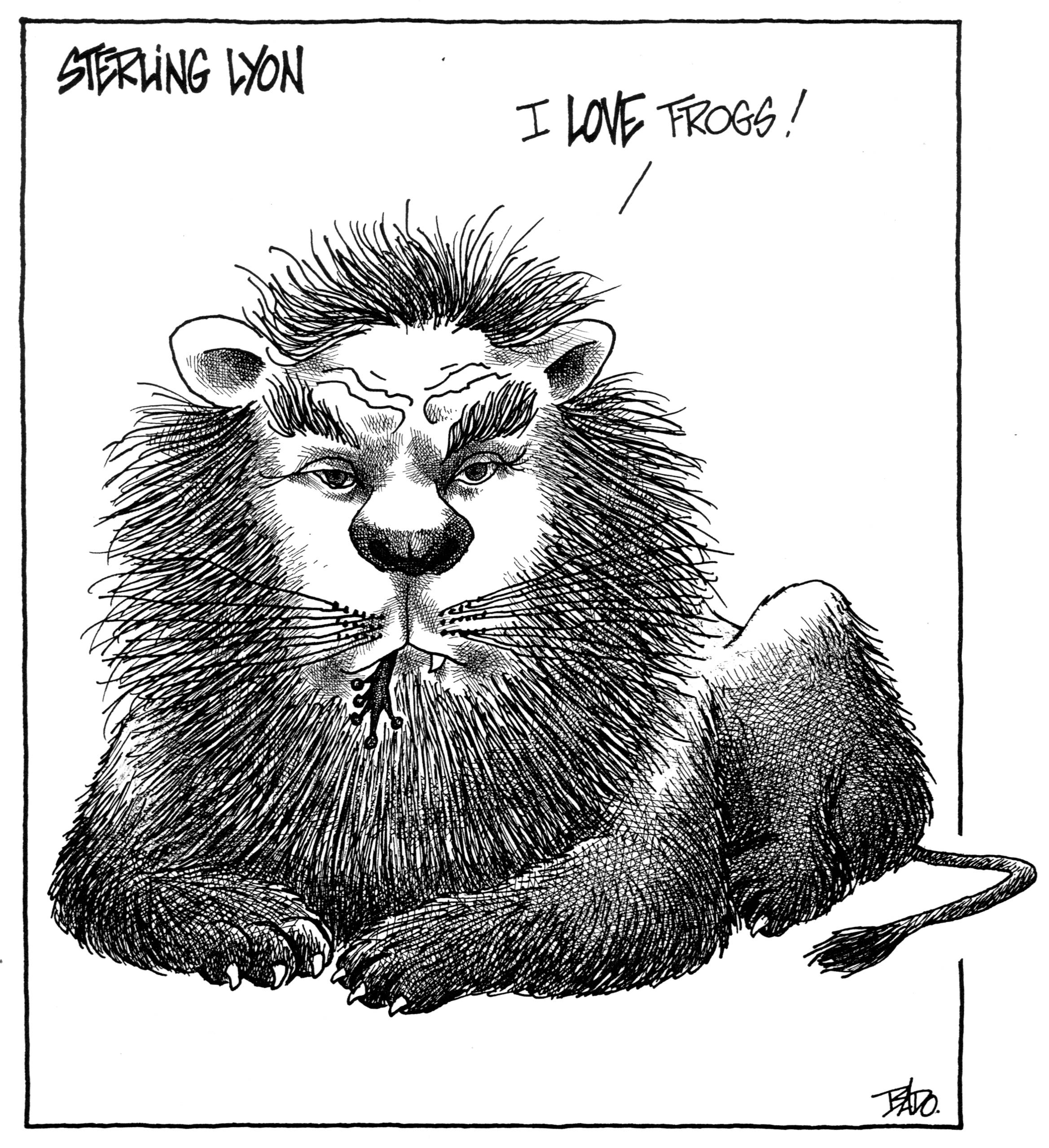

Manitoba’s Conservative opposition leader Sterling Lyon fighting tooth and nail against the constitutional recognition of Franco-Manitobans’ language rights.

The Supreme Court of Canada forces the Government of Manitoba to translate more government documents into French. The decision is greeted with enthusiasm by Franco-Manitobans.

It was not until 1970, when the winds of change began to blow for francophone minorities in Canada, that French became recognized as a language of instruction. Despite recent legislative gains, Manitoba’s francophones are losing ground, accounting for slightly less than 3% of the population.

