The Icelanders Arrive

Between 1870 and 1914, more than 16,000 Icelanders, or roughly 20% of Iceland’s population, migrated to North America. Many different factors led the Icelanders to migrate. These factors include widespread poverty, an outbreak of sheep pestilence, the impact of the eruption of the volcano Askja in 1875, and several consecutive years of harsh weather. Icelanders were attracted to North America by the prospect of greater upward mobility and economic opportunities.

Arni Sigurdsson discusses the arrival of the first Icelandic migrants to New Iceland. Enjoy this video with an English transcript.

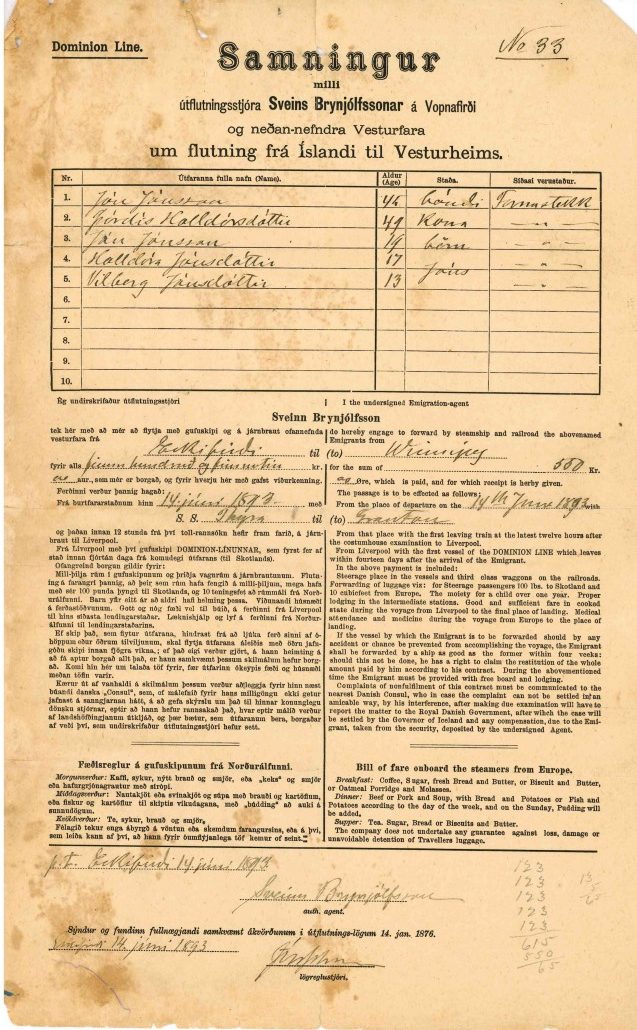

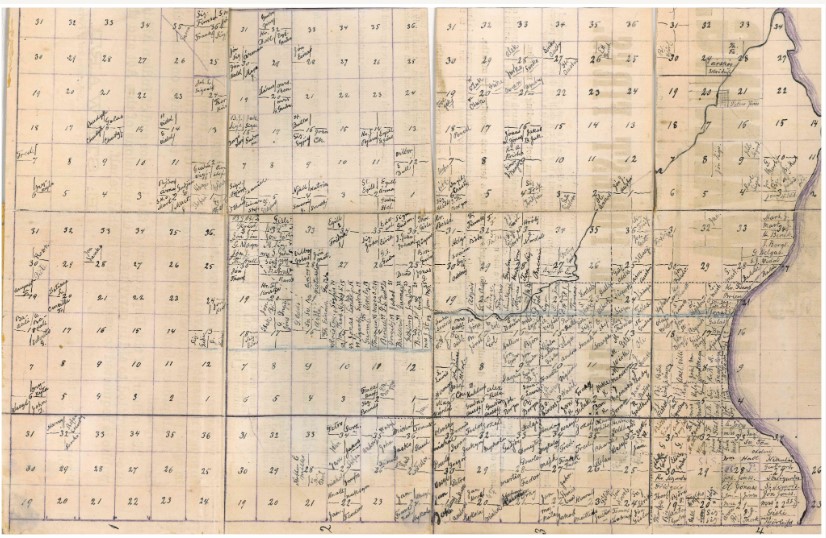

Migrant Icelanders crossed the North Atlantic by ship. They travelled across the land by rail or wagon and crossed lakes and rivers by steamboat. The earliest migrants settled in parts of Wisconsin, Nebraska, and Minnesota. North of the border, Icelanders settled in parts of Nova Scotia and Ontario before heading west. Eventually, parts of what later became the province of Manitoba attracted the highest numbers of Icelandic migrants.

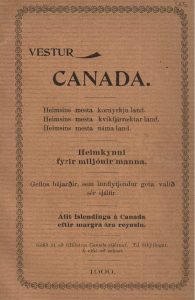

Canada sought to attract migrant Icelanders to the New Iceland Colony reserve with the promise of land and hopes of a better life. Populating the area with European migrants aided Canada’s ongoing efforts to expand the settler colonial state westward.

Salome Johnson describes her family’s journey from Iceland to North America. Enjoy this video with an English transcript.

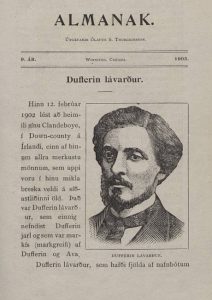

Canada’s Governor General, Lord Dufferin, visited New Iceland in 1877. He remarked that he had “not entered a single hut or cottage in the settlement which did not contain, no matter how bare its walls, or scanty its furniture, a library of twenty or thirty volumes.” Icelanders typically arrived with printed books or handwritten manuscripts in their travel trunks. In the past and still today, Icelandic identity is inseparable from Iceland’s literary traditions.

The migrants in New Iceland felt that to preserve their culture and language and to maintain a sense of Icelandic identity, the production of an Icelandic newspaper was vital. Despite poor living conditions and many early hardships, including a deadly smallpox outbreak, the New Icelanders were determined to achieve this goal.