1

PLAYING WITH FIRE!

In 1867, the first church of Batiscan was abandoned when a bigger church was built. The old building was then transformed into a match factory by Father Fréchette. Needless to say, this caused quite a scandal among the parishioners. The controversy was however short-lived; the factory burned down due to an accident, causing Father Fréchette to go bankrupt. That's what happens when one plays with fire...

In the first half of the 19th century, the piece of land where the old presbytery stood was at the heart of the activities of the Batiscan community. The church, the cemetery and the flour mill were located near the priest's residence. There were some problems, however, with the small church accommodating the needs of the expanding parish. It was decided that a bigger church and a new presbytery would be built further to the east, in the vicinity of the docks. The wharfs were then at the center of the village activities, a consequence of the boom in the regional forest exploitation and the arrival of schooners at the shipyards. Wenceslas Fréchette, who was then the parish priest, took on the costs of the construction of his new residence. In exchange for this, he received the abandoned church, the old presbytery and the adjoining buildings as a donation from the parishioners.

In 1875, Father Fréchette entered into a partnership with his nephews Léandre W.T Fréchet and Onézime Fréchette in order to set up a match factory. Father Fréchette contributed the building, the capital investment, as well as all the tools and equipment required. He entrusted the administration of the venture to one of his nephews.

2

Priest and businessman17 March 2008

Batiscan (Quebec), Canada

Credits:

Credits:Collaboration of Vox, Cap-de-la-Madeleine

3

Sulfur matches were a brand new invention at the time. This innovation brought on a certain degree of independence and revolutionized daily lifestyles. People could now easily light candles and lamps. Fréchette perceived this new product as having the potential for a very lucrative and appealing market.

4

Lighter and flint19th century, before 1860

Batiscan (Quebec), Canada

Credits:

Credits:Collection of the Musée de la civilisation

Archives of the Fondation des Amis du Vieux presbytère de Batiscan

5

Of course, such an undertaking had people talking. Imagine a priest implanting a factory in a church... No need to worry though, the steeple, the bell, the sacred objects, the candlesticks, the statues, the lamps and the high altar were all moved to the new church before the factory was up and running.

6

Figurine of St. Ignace of Loyola18th century, circa 1742

Batiscan (Quebec), Canada

Credits:

Credits:Collection of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec

7

Statue of St. Joseph18th century, circa 1734

Batiscan (Quebec), Canada

Credits:

Credits:Collection of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec

8

High altar of the second church18th century, circa 1741

Batiscan (Quebec), Canada

Credits:

Credits:Collection of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec

10

HOW ARE MATCHES MADE?

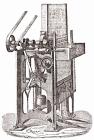

The wood - usually a soft essence such as aspen, poplar, birch or linden - is first cross-cut to a width equivalent to the length of a match. These pieces are dried in an oven and then fed into a special machine that cuts them into matches. A plane composed of 50 sharp dies moves back and forth and, depending on the shape of the dies, cuts out 50 round, square or fluted matches in the piece of wood.

11

Step 119th century, circa 1875

Batiscan (Quebec), Canada

Credits:

Credits:Archives of the Fondation des Amis du Vieux presbytère de Batiscan

12

Afterwards, the sticks are placed in wooden frames. These are then set in vertical presses and maintained at equal distance by a series of wooden strips. Once held in place in this way, the matches are dipped into a bath of sulfur and paraffin wax.

13

Step 219th century, circa 1875

Batiscan (Quebec), Canada

Credits:

Credits:Archives of the Fondation des Amis du Vieux presbytère de Batiscan

14

While still inserted in their wooden frame, the matches are dipped into a chemical paste. The paste is spread in a thin coat over a hot plate heated by a double-boiler to be maintained in a semi-liquid state. The wooden frame containing the sulfur impregnated matches is applied on the plate and each stick is coated with a few millimeters of paste.