Bilingualism in Ontario

For years, many Franco-Ontarians have dreamed of an officially bilingual Ontario. It is important to remember that the French presence in the province goes back more than 400 years, since Champlain arrived there in 1615 to explore the territory and develop relationships with the Indigenous communities. Over time, as English-speakers became the overwhelming majority, Canada’s English elites introduced policies aimed at assimilating the francophones. The most flagrant demonstration of that was Regulation 17 prohibiting French-language education in Ontario schools. This crisis triggered the community, which ended up waging several battles throughout the 20th century to have their rights recognized.

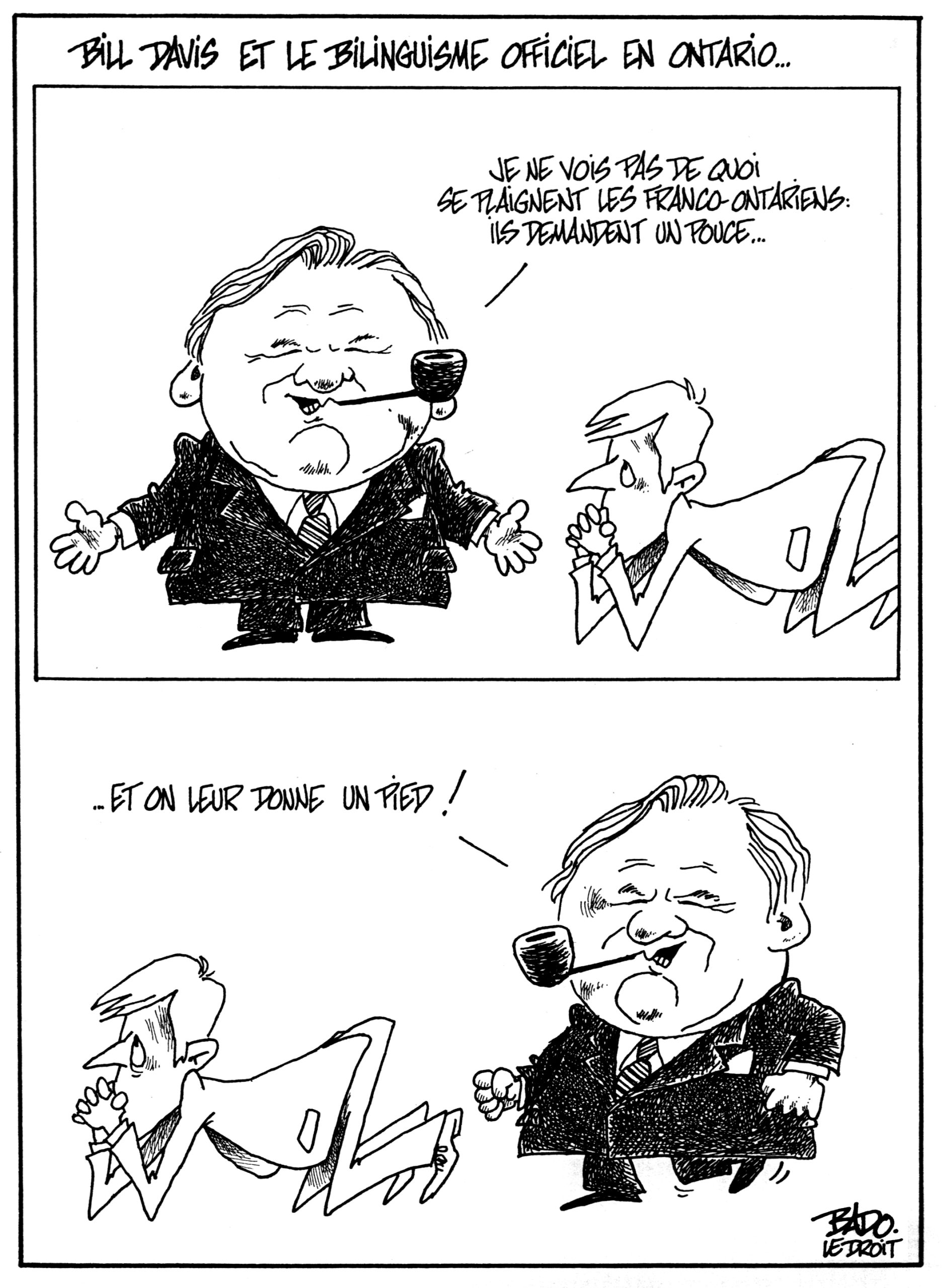

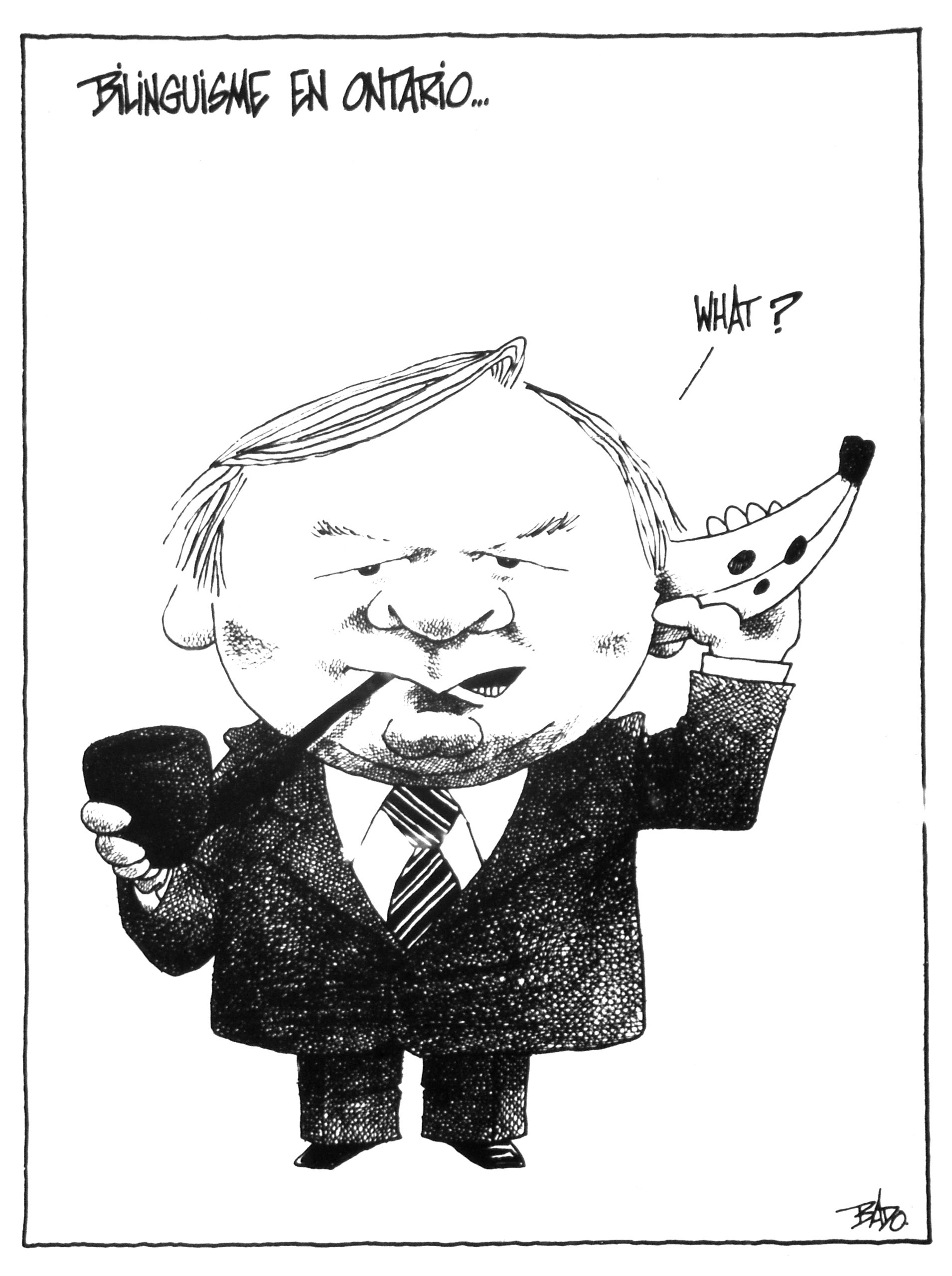

Bill Davis, Ontario’s Premier from 1971 to 1985 (Conservative). Open to the notion of legislation on French-language services, he changed his mind and opted instead for increased services rather than legislation on bilingualism.