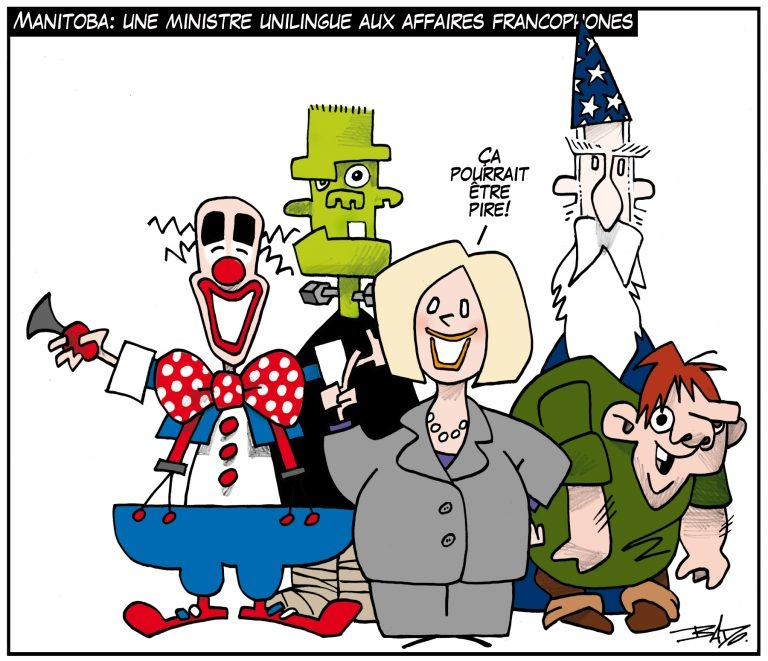

The Manitoba government appoints unilingual Rochelle Squires as Minister responsible for the province’s francophone affairs. Ms. Squires was elected in a constituency with a high proportion of francophones.

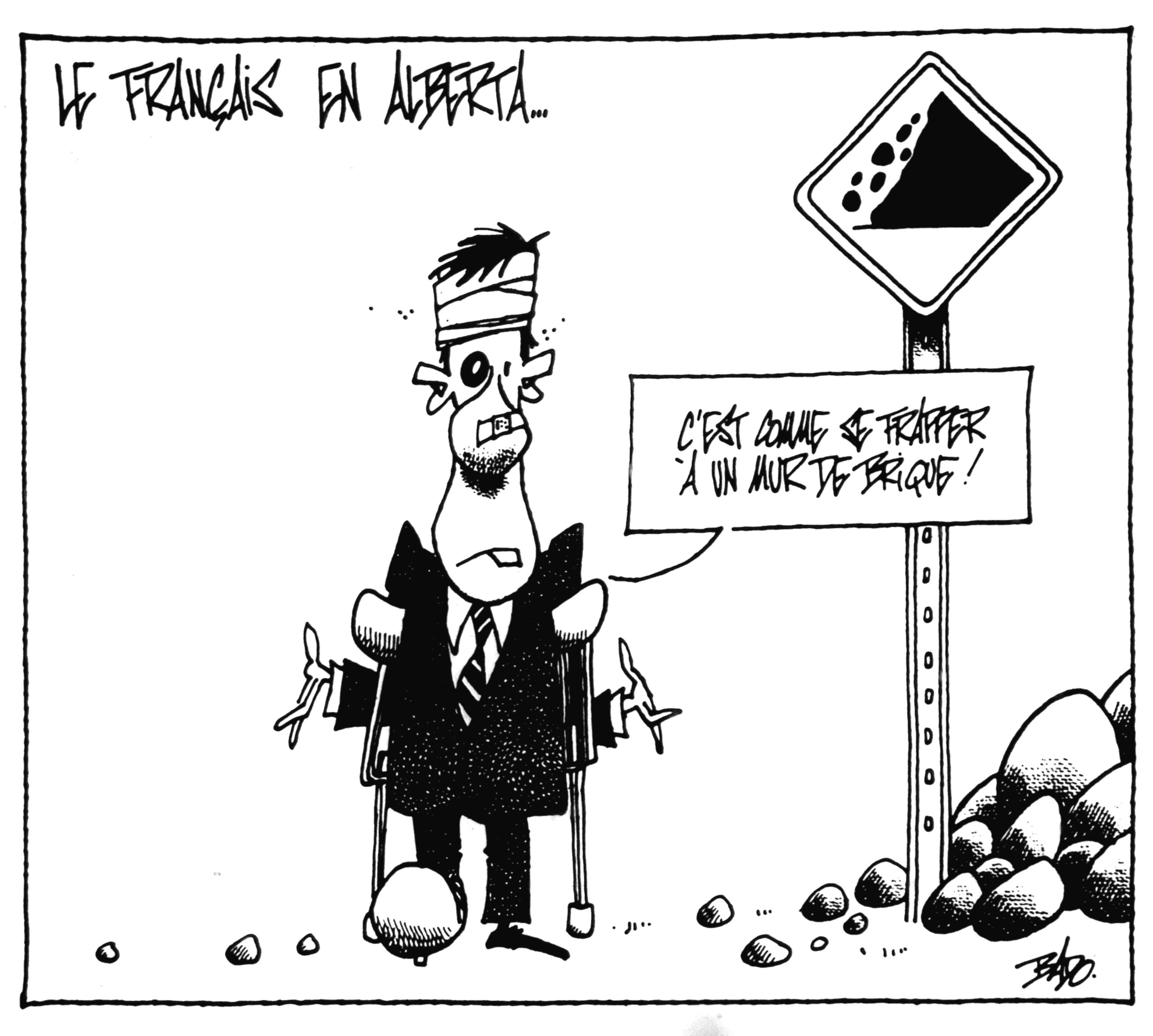

Alberta

Alberta’s first settlers were francophones. In the late 18th century, during the reign of the fur trade run by the Hudson’s Bay Company, French was the majority language in the territory. There are still numerous toponyms associated with that francophone presence. In the late 19th century, the Legislative Assembly of Alberta passed legislation making English the only language of instruction in the province. Even so, a network of French schools managed to develop, managed by the Association canadienne-française de l’Alberta. Today, francophones account for a mere 2% of the population.

David Carter, Speaker of Alberta’s Legislative Assembly, declares that the members do not have the legal right to speak French in the House after member Léo Paquette asks a question in French.