1

Logs piled at the mill20th Century, Circa 1923

The West Country, west of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Stelfox, Henry: "Rambling Thoughts of a Wandering Fellow"

2

Henry Stelfox tried to make a living for himself and his family in the early 1920's by setting up his own lumber camp in the Rocky Mountain House area, as a contractor delivering logs to a sawmill. Henry was in charge of the fallers, skidders, and teamsters he hired to take the logs out, and had a bookkeeper to measure (scale) the logs as they were loaded onto the sleighs to be taken down to the frozen North Saskatchewan River, and hauled to the sawmill. The sawmill manager told Henry that his logs would be scaled at their hot pond (the logs cannot be sawed until thawed, because the sap in the outer three inches of spruce logs would be frozen in winter and very slippery, like glass, and unpredictable). Henry agreed that this would be acceptable. But near the end of the season, one of his teamsters told Henry that most of his logs weren't being scaled before being dumped into the hot pond, and Henry then asked the manager of the sawmill for an explanation. Because the company bookkeeper had only scaled one-quarter of the logs Henry's teamsters delivered, the company made an offer to pay Henry for the average of his loads that had been scaled. This really worked in the company's favour, and Henry was forced to sell his assets to pay his camp staff. When Henry threatened legal action, it was discovered that his own bookkeeper had disappeared, and so had the company's bookkeeper.To earn a living for his family, which at this point included his wife Janet, and five children, Henry loaded railway ties into boxcars a mile west of Rocky Mountain House, which was very hard work. He then heard from a friend in the Lacombe area that the Rawleigh Patent Home Medicine Company needed an agent in the Rocky Mountain House area, so Henry signed up to sell the Rawleigh goods, and he traveled to the coal mining centers of Saunders, Alexo, and Nordegg to make sales. He earned enough money doing this to put a downpayment on a livery barn in Rocky Mountain House. Henry also took over the job of auctioneer's clerk, and supplied butchered beef to some of the logging camps and saw mills in the area.

3

Cree Indians at the Baptiste River20th Century, Circa 1930

Baptiste River, West of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Henry Stelfox

4

Cabin at the Baptiste River settlement20th Century, Circa 1935

Baptiste River, West of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Unknown

5

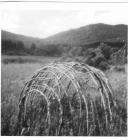

Frame for a sweat lodge20th Century, Circa 1930

Baptiste River, West of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Henry Stelfox

6

Unknown Indian woman with horse20th Century, Circa 1935

The West Country, west of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Mrs. Glenn

7

One of Henry's most successful business enterprises was that of fur buyer. His yearly fur buying license allowed him to purchase stretched pelts from white and Indian trappers, and he recalls in one evening buying 6,000 squirrel hides, along with a few coyote, muskrat and weasel pelts from five Chippewa Indians from the Nordegg River. If Henry wasn't in his office, the First Nations' people knew that they could find him at home, and quite often, in wintertime, these friends slept on the floor overnight at his home. (Henry and Janet's house had been Rocky Mountain House's first schoolhouse, and the classroom was converted into the dining room.) The guests would keep the night fire going and the eldest Stelfox girls would make breakfast for two separate sittings for the First Nations' women. If his Indian friends stopped in at the office in late afternoon, Henry would always invite them to stay overnight. One winter morning Henry went to the office and counted seventeen people sleeping on the floor.Henry Stelfox fell in love with Alberta's natural beauty and abundance when he first came to Alberta. His friend Chief Yellowface would tell Henry stories of how the Chippewa people thrived in Alberta, with its many blessings; the buffalo, the moose, elk, deer, and waterfowl. Henry wrote down as much of the oral history as was related to him. Mrs. Bessie Swan, and Joseph Lagrelle, along with Chief Yellowface, and Chief Jim O'Chiese shared with Henry what they could about the travels of the various tribes in Alberta, from the O'Chiese Chippewa's migration north of the North Saskatchewan River after the great fires of 1867, to the travels and trading customs of the Blackfeet, Chippewa, Kootenai, Shushwap, Peigan, Cree and Stoney both before contact with the white man and after contact. Henry learned about his friends ancestors, and was amazed by the tales of buffalo hunts, and the story of the birth of Jim O'Chiese's father, Ha-Ka-ma-sen, at the Big Rock (now within the town limits of Rocky Mountain House) in 1790. (The band of Chippewa was on the move from their winter headquarters at the Baptiste and Nordegg Rivers, and crossed over the flooding North Saskatchewan River. The chief's wife, Jim O'Chiese's grandmother, was due to give birth. She did give birth just after crossing the river on horseback, but she nearly drowned in the river. Ha-Ka-ma-sen translates as "The Other Side of the Rock".)