Bill Davis, Ontario’s Premier from 1971 to 1985 (Conservative), turns a deaf ear to the demands of Franco-Ontarians.

The Regulation 17 crisis also gave rise to institutions leading the charge in defence of francophone rights. Those included the Le Droit newspaper and the Ordre de Jacques‑Cartier. Those institutions, created in Ontario, fought for more and more rights for francophones in the province and the rest of the country.

Elections in Ontario – the three parties face off on topics of concern to Franco-Ontarians: Larry Grossman (Conservative), David Peterson (Liberal) and Bob Rae (NDP).

Conservative MLA Don Cousens stands to object to the use of French by Jean Poirier, Deputy Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario.

In the 1960s, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1963‑1969) recommended official bilingualism for Ontario and New Brunswick. Unfortunately, that recommendation was only adopted by New Brunswick. In 1969, it became the first (and only) officially bilingual province in Canada. At the Constitutional Conference held in Victoria in 1971, the possibility of an officially bilingual Ontario was still on the table.

On January 29, 1990, Sault-Sainte-Marie City Council passes a resolution making it a unilingual English city.

Several Ontario cities, including Sault-Sainte-Marie and Thunder Bay, declare themselves unilingual anglophone. Many Ontarians support the move.

At that Conference, the Government of Ontario appeared to be somewhat amenable to the notion of bilingualism, which would have greatly facilitated talks with Quebec. But Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa’s withdrawal from this attempted constitutional agreement clipped the wings of Ontario’s bilingualism. The idea was dropped shortly thereafter.

On June 16, 2008, the Township of Russell, in eastern Ontario, enact a bylaw requiring bilingual signage within its territory. That sparks fights between the two language factions, fueled by francophobe militant Howard Galganov.

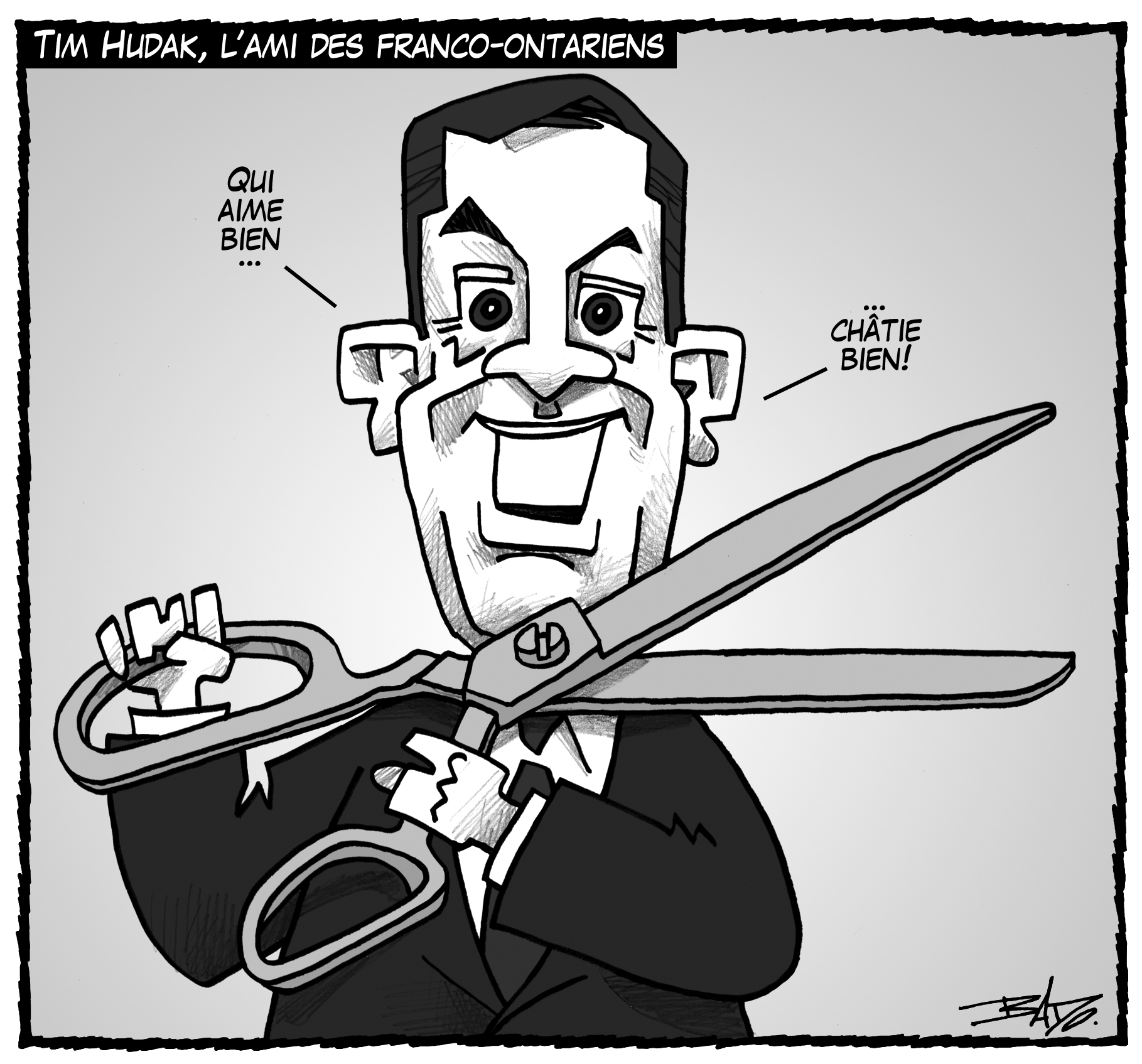

During the 2014 provincial election, Ontario Conservative Leader Tim Hudak promises to cut back public sector jobs.

Created in 1975, the Fédération des francophones hors Québec (which would become the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadiennes du Canada) called for bilingualism in Ontario and Manitoba. It also demanded a francophone-anglophone parity Senate and recognition of cultural duality, among other things.

