Doing it for the Kids

Around the time migrant Icelanders began to reflect more deeply on their shared history, deep concern over Icelandic language learning among the younger generations began to grow. Ensuring that children maintained good language skills was vital to help preserve the Icelandic language in North America. Publications aimed at children developed as an obvious solution to this problem.

The first Icelandic magazine for children published in North America was aimed at children only indirectly. In 1897, Björn B. Jónsson launched Kennarinn, a monthly magazine for Icelandic Sunday School and homeschooling teachers. Kennarinn provided them with both religious and Icelandic-language teaching materials. It was originally published in Minneota, Minnesota but moved to Winnipeg in 1902 when Rev. Niels Steingrímur Thorláksson took over as editor.

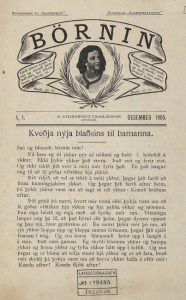

Kennarinn’s final issue appeared in October 1905. A short three-issue run of its successor, Börnin, followed. Then, in March 1908, Rev. Niels launched the new bi-weekly magazine Framtíðin, which was aimed directly at young readers. It was again religious in theme but also emphasized the need to uphold a sense of Icelandic cultural identity. Its contents included poems, stories, short essays, biographical sketches, and games. Framtíðin lasted just under two years.

Gytha Hurst, daughter of short story writer Guðrún H. Finnsdóttir and poet and printer Gísli Jónsson, recalls how she learned Icelandic. Enjoy this audio clip with an English transcript.

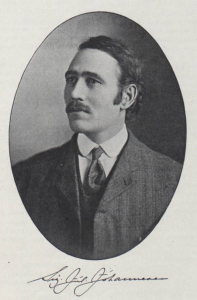

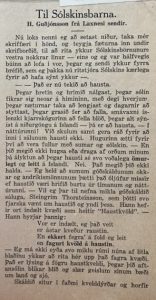

The most impactful Icelandic-language children’s magazine published in Manitoba was Sólskin. The first issue of Sólskin appeared on October 7, 1915. It was published as a part of Lögberg that children could clip out and fold to form a miniature four-page newspaper. Sólskin’s creator and first editor was physician, poet, journalist, and political activist Sigurður Júlíus Jóhannesson, better known as Siggi Júl.

A typical issue of Sólskin contained a selection of poems, stories, short essays, biographical sketches, riddles, and games. Sólskin also often included letters sent to the paper by its young readers. Many letters originated locally in Manitoba, but others arrived from as far west as British Columbia, from several areas south of the border, and in rare cases even from Iceland.

Jorundur Eyford recalls how he learned to read Icelandic and the medical care Siggi Júl provided to his family. Enjoy this audio clip with an English transcript.

Julianna Hill recalls how she and her brother learned to read Icelandic. Enjoy this audio clip with an English transcript.

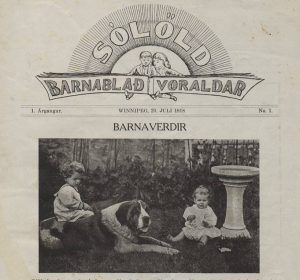

In 1918, Siggi Júl launched Sólöld, a new children’s periodical. It lasted just six months. However, in 1934, he launched Baldursbrá, a bi-weekly magazine that closely resembled Sólskin in its format and contents. Baldursbrá lasted for more than six years. Publications like these were crucial to migrant Icelanders’ efforts to preserve their language in North America among the younger generations.