2

The position had been taken, there was to be no turning back. When Lev Tolstoy and his associate, Vladimir Tchertkov, heard of the oppression of these peasants for their anti-military stand, they sprang into action. Tolstoy sent a colleague, Pavel Birukov, to the Caucasus to investigate the persecution. The results were published in an article called "The Persecution of Christians in Russia" in the London Times.Tolstoy also wrote about this in the Contemporary Review and the world soon learned of the plight of the Doukhobors. An early publication in 1897 called "Christian Martyrdom In Russia" was followed by other appeals and soon brought the attention of the world to the Doukhobors' plight. Publicity was generated throughout various countries and sympathy was generous.

3

Tolstoyans: Russians and other humanitarians who helped the Doukhobor plight14 October 2003

London, England

4

The Society of Friends, or the Quakers, as they were commonly known in England, protested the harsh treatment. As a result of the world wide publicity generated primarily by Tolstoy and Vladimir Tchertkov, the Russian autocracy could no longer ignore these people and regard the event as a simple, internal matter - a group of ignorant, dissident peasants to be merely starved and beaten into submission - or systematically and eventually obliterated for their religious beliefs.6

Ongoing correspondence between Lev Tolstoy and Peter Verigin of the time reveals that a lack of confidence existed that the Doukhobors would ever be able to maintain their religious attitudes and practice while in Russia.Simultaneously, the Russian authorities were now agreeable to releasing these dissidents who, for centuries, had caused nothing but problems for the Russian authorities. Russia now agreed to let the majority of them leave, if they paid for their own passage, and on condition that they would never be allowed to return.

7

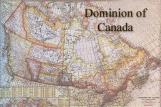

Tolstoy completed a novel that he had been working on and donated the proceeds of 'Resurrection' to aid in emigration expenses, and he also raised other money from his wealthy friends. Other donations were collected, (the Quakers being one of the largest financial contributors). Canada, hungering for settlers for the yet-to-be cultivated western prairies, agreed to accept the Doukhobors. It was apparent that they were skilled and hardworking knowledgeable farmers. The Dominion of Canada wanted the Doukhobors and negotiated with the 'Tolstoyans' who represented the Doukhobors' interests from a humanitarian standpoint.8

Desperate to leave quickly, without proper investigation, some of the Doukhobors were able to leave for Cyprus. Not being too far from the port of Batum, in terms of cost, it was bearable. By summer of 1897 the Quakers and Mennonites had raised enough for the first contingent of slightly over 1100 Doukhobors to leave. What the Doukhobors did not count on was that the climate was not hospitable, and nor was the soil for this agriculturally dependent sect. Malaria and dysentery were just some of the diseases that claimed over 10 percent of the Doukhobors that tried to make Cyprus home. The remainder left Cyprus quickly when the opportunity presented itself.10

These 'Tolstoyans' included Tolstoy himself and a few of his distinguished associates, Tchertkov, Birukov and Tregubov. (The latter three were themselves exiled for their efforts). The well known anarchist, Prince Peter Kropotkin, a veteran of Siberian exile had suggested the Canadian location. There were a few other choices at the time to where the Doukhobors could emigrate; Texas had been discussed, as was Hawaii, Brazil, Argentina, Georgia, and even China. James Mavor, a professor at the University of Toronto, corresponded with the Tolstoyans. Mavor in turn began negotiations with the Minister of Interior, Clifford Sifton, and through Sifton, the Dominion of Canada agreed to the Doukhobors' requests.12

New BeginningsIn 1898 an agreement was reached with the Dominion of Canada which guaranteed the simple conditions the Doukhobors requested: they were not to be required to perform military service, they could farm their land communally with land held in common or 'en bloc', and they would retain control of the internal affairs of their villages.

The 'conscientious objector status' given was the same as the Quakers, Tunkers, and Mennonites had been earlier granted - meaning if war ever broke, the Doukhobors would have the right to refuse to fight or bear arms by reason of their religion. The Doukhobors were advised however, that they would have to live according to the 'laws of the land' but were not advised that those laws might require them to swear an oath of allegiance - something the Doukhobors were not inclined to do.

14

After a long voyage that started on December 21st, 1898, the first contingent of 2,134 Doukhobors arrived in Halifax, Canada, which then proceeded to St. John, New Brunswick on January 24th 1899. Ten Doukhobors died en route, but with spirits high and hopeful, they were greeted by Quakers, newspaper reporters, James Smart, the deputy minister of the interior and other distinguished onlookers. All were duly impressed with the health of the Doukhobors, their behaviour, their singing, and the cleanliness of their ship (which they had fastidiously maintained and cleaned during the month-plus voyage).The S.S. Lake Huron then sailed to St. John where this group would take five trains to western Canada. (Some passengers of the S.S. Lake Huron were to remain in quarantine in Halifax).