8

Chief Louis Sunchild (Cree) signing treaty May 25, 194425 May 1944

Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Unknown

9

Chief Louis Sunchild in front of the Stelfox home20th Century, Circa 1944

Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Stelfox, Henry

10

Henry Stelfox explaining that beavers must not be exterminated20th Century, Circa 1945

The West Country, west of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Unknown

11

Chief Louis Sunchild and Mr. and Mrs. Mike Frencheater20th Century, Circa 1949

Sunchild Cree Reservation, Baptiste River, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Unknown

12

Henry Stelfox and some members of the Sunchild Cree Band20th Century, Circa 1945

The West Country, west of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Unknown

13

Chief Walking Buffalo and Chief David Crowchild in South Africa20th Century, Circa 1960

South Africa

Credits:

Credits:Unknown

14

The Chippewa band who lived around the Babtiste and Nordegg Rivers prided themselves on being self-sufficient. Once the buffalo were gone, the members of this band would hire themselves out to the farmers of the Rocky Mountain House district, and help clear brush in the spring and help with harvest in the fall of the year. But there was little work for the Chippewa band members in the summer and fall of 1931. Henry Stelfox could see plainly that his Indian friends were close to starving, as they couldn't pay for any food from the merchants in Rocky Mountain House. The Department of Indian Affairs was informed of the 'very lean times the O'Chiese band of Chippewas were experiencing' and a shipment of clothing and food arrived in late December of 1931. Henry enlisted the help of his brother Tom to load a triple wagon box sleigh and hitch up a very strong team to head out across the snow-covered trail and frozen muskeg to reach the Chippewa's winter encampment. It was 35 degrees below zero (equal to minus 37 Celcius) and with a foot of snow on the ground, the trip would take them three days, as there were no proper roads in that district to take them out to the Nordegg River. One part of the trail was through a canyon, and the trail wasn't level, and try as they might to balance the load by standing on the uphill side of the wagon, Tom and Henry didn't weigh enough to to keep the load from upsetting. It took them quite a bit of work to move all of the boxes out of the way before they could right the sleigh and sleighbox and reload the boxes. As they continued through the canyon, the load upset five times. When they arrived at the Chippewa village, Henry and Tom set up their own tent, and had supper. After supper, Henry saw his old friend Yellowface emerge from his tepee. Henry could see that Yellowface was saying his evening prayers. After waiting a few moments, Henry greeted Yellowface, and told him the purpose of their visit. Yellowface returned to his own tepee, and then Yellowface's cousin came to see Henry. The cousin told Henry that they would not accept any food or clothing from the government, and that the items were not to be left in the village. Two more representatives came to Henry's tent and told him that they did not want any of the items that Henry had brought. After working so hard to deliver the warm clothing and boxes of sugar and tea, and flour, it must have been a head-shaking moment for Henry. When Yellowface returned to see Henry later that evening, he asked what the men who had visited Henry had to say, and so Henry related that Yellowface's cousin gave the word that no one was to accept any of the goods from the government. Yellowface said that he wouldn't go against the wishes of his people on the matter, (it was a delicate line that Yellowface walked, as his uncle Chief Jim O'Chiese had passed away only a month previous). Yellowface wished Henry to convey his gratefulness for the Director of Indian Affairs thoughtfulness in sending food and clothing.Yellowface invited Henry and his brother to attend the Christmas feast that evening. Henry said he would be pleased, and that he wished to give Yellowface a gift from his own house, including tobacco, bacon, cookies, bread, butter, lard, and apples, oranges and nuts. Yellowface gladly accepted the gifts that came from Henry personally, and the three men proceeded to the assembly hall for the feast later that evening. The ceremonial pipe was lit and passed around, speeches were made, and then the feast began.

Henry and Tom returned to Rocky Mountain House, but avoided the canyon that had caused so much trouble for them on the way in. In the New Year, Henry was able to divide the shipment into smaller parcels, and when individuals from the O'Chiese Chippewas would visit Henry in town, Henry would present them with a gift, saying only that a friend had sent it. It took Henry most of the year, but all of the food and clothing finally made it to the people first intended.