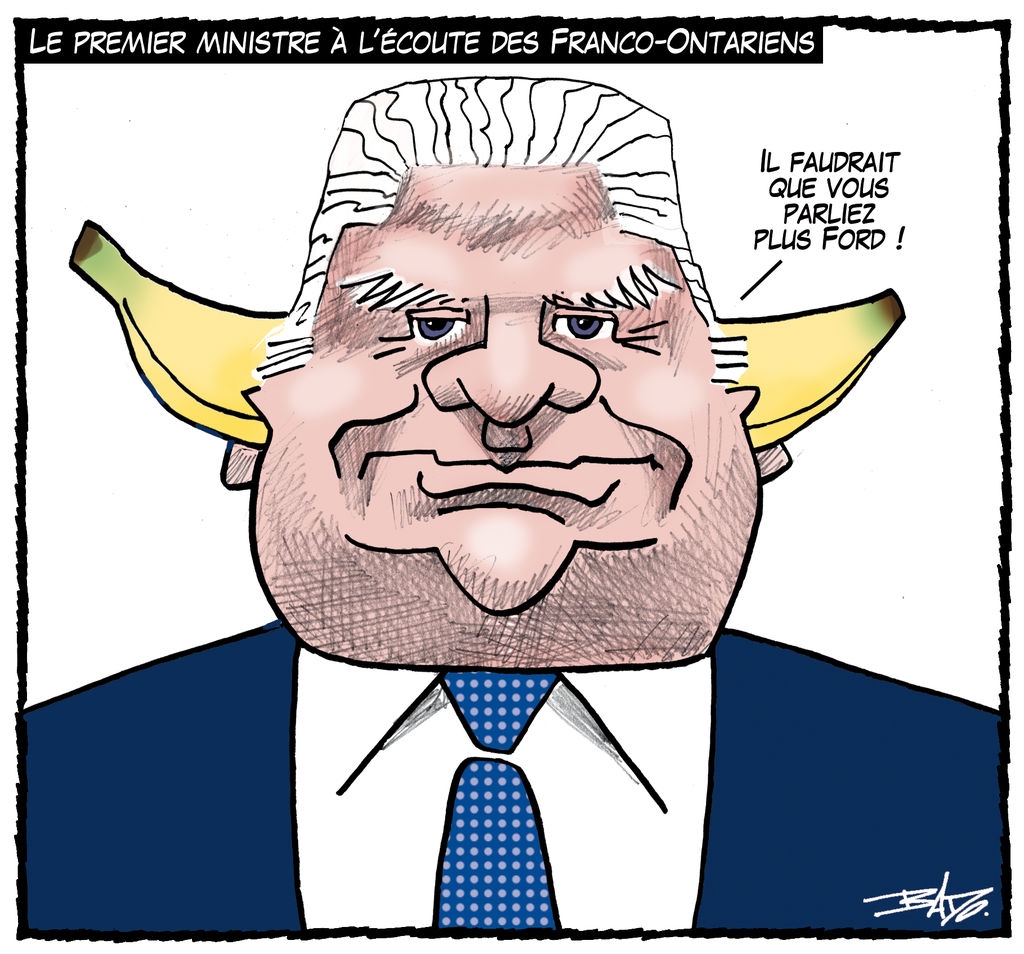

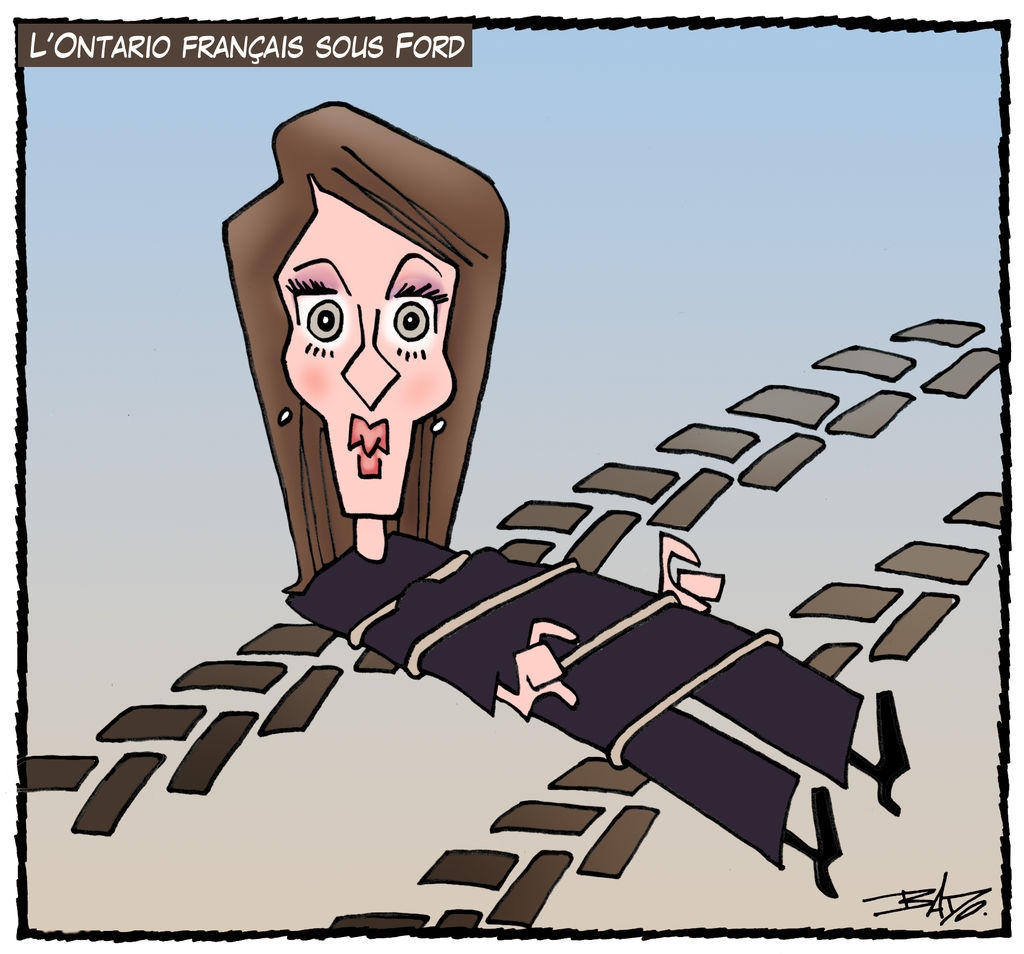

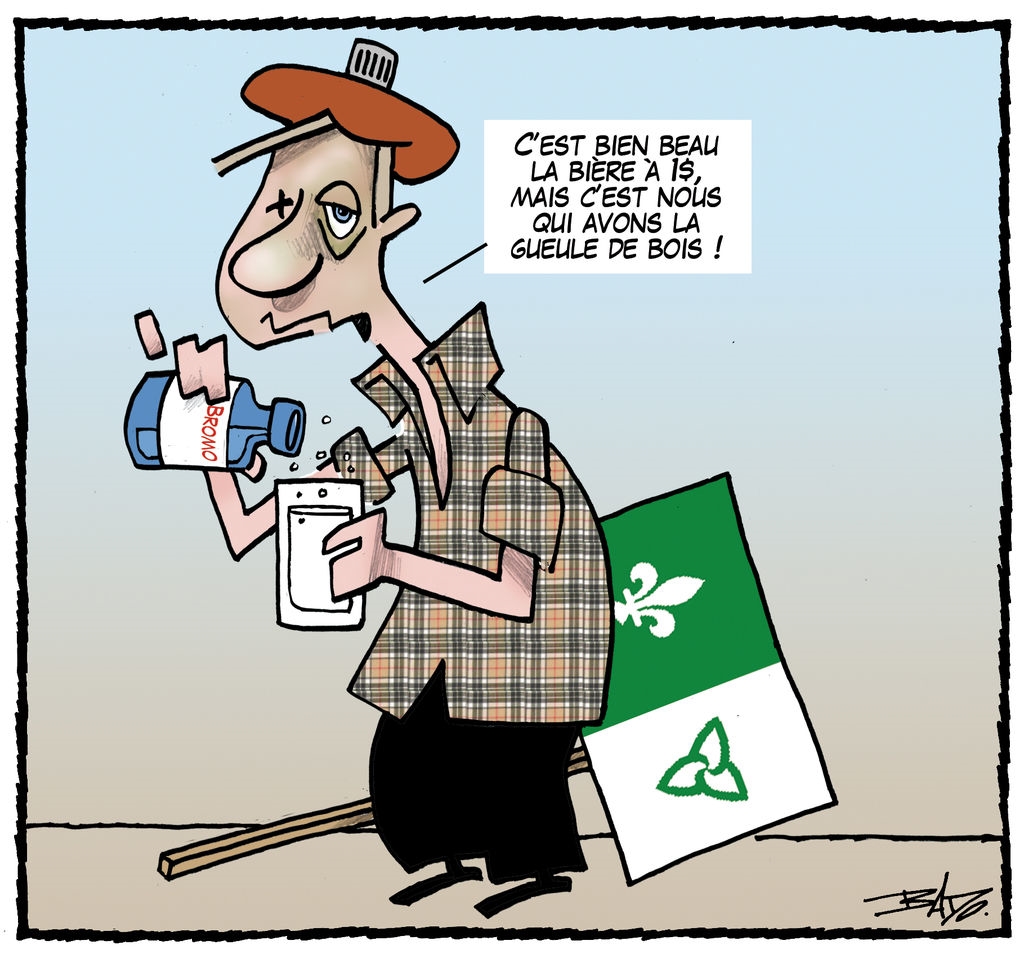

The awakening of the Franco-Ontarian community after the economic announcement by the Doug Ford government shutting down the Université de l’Ontario français and the position of French-Language Services Commissioner. We remember that one of Ford’s promises during the election was dollar beer.

