27

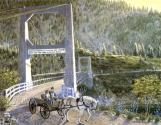

Suspended In Time1998

Brilliant, BC, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Painting by Michael M. Voykin of Shoreacres, BC, 1974

28

Aside from the sporadic but yet infrequent uprisings of the Sons of Freedom, the Doukhobors it seemed were once again in their 'Golden Years'. All operations were flourishing, the Valley of Consolation seemed to become the Valley of Prosperity and most were inclined to be satisfied with their peaceful way of communal life. The enterprises in Saskatchewan were thriving too with their own grain elevator, flour mill, brick factory, and other operations.Generally, there were a few that couldn't abide by the communal system that left on their own accord to become independent land owners or workers in BC, and there were those that were literally banished for not following the 'rules' of the community. But on the most part, the Doukhobors were at a relatively rare, peaceful and prosperous time in their lives.

29

The Verigin Community store1911

Verigin, Saskatchewan, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Self portrait of Russian photographer Alexandra Korcini

30

The Verigin store - a community run operation where most Doukhobors could pick up there supplies. Verigin, Sakatchewan, 1911. (The woman with the plume is Alexandra Korcini, photographer and friend of Tolstoy).32

Inside of the community brick works where steam powered a cable assembly to take bricks to outdoor drying kilns and then on to the storage buildings33

Community mill and elevator1911

Verigin, Saskatchewan, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Photo by Alexandra Korcini

From the Autochrome Exhibit, Doukhobor Village Museum, Castlegar, BC

34

The community elevator and flour mill in Verigin Sakatchewan, 1911.35

Alexandra Korcini at the Verigin Station1911

Verigin, Saskatchewan, Canada

Credits:

Credits:From the Autochrome Exhibit, Doukhobor Village Museum, Castlegar, BC

Self portrait of Russian photographer Alexandra Korcini

36

Clashes with the provincial government of British Columbia were not far off though, and in time, these clashes would inevitably contribute to the demise of the largest and most successful ever communal operations in North America. The immediate issues of concern to the provincial government were issues of education, taxation, and registration of births and deaths. The Doukhobors, who had been earlier told that the province wouldn't interfere with the business of the Doukhobors did not believe that public education was appropriate for them - not to say that they didn't believe in education - just not the type to which Doukhobor children would be submitted. (A seemingly simple thing like singing God save the King was religiously inappropriate - this refusal is common and accepted in today's schools, but at the time such an issue was unheard of). And in that era, education even in BC was based highly on a pre-para-military basis.Militia and rifle training was introduced in BC public schools which alienated the Doukhobors even more, and they boycotted public education in BC until 1915 when a compromise was reached and no paramilitary training would be forced upon the Doukhobor children. Verigin was very much cognizant of the importance of education and under his direction nine schools were subsequently built on CCUB owned land and some children even attended public schools. For those who wouldn't obey, fines were levied by the government and these became more preferred as it was a way of weakening the Community of its assets. For a time, school was not an issue; enrollment and attendance never equaled the Canadian average but it was the first time that Doukhobor children became literate in Canada.

37

On the issue of taxation, the CCUB did pay taxes and not unlike many people or corporations of today, there seemed to be a disagreement between government and the CCUB as a tax payer, as to what was payable. The members themselves didn't because they earned far below the earning level of exemption. But the government's public statement of taxation concerns seems not to be credible; if there were any concerns, it is highly unlikely that the government would have finally contributed to the building costs of the Brilliant Bridge.Registration of vital statistics was, for whatever reason, a sore point in the eyes of the Doukhobors. The local authorities, in an effort to 'bully' the Doukhobors into submission, reacted hastily and irresponsibly when they began arresting some Doukhobors and jailing them for not registering deaths. At the horror of the Doukhobors (and some of the general public), police even went to the extent of exhuming bodies in Grand Forks as proof of theses deaths. Obviously, none of these actions sanctioned by government were to be an example of trust of the authorities, and the Doukhobors were rightfully suspicious of this government, as they were of any other government during any time of their history.

38

It's interesting to note that prior to 1914, letters to the editor in the local newspapers (such as the Nelson Daily News) were mostly, if not entirely, supportive of the Doukhobors. They were referred to as hardworking, sober, quiet, and helpful and compassionate people.People even voiced their outrage that the government wouldn't contribute monies to help the Doukhobors build their road system, or even help with the building of the Brilliant Suspension Bridge (though by 1914, the government did finally contribute a total of $19,500 to the costs).

But positive compliments soon turned to criticism and resentment from their English-speaking neighbours at the outbreak of the first world war.

39

Other settlers, and those with vested interests in retail business, began to voice their disapproval of the self-sufficiency and the mass purchasing power of the Doukhobors.They argued that while the Doukhobors sold lumber products, agricultural produce and some dairy products, and bricks were now even available for purchase, the Doukhobors provided minimal business in return to local merchants. (It seemed that the locals who voiced these concerns had by this time forgotten that the jam factory continually purchased produce from local independent growers as well).

That, along with their status as conscientious objectors did not endear them to the locals - especially considering that the local English-speaking boys were fighting overseas with the prospect of losing life, limb, or both, while the pacifist Doukhobor stayed at home, only to prosper in peace.

40

While the provincial committee of the Patriot Fund demanded $75,000 from the CCUB for the war effort, Verigin approved only $10,000. After the war ended in 1919 and the fighting men returned, resentment towards the Doukhobors had probably reached an all time high.The community itself had its share of dissenters within as well. Not all within the community agreed with Verigin's ways.

And certainly from the outside, there was not only attack from the public, but the government of the Province of BC had their own gripes with the Doukhobor people.