The repatriation of Canada’s Constitution in 1982 once and for all closed the debate on Ontario’s bilingualism, although it provided some protection to language minorities regarding education. All in all, historians agree that it would have been quite difficult to formalize bilingualism in a province where francophones have never represented more than 8% of the population.

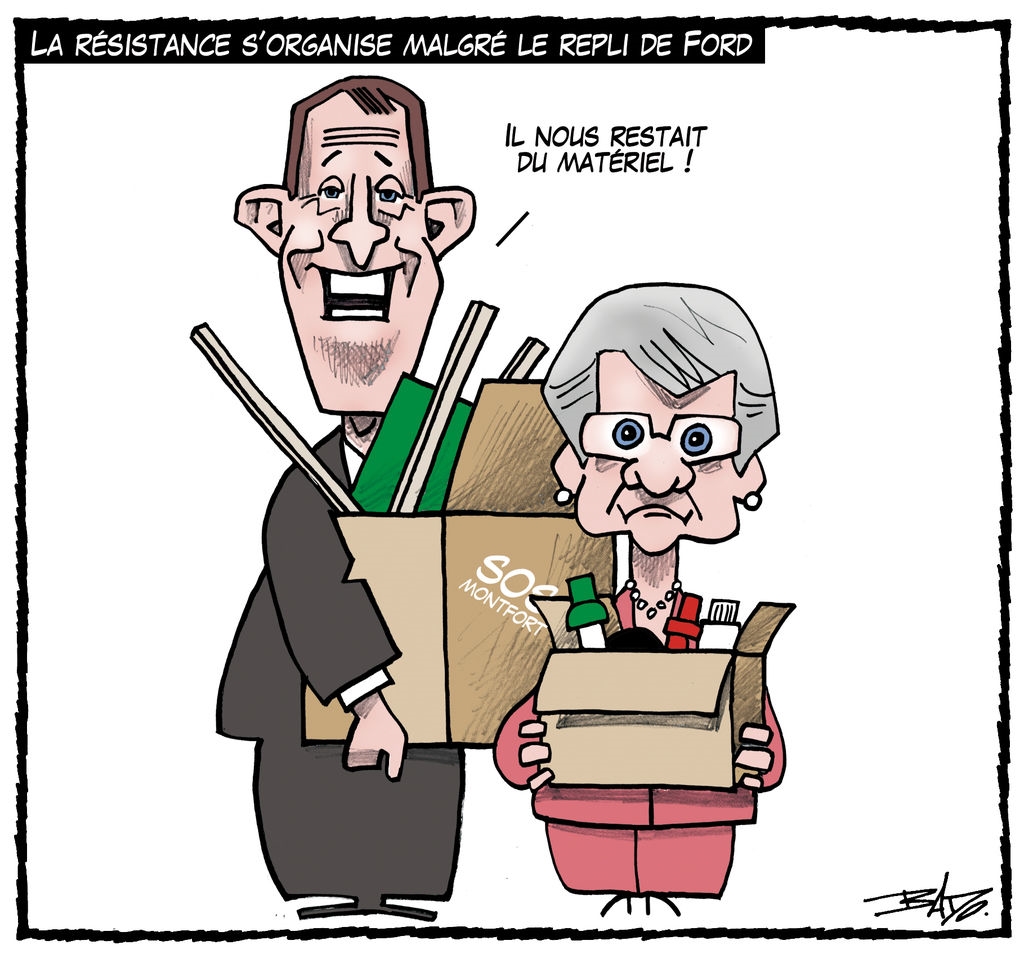

The Franco-Ontarian community preparing to protest the Ford government’s cutbacks. The figureheads in Franco-Ontarians’ major battles, Bernard Grandmaître and Gisèle Lalonde, pulling out their combat